2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize Winner

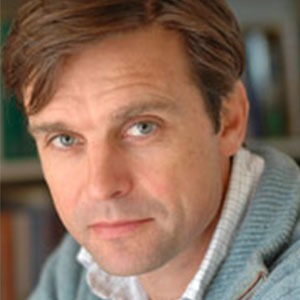

Michael Redhill

Bellevue Square

2017 Shortlist

The 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its shortlist on Monday, October 2, 2017. The shortlist was revealed at the Scotiabank Centre in Toronto before more than 100 media and members of the publishing industry gathered for the unveiling at a special event hosted by CBC Radio’s Gill Deacon.

Transit by Rachel Cusk

Biography

Rachel Cusk is the author of three memoirs – A Life’s Work, The Last Supper and Aftermath – and her novels include – Saving Agnes, winner of the Whitbread First Novel Award; The Temporary; The Country Life, which won a Somerset Maugham Award; The Lucky Ones; In the Fold; Arlington Park; and The Bradshaw Variations. She was named among Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2003. Her novel Outline was a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2015. She lives in London.

Jury Citation

In Transit, Rachel Cusk’s elegant, witty and brilliantly realized novel, Faye, a writer, moves to London with her young sons and purchases a dilapidated apartment. On this deceptively simple scaffolding, Cusk constructs a series of finely observed and complex stories about people whose paths intersect with the narrator’s. The result is a book which is simultaneously intimate and expansive, alight with wisdom and humour, an exquisitely poised meditation on life, time, and change.

Minds of Winter by Ed O'Loughlin

Biography

Ed O’Loughlin is an Irish-Canadian author and journalist. His first novel, Not Untrue and Not Unkind, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2009 and shortlisted for the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Award. His second novel, Toploader, was published in 2011. As a journalist, Ed reported from Africa for several papers, including the Irish Times. He was the Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age of Melbourne. Ed was born in Toronto and raised in Ireland. He now lives in Dublin with

Jury Citation

Bright moments from the distant past spring up beside dark moments from the present, things hidden – a death, a gift, a lost clock – come briefly into view and then disappear forever. In Minds of Winter, Ed O’Loughlin’s brilliant story of polar exploration, time itself is an Arctic: a mysterious dimension of sun craze and apparitions, chance encounters and destiny. The mechanism of this novel is fascinating to observe, its implications are deeply human. In O’Loughlin’s work, our desire for knowledge, our obsession with the past, our grappling with life itself … all of it is generously, wittily on display.

Bellevue Square by Michael Redhill

Biography

Michael Redhill is a novelist, poet, playwright and former publisher of Brick. He is the author of the novels Bellevue Square, Consolation and Martin Sloane, which was a finalist for the 2001 Giller Prize; the short story collection Fidelity; and the poetry collection Light-Crossing; among other acclaimed works. He lives in Toronto, Ontario.

Jury Citation

To borrow a line from Michael Redhill’s beautiful Bellevue Square, “I do subtlety in other areas of my life.” So let’s look past the complex literary wonders of this book, the doppelgangers and bifurcated brains and alternate selves, the explorations of family, community, mental health, and literary life. Let’s stay straightforward, and tell you that beyond the mysterious elements, this novel is warm, and funny, and smart. Let’s celebrate that it is, simply, a pleasure to read.

Son of a Trickster by Eden Robinson

Biography

Haisla/Heiltsuk novelist Eden Robinson is the author of a collection of short stories written when she was a Goth called Traplines, which won the Winifred Holtby Prize in the UK. Her two previous novels, Monkey Beach and Blood Sports, were written before she discovered she was gluten-intolerant and tend to be quite grim, the latter being especially gruesome because half-way through writing the manuscript, Robinson gave up a two-pack a day cigarette habit and the more she suffered, the more her characters suffered. Monkey Beach won the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and was a finalist for the Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award for Fiction. Son of a Trickster was written under the influence of pan-fried tofu and nutritional yeast, which may explain things but probably doesn’t. The author lives in Kitimat, BC.

Jury Citation

Eden Robinson’s Son of a Trickster is a novel that shimmers with magic and vitality, featuring a compelling narrator, somewhere between Holden Caulfield and Harry Potter. Just when you think Jared’s teenage journey couldn’t be more grounded in gritty, grinding reality, his addled perceptions take us into a realm beyond his small-town life, somewhere both seductive and dangerous. Energetic, often darkly funny, sometimes poignant, this is a book that will resonate long after the reader has devoured the final page.

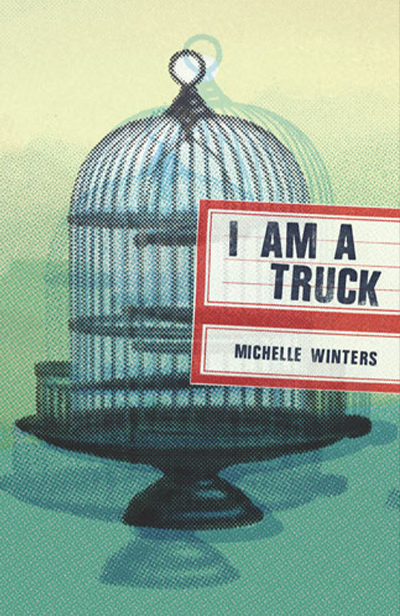

I Am A Truck by Michelle Winters

Biography

Michelle Winters is a writer, painter, and translator from Saint John, NB. She was nominated for the 2011 Journey Prize and her work has been published in This Magazine, Dragnet and Taddle Creek. She is the co-translator of My Planet of Kites, by Marie-Ève Comtois. She lives in Toronto.

Jury Citation

French or English, stick or twist, Chevy or Ford? Michelle Winters has written an original, off-beat novel that explores the gaps between what people are and what they want to be. For a short book I am a Truck is bursting with huge appetites, for love and le rock-and-roll and cheese, for male friendship and takeout tea with the bag left in. Within the novel’s distinctive Acadian setting French and English co-exist like old friends – comfortable, supple to each other’s whims and rhythms, sometimes bickering but always contributing to this fine, very funny, fully-achieved novel about connection and misunderstanding. And trucks.

2017 Longlist

The 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its longlist on Monday, September 18, 2017.

Brother by David Chariandy

A great lookout, my brother told me. One of the best in the neighbourhood, but step badly on a line, touch your hand to the wrong metal part while you’re brushing up against another, and you’d burn. Hang scarecrow-stiff and smoking in the air, dead black sight for all. “You want to go out like that?” he asked. So when you climbed, he said, you had to go careful. You had to watch your older brother and follow close his moves. You had to think back on every step before you took it. Remembering hard the whole way up.

He taught me that, my older brother. Memory’s got nothing to do with the old and grey and faraway gone. Memory’s the muscle sting of now. A kid reaching brave in the skull hum of power.

“And if you can’t memory right,” he said, “you lose.”

ONE

She’s come back. The bus pulling away from a rotting bank of snow to show her standing on the other side of the avenue. A neighbourhood girl no longer, a young woman now in heeled boots and a coat belted tight against the cold and dark. She’s carrying a backpack, not a suitcase, and this really is how she becomes Aisha. The way she shoulders her belongings with a rough and impatient gesture before stepping onto the asphalt and crossing the salt-stained lanes between us.

“You’re not dressed for this weather,” she says.

“I’m okay. Just a short wait. You look good, Aisha.”

She frowns but accepts from me a hug that lingers before we break apart and begin walking eastward, our chins hunched down against the wind tunnelling between the surrounding apartment towers. An oncoming car shocks bright her face and it’s true, she does look good. The same dark skin haunted with red, the same hair she once scorned as “mongrel.” But it’s been ten years since last we’ve spoken. And in the silence thick between us it feels like even the smallest dishonesty will ruin this reconnection. A truck blasts suddenly past us on the avenue, spraying slush on our pant legs and shoes. Aisha swears, but when our eyes meet she offers a thin smile.

“Properly welcomed back,” she says.

“You do look a bit tired. I’ve made a bed for you.”

“Thank you, Michael. Thank you for offering me a place to stay. I’m sorry for not saying so sooner. My head these days. And you know me, I’ve never been good with favours.”

She was overseas when she got the news that her father had been admitted into intensive care, and during her phone call to me she described how her mind instantly filled with panic but also vague anger. In his occasional letters to her, he had mentioned that he was feeling tired, but he had not admitted the cancer. She caught a long series of connecting flights to Toronto, and then Greyhound bus to the hospice in Milton, the small town he had moved to only recently. She stayed with him for the week until the end, and there had been time to talk but not nearly enough. “What was there to say?” she asked me in a rough voice over the phone, the line hanging afterwards with a quiet impossible for me to fill. This call out of nowhere. “Please visit,” I said to her, doubt creeping into my voice even as I repeated myself. “Come home to the Park.”

The Park is all of this surrounding us. This cluster of low-rises and townhomes and leaning concrete apartment towers set tonight against a sky dull purple with the wasted light of a city. We are approaching the western edge of the Lawrence Avenue bridge, a monster of reinforced concrete over two hundred yards in length. Hundreds of feet beneath it runs the Rouge Valley, cutting its own way through the suburb, heedless of manmade grids. But the Rouge is invisible to us tonight, and we have just arrived at the Waldorf, a townhouse complex at the edge of the bridge and made of crumbling salmon brick, flapping blue tarps draped eternally over its northeast corner. The unit where Aisha lived ten years ago with her father is on the prized south of the building, away from traffic. But the side where I have remained all my life is at the busy edge of the avenue, exposed to the constant hiss of tires on asphalt. I warn Aisha about the loose concrete on the doorsteps and suffer a sudden bout of clumsiness working the brass key into the lock. I push open the door to show a living room lit blue with the shifting light of a television, its volume turned off. There is a couch with its back towards us, and on it there is a woman with greying hair who does not turn.

I gesture to Aisha that we should be quiet. I remove my shoes in a demonstrating way, and with our coats still on I quickly guide Aisha across the living room. The woman on the couch continues to watch the silent television, the mime of a talk-show interview, a celebrity guest throwing his head back in laughter. I lead Aisha down a short hallway to the second bedroom. A small lamp casting a circle of light upon a desk, a bunk bed with a mattress and sheets on the lower bed only, the upper bunk long ago stripped bare, even the mattress removed, leaving skeletal slats of wood. I close the door behind us and in the sudden smallness of the room begin explaining. We won’t be sleeping together on the bed, of course. I’ll be using the living room couch, which is quite comfortable, honestly. I point out the towel and extra blankets set out very obviously on the sheets of the lower bunk. I stop when I notice that Aisha is staring and that she hasn’t let her backpack touch the floor.

“Your mother doesn’t speak anymore?” she asks.

“She speaks. She’s just quiet sometimes, especially at night.”

“I’m sorry,” she says to me, shaking her head. “I shouldn’t have come. This is an intrusion.”

Bullets of slush smattering upon the bedroom window. Another truck that has passed too close to the curb outside. But in the wake of sudden noise, a feeling creeps upon me, one of shame, maybe, for imagining that I could try to end our conversation tonight like this. With talk of sleeping arrangements and towels. With acknowledgement of Aisha’s father, yet no acknowledgement of that other loss shadowing this room and measured in the ten years of silence between us.

“I still think of Francis,” she says.

—

Excerpted from BROTHER. Copyright © 2017 by David Chariandy. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Transit by Rachel Cusk

An astrologer emailed me to say she had important news for me concerning events in my immediate future. She could see things that I could not: my personal details had come into her possession and had allowed her to study the planets for their information. She wished me to know that a major transit was due to occur shortly in my sky. This information was causing her great excitement when she considered the changes it might represent. For a small fee she would share it with me and enable me to turn it to my advantage.

She could sense – the email continued – that I had lost my way in life, that I sometimes struggled to find meaning in my present circumstances and to feel hope for what was to come; she felt a strong personal connection between us, and while she couldn’t explain the feeling, she knew too that some things ought to defy explanation. She understood that many people closed their minds to the meaning of the sky above their heads, but she firmly believed I was not one of those people. I did not have the blind belief in reality that made others ask for concrete explanations. She knew that I had suffered sufficiently to begin asking certain questions, to which as yet I had received no reply. But the movements of the planets represented a zone of infinite reverberation to human destiny: perhaps it was simply that some people could not believe they were important enough to figure there. The sad fact, she said, is that in this era of science and unbelief we have lost the sense of our own significance. We have become cruel, to ourselves and others, because we believe that ultimately we have no value. What the planets offer, she said, is nothing less than the chance to regain faith in the grandeur of the human: how much more dignity and honour, how much kindness and responsibility and respect, would we bring to our dealings with one another if we believed that each and every one of us had a cosmic importance? She felt that I of all people could see the implications here for improvements in world peace and prosperity, not to mention the revolution an enhanced concept of fate could bring about in the personal side of things. She hoped I would forgive her for contacting me in this way and for speaking so openly. As she had already said, she felt a strong personal connection between us that had encouraged her to say what was in her heart.

It seemed possible that the same computer algorithms that had generated this email had also generated the astrologer herself: her phrases were too characterful, and the note of character was repeated too often; she was too obviously based on a human type to be, herself, human. As a result her sympathy and concern were slightly sinister; yet for those same reasons they also seemed impartial. A friend of mine, depressed in the wake of his divorce, had recently admitted that he often felt moved to tears by the concern for his health and well-being expressed in the phraseology of adverts and food packaging, and by the automated voices on trains and buses, apparently anxious that he might miss his stop; he actually felt something akin to love, he said, for the female voice that guided him while he was driving his car, so much more devotedly than his wife ever had. There has been a great harvest, he said, of language and information from life, and it may have become the case that the faux-human was growing more substantial and more relational than the original, that there was more tenderness to be had from a machine than from one’s fellow man. After all, the mechanised interface was the distillation not of one human but of many. Many astrologers had had to live, in other words, for this one example to have been created. What was soothing, he believed, was the very fact that this oceanic chorus was affixed in no one person, that it seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere: he recognised that a lot of people found this idea maddening, but for him the erosion of individuality was also the erosion of the power to hurt.

It was this same friend – a writer – who had advised me, back in the spring, that if I was moving to London with limited funds, it was better to buy a bad house in a good street than a good house somewhere bad. Only the very lucky and the very unlucky, he said, get an unmixed fate: the rest of us have to choose. The estate agent had been surprised that I adhered to this piece of wisdom, if wisdom it was. In his experience, he said, creative people valued the advantages of light and space over those of location. They tended to look for the potential in things, where most people sought the safety of conformity, of what had already been realised to the maximum, properties whose allure was merely the sum of exhausted possibilities, to which nothing further could be added. The irony, he said, was that such people, while afraid of being original, were also obsessed with originality. His clients went into ecstasies over the merest hint of a period feature: well, move out of the centre a little and you could have those in abundance for a fraction of the cost. It was a mystery to him, he said, why people continued to buy in over-inflated parts of the city when there were bargains to be had in up-and-coming areas. He supposed at the heart of it was their lack of imagination. Currently we were at the top of the market, he said: this situation, far from discouraging buyers, seemed actually to inflame them. He was witnessing scenes of outright pandemonium on a daily basis, his office stampeded with people elbowing one another aside to pay too much for too little as though their lives depended on it. He had conducted viewings where fights had broken out, presided over bidding wars of unprecedented aggression, had even been offered bribes for preferential treatment; all, he said, for properties that, looked at in the cold light of day, were unexceptional. What was striking was the genuine desperation of these people, once they were in the throes of desire: they would phone him hourly for updates, or call in at the office for no reason; they begged, and sometimes even wept; they were angry one minute and penitent the next, often regaling him with long confessions concerning their personal circumstances. He would have pitied them, were it not for the fact that they invariably erased the drama from their minds the instant it was over and the purchase completed, shedding not only the memory of their own conduct but also of the people who had had to put up with it.

—

Excerpted from TRANSIT. Copyright © 2017 by Rachel Cusk. Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

The Bone Mother by David Demchuk

Shortly after, we received the notice, and Sergyi left our farm to work at the thimble factory, as our father had when we were very small. Seventeen months later, Sergyi fell ill from pneumonia and died. The car from the factory arrived to take us to the funeral, but Mother refused to go. She instead asked that we hold a remembrance in town. The factory could not deny us this, but of course would not provide the body. He would be buried in the small graveyard just outside the factory gates. No matter. We held our own memorial. Our mother sat with me at the service, an arm’s length from where Sergyi and I had stood before the priest.

She reached over and squeezed my hand. “You may pass slowly through a valley dark and drenched with tears, but you must not rest there,” she said. “These things happen.”

Within two days, I received word from the thimble factory that I was to come and fulfill Sergyi’s five-year contract, which had three years and seven months remaining. This dismayed my mother, who would be left to tend our farm with her aged sister, whose entire being had curled into the shape of a claw. But it was an inevitability. My mother pleaded with me to stay with the farm, and offered to send herself in my place. This would not be accepted, as we both knew. The work was difficult and arduous, and unsuited to an elderly woman. I offered to send her money to hire a hand but she refused. She would have no other me on the farm but me.

We sat and ate our supper, a pale broth of cabbage and potato with scattered shreds of mutton drifting through it. I feared the meal would be our last together. The next morning, letter in one hand, a pasteboard valise in the other, I hired a driver to take me out into the countryside and up to the factory gate.

While the Grazyn Porcelain Factory also produced fine china for homes, hotels, and restaurants, near and far, it was celebrated the world over — as we in the village were frequently told — for the exquisite porcelain thimbles that had been manufactured for centuries using closely-guarded techniques developed by the Grazyn family. Every tsaritsa since Anastasia Romanovna had received a priceless Grazyn thimble as part of her wedding dowry. The factory produced only three hundred and thirty thimbles a year, each painstakingly formed from a special paste, then glazed and fired by hand. The workers lived there, ate there, slept there, for the duration of their contracts, and were then sent home with lifelong pensions — enough to clothe and house and feed their now-estranged families.

I realized as I rang the bell that I had known many such workers over the years, but that none had ever spoken of their time there. Even our father was silent on the matter, and we learned early on not to raise the subject.

After a moment, the door opened, and I was ushered inside. My belongings were taken from me, and I was led to a locker room where I was handed a pair of grey overalls, a fine-fitting pair of lambskin gloves, a kerchief for my hair and a cotton mask for my face. I changed and was taken to the factory floor, given a curt cursory tour of the front of the factory, where the thimbles emerged from the kiln, ready to be glazed and fired. Then, wordlessly, I was taken into the back of the factory. It was filled with boxes and crates and bins of human bones, boiled and scrubbed and gleaming.

Across the room, two men shovelled the bones into a huge metal grinder where giant stone burrs crushed them into coarse powder. The powder was sent through a series of furnaces, sifted and combed and ground between each, until what emerged at the end was a trickle of fine white ash.

The Grazyn family had provided our livestock and produce, chosen our grains, paid for our doctors and medicine, built and repaired our housing. They had given us our schooling, our training, our church, our cemetery. And not just for our village, but two others besides.

We all had been raised and fed and nurtured to become these bones.

“Sergyi was with the shovellers,” my guide said to me in a dry, distant voice. “We need three, or we fall behind. You must take his post. Can you do the job?”

“I can,” I said. I reached for the shovel hanging on a nearby hook — his shovel, I realized — and took my station, and went to work.

—

Excerpted from THE BONE MOTHER. Copyright © 2017 by David Demchuk. Published by ChiZine Publications. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

We'll All Be Burnt in Our Beds Some Nights by Joel Thomas Hynes

Come on, whatcha doing? How are ya? Poor Johnny. Touchy Johnny. In this mindset. How you are? Imagine. How’s our John-John doing? How’s he makin out, comin along, doing for himself? How’s he keepin? Fuck. Slung halfways out the window for a haul, cause that’s what this piss-arsed place is come to. Imagine that, tumbling out onto the street for the sake of a stale Number 7 cause where he might pollute his own room. Where he sleeps alone. Poor old Johnny. The vinyl sill busted and gouging into his ribcage. Oh yeah, Johnny could very well settle out on the front step, but that means back and forth the stairs every time and then sat out there, watchin the street … the temptation is too much now aint it? Might get foolish. Might wander off.

Buddy from next door takes his garbage out for tomorrow morning.

How together he is, how on top of it all he must be, hey Johnny? Then he sees a splotch of birdshit on his rig and dont he go over and polish it off with his sleeve! Rather have diseased pigeon shit on the clothes he’s wearing than on the rig he drives. Pigeon shit. That’s what’s in his head too. All their heads. Dont bother askin Johnny what’s going on around him. Who’s screwing who. What the fuck is going on. Carry on little mouse, carry on.

Good night, buddy goes. Good night.

He makes for his door then.

What? What? Johnny shouts down. What did you just say to me? What?

He looks up at Johnny then. Looks right at old John-John, that’s what he does. Looks right fucken at me. You cant fathom the gall.

Excuse me, buddy goes, what?

Right grand about it. Like first he’s tryna be all macho-cool and casual about it, the man, taking out the garbage. But soon as he’s called on it, soon as he’s brought to task, he’s rattled to the core and so instinct kicks in and he figures he might as well pretend he’s better and better off and better for it by tossing in some kinda upper-crust turn of phrase. But our John-John’s on it, dont even bother.

Excuse me, buddy goes.

His hand is on the knob and Johnny can tell buddy thinks he knows a thing or two about the likes of fellas like Johnny, hanging out his window with the splintered vinyl gouging into his liver, lookin like he’s waiting for the fire department to come rescue him. But Johnny dont need no rescuing tonight, no not tonight. He can think of a few that do. But not Johnny, not tonight. But buddy might, yes, he might need a rescuing. Buddy might need the jaws of life to separate him from the sidewalk before all the good nights are said and done this night.

Excuse me?

You heard me, I said what? What did you just say to me?

I said good night.

Why, Johnny goes, what for? What’s my night got to do with yours?

I said good night, buddy goes, I was being friendly. We’re neighbours.

Well now Johnny, fancy that. Being friendly. Friendly neighbours. What’s the score little man? Dont know do ya? Ask him Johnny. Betcha he dont know. Playing the role, that’s all. Role-playing. Dress rehearsal, all of it.

You wait right there, Johnny goes, you wait right there.

What? Why?

Cause I’m coming down. I wants to have a little chat with you.

No thanks, he goes, no thanks.

And then buddy’s away off into his house and the door latches behind him right quick. Hear how quick he latched that door? All scruffy rough and tumble with the birdshit on his sleeve and the hefty black boots with a dollar’s worth of steel peeking through the right toe. He looks the part alright, he looks the part. But is he? That’s always the grey zone. That’s always the part you have to crack open. Is he the part or simply tryna look the part? Man or mouse? Mouse or man? Johnny slings the butt end at the back of buddy’s rig and it hits it dead-on the back window and a shower of sparks floats to the ground and one settles into a puddle of grease or oil and stays glowing for a bit and Johnny’s hoping, hoping, praying that something catches fire and blows everything to goddamn smithereens. That lovely rig up in flames, the bonnet landing up near Tulk’s somewhere, bumper all aflame and rocketing in through the windshield of the car behind and then that bastard catching and blowing to bits, burning shrapnel flying into the shanty houses, a scorching fender right in on the kitchen table, right smack flame-smashing mad in the middle of the late-night decaf tea-party chatter and then the widespread panic with the howlin scramble for children and computers and photo albums and dogs and hamsters and these fucken little tarpaper shacks all leant one into the other burning and tumbling right down over the hill into the harbour. And Johnny knows, better than any man out there, Johnny knows that harbour’s gonna catch what with five hundred years of toxic venomous scum and poisonous chemical slop gurgling and spluttering, seething a hundred fathoms deep. You knows there’s something flammable about all that, something explosive. Burn burn burn. Right to the ground, right to the bottom of the harbour. Burn the works. And Johnny with it. Yeah. Cause they can batter to fuck this time around if they thinks Johnny’s going kickin flaming doors in again and crawling around lookin to save grizzled old farts who could very well drop dead tomorrow anyhow. Fucken Charlie, Christ.

Johnny hears buddy mumbling something down there.

Through the walls. Cause that’s the way, that’s the way they got us all jammed in. So we can all hear each other belching and farting through the goddamn walls. Tarpaper shacks with big bloated price tags, all slapped together and clung to the side of the cliff like gulls huddling, cluster-fucked. Waiting. You wouldnt even wanna know the state of this dive Johnny’s set up in. One of old Quinn’s spots and the welfare pays Quinn a fortune to let it rot and crumble around the likes of Johnny, fellas like that. The bad guys.

Mumble mumble down there. Some sorta big talk to his wife or his girlfriend. An oath, a curse. Talkin about Johnny, gotta be. Big talk, nothing he’d say to Johnny’s face. Role-playing. Shag this. Johnny’s down the stairs and out the front hall to the door. He dont even bother to put the sneakers on cause he’s not gonna be using his feet. You gotta be able to dance, dance, dance whenever the mood takes you. That’s the rule, that’s the law. Johnny gives the knuckles a good scrape across the panelling in the porch before he opens the door. Sting and burn, bleed, come on bleed. Clench and release, clench and release. Buddy started it didnt he? Good night, he says. Johnny’s night. Good. Johnny raps on buddy’s door. It’s a new door with a big patterned window to let the light in. Must be nice, letting all that light in. Must be nice to have it all lined up, new doors, taking the garbage out.

Someone passes up the street behind Johnny. It’s one of Shiner’s girls. Lookin no worse for the wear, gotta say. Gotta say. She looks to be jonesing for a little soul food, no question. But she got that sturdy scuff about herself, that kinda dont-fuck-with-me baygirl stride. Sneakers and jeans. Busy busy. There’ll always be money in love, like the fella says. Lotsa burdens needing a lift, egos stroked, arses spanked. Imagine that, paying someone to smack your arse! Johnny’s … fucken … old Pius, he woulda made himself a fortune in his day.

In his day.

Johnny dont know the girl’s name, but he says to her anyhow:

Hey little Susie, hey.

She stops for a second and swivels her head. Heavy drip at the tip of her nose. She must be hurting, yeah, making a beeline for Shiner’s gear. He says to her:

Tell Shiner I needs him to drop down, tell him it’s Johnny. Can you do that for me?

Susie nods and mumbles, totters on up the hill. She’s hurtin now, she’s feelin it.

Quite the package. Somebody’s daughter. Christ knows what kinda wars she’s come through before she landed in Shiner’s lap.

Johnny’s back to the garbage man’s door and raps again, hard this time. Just a nudge, you know, one little bump and you knows the glass is going in onto the porch floor. If that’s the way shit goes down.

Cold sting on the knuckles.

Hey Johnny, is that your phone going off now, up the stairs?

Listen.

Is it?

Just your luck, first time you stepped out tonight.

Fucken phone.

Buddy’s missus comes to the window. No comment from Johnny, but still and all it must be nice. Must be a fine life for some. They got these red lights on in there, nice hanging lamp with a red bulb that looks all cozy and slutty seductive all the one time. Must be nice. Atmosphere. She goes for the handle and then sees it’s not someone she knows and then sorta raises her eyebrows at Johnny.

That’s your phone going off Johnny, listen … Fuck.

I needs to talk to your fella, Johnny goes.

—

Excerpted from WE’LL ALL BE BURNT IN OUR BEDS SOME NIGHT. Copyright © 2017 by Joel Thomas Hynes. Published by HarperPerennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Boundary by Andrée A. Michaud

The children had long been in bed when Zaza Mulligan, on Friday 21 July, stepped onto the path leading to her parents’ cottage, humming “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” flung out, in the bedazzlement of that summer of ’67, by Procol Harum, along with “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” She’d drunk too much, but she didn’t care. She loved seeing objects dancing about her and trees swaying in the night. She loved the languor of alcohol, the odd gradients of the unstable ground, forcing her to lift her arms as a bird unfolds its wings to ride the ascending winds. Bird, bird, sweet bird, she sang to a senseless melody, a drunken young girl’s air, her long arms miming the wings of the albatross and those birds of foreign skies that wheel over rolling seas. Everything around her was in motion, all charged with indolent life, right up to the lock on the front door into which she couldn’t quite manage to insert her key. Never mind, because she didn’t really want to go in. The night was too lovely, the stars so luminous. And so she retraced her steps, crossed back over the cedar-lined path, and walked with no other goal than to revel in her own giddiness.

A few dozen feet from the campground she entered Otter Trail, the path where she’d kissed Mark Meyer at the start of summer before going to tell Sissy Morgan, her friend since always and for evermore, for life and ’til death do us part, for now and forever, that Meyer frenched like a snail. The slack memory of that limp tongue wriggling around and seeking her own brought a taste of acid bile to her throat, which she fought off by spitting, barely missing the toes of her new sandals. Venturing a few awkward steps that made her burst out laughing, she moved deeper into the woods. They were calm, with no sound to disturb the peace in that place, not even that of her footsteps on the spongy earth. Then a light breath of wind brushed past her knees, and she heard something crack behind her. The wind, she said to herself, wind on my knees, wind in the trees, paying no heed to the source of this noise in the midst of silence. Her heart jumped all the same when a fox bolted in front of her, and she started laughing again, a bit nervously, thinking that the night gave rise to fear because the night loves to see fear in the eyes of children. Doesn’t it, Sis, she murmured, remembering the distant days when she tried with Sissy to rouse the ghosts peopling the forest, that of Pete Landry, that of Tanager, the woman whose red dresses had bewitched Landry, and that of Sugar Baby, whose yapping you could hear from the top of Moose Trap. All those ghosts had now vanished from Zaza’s mind, but the sky’s moonless darkness revived the memory of the red dress flitting through the trees.

She was starting to turn off onto a path that intersected with Otter Trail when there was another crack behind her, louder than the first. The fox, she said to herself, fox in the trees, refusing to let the darkness spoil her pleasure by unearthing stupid childhood terrors. She was alive, she was drunk, and the forest could crumble around her if it wished, she would not shrink from the night nor the barking of a dog that had been dead and buried for ages. She began to hum “A Whiter Shade of Pale” among the swaying trees, imagining herself in the strong arms of someone unknown, their dance slow and amorous, when she stopped short, almost tripping over a twisted root.

The cracking came closer, and fear, this time, began to steal across her damp skin. Who’s there, she asked, but silence had fallen upon the forest. Who’s there, she cried, then a shadow crossed the path and Zaza Mulligan began to retreat.

—

Excerpted from BOUNDARY. Copyright © Andrée A. Michaud, 2014 Translation copyright © Donald Winkler, 2017. Published by Biblioasis International Translation Series. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Tumbleweed by Josip Novakovich

Most were amateur drunks; a friend of mine, a few years older than me, informed me that alcoholism was a disease, first defined as such by the United States in 1956, coincidentally my birth year. Previously, alcoholism was a phenomenon, now it was a disease. Pop (my friend) explained to me that there were all sorts of alcoholics, such as rakijasi (brandy drinkers), pivasi (beer drunks) and, worst of all, vinasi (winos). Something in wine hooked these people incurably. I said, I don’t know any winos. Oh, you can recognize them easily, said Pop. They dehydrate, so when you see a man drink several glasses of water in the morning, you might look for the correlation of wine in the evening and water in the morning. Nobody needs to drink water in the morning except alcoholics, he claimed.

However, winos were not all that bad, it turned out. Namely, when I needed to visit Belgrade to take a TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) so I could apply to American colleges, I said to Pop, I can’t afford a hotel in Belgrade. Do you know where I could crash for the night before my test? No problem, Pop replied. I know a wino who has a little house in Zemun just outside Belgrade, with excellent bus links to the centre. How do I get in touch with him? Should I go to the post office and call him? Oh no, he’s always home. I’ll give you the address. Just go there, bang on the door — he’s hard of hearing — and say you are Pop’s friend, and give him a one-litre bottle of red wine. You’ll be his best friend right away. And you can sleep over. Now, maybe he’ll be in a good phase, maybe not. His father is an officer, so he’s protected, but still, now and then the police, who hate winos like him, come over and slap him. For a while they came every morning and woke him up by slapping his face and kicking him. His father probably sent them to do that.

I followed Pop’s instructions. It was a snowy and windy day in February. I came to a triangular square, found the little house with two shattered windows, and banged on the door. Misho opened the door, tall, dishevelled, with somewhat purple undersides to his eyes. I introduced myself, and he laughed, Josip, like Byeli. You must be Croatian, he said, as though everybody loves Byeli in Serbia and nobody would name children after him. Oh, and what do I see, a bottle of red. Yes, I replied, Plavac from Peljesac, Zinfandel from the Peljesac Peninsula. Pop says I can spend the night here. I have to take tests at the American Embassy tomorrow. At the American Embassy! Misho replied. By all means.

We sat down and lit a petroleum lamp. I haven’t paid for the electricity in a year, so the city cut me off, he explained. The petrol fumes and smoke drifted, while he popped open the bottle and drank straight from it for a long while, finishing half. Good, now we can talk, he said. If you’re tired, you can go right to bed. Use that down cover.

I shivered as the snow blew through the windows into the room and the wind whistled cheap melodies over the shards of glass. Misho walked to the cupboard, yanked a glass door open, and took out a handgun. Do you want to check it out? he asked. No, I’m fine here, I said. It’s really cold; I don’t want to leave the bed. It’s an interesting gadget, he said. My grandfather had an argument one day with my grandma. She was in bed just where you are, in the same bed, at midnight, like now; it’s midnight, isn’t it? We haven’t changed the furniture here since World War One. And he shot her. Yes, my friend, he killed my sweet grandma right there, with three bullets.

He sobbed, and threw the handgun to the floor. He drank more wine, the snow blew through the cracked windows, and I shivered. Would you like a sip? Misho asked. We need more wine, this is such damn good Croatian wine. No, thank you, I replied. Somehow, at that point I passed out and slept.

I woke up at dawn, found Misho asleep in the armchair, covered with a large green officer’s overcoat, with a couple of shoulder stripes, probably his grandfather’s from World War One, and I walked out into the biting wind, stepped onto the bus, and soon I was at the American Embassy. The administrators all smiled, displaying their enviably white teeth, and gave me a B2 pencil, to shade the ovals of the correct answers. They all drank water and I eyed them suspiciously.

—

Excerpted from TUMBLEWEED. Copyright © Josip Novakovich 2017. Published by Esplanade Books / Vehicule Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Minds of Winter by Ed O'Loughlin

HOROLOGISTS PONDER MYSTERY OF HOW 19TH CENTURY CHRONOMETER SURVIVED FATAL ARCTIC EXPEDITION

Timepiece linked to Sir John Franklin’s fatal Arctic expedition returns to Britain disguised as a carriage clock

By Maev Kennedy

Guardian, London,

Wednesday 20 May 2009, 15.26 BST

In a mystery worthy of Agatha Christie, a valuable marine chronometer sits on a workbench in London, crudely disguised as a Victorian carriage clock, more than 150 years after it was recorded as lost in the Arctic along with Sir John Franklin and his crew in one of the most famous disasters in the history of polar exploration.

‘I have no answers, but the facts are completely extraordinary,’ said the senior specialist on horology at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, Jonathan Betts. ‘This is a genuine mystery.’

When and how did the timepiece return to Britain, is it evidence that somebody survived the disaster, or of a crime – even murder?

Betts has no idea – but he does know its shining brass mechanism could never have spent months in the ice, exposed to salt-laden Arctic gales. It must have been stolen from the ship, or from a crew member who cared for it up to the moment of their death.

‘This has never been lying around in the open air. I have handled a pocket watch recovered from the expedition, and it is so corroded it is not possible even to open the case. Conditions in the Arctic are so extreme this would have rusted within a day, and been a heap of rubbish within a month.’

The chronometer returned to the same building – once the Admiralty store from which it was issued, now Betts’ clocks workshop at the Royal Observatory.

The apparent fate of the superb timekeeper, made in London by John Arnold, after it was issued to Sir John’s ship, is clear from the official ledger also on Betts’ desk. Under ‘Arnold 294’, the faded sepia ink reads: ‘Lost in the Arctic Regions with the “Erebus.’ In the final entry, on 26 June 1886, more than 40 years after it disappeared, it was officially written off.

The fate of Franklin in 1845, his two superbly equipped ships carrying two years’ worth of supplies, including barrels of lemon juice to ward off scurvy, his 129 men who starved, froze and were poisoned to death in the ice, and the suggestion that some survived for a time by cannibalism, haunted the Victorian imagination.

A record 32 rescue expeditions were sent, spurred on by his formidable widow, Jane.

Inuit witnesses described Englishmen dying where they fell in the ice, apparently without ever asking how the natives survived such extreme conditions.

Rescue expeditions brought back papers recording the death of Franklin, abandoned clothes and equipment, caches of supplies including poorly sealed tins of meat that may have killed many of the men, and eventually skeletons. Every scrap of evidence was recorded – but there is no record of anyone setting eyes on the chronometer again.

It is clear to Betts that whoever converted it into a carriage clock for a suburban mantelpiece knew they were dealing with stolen property. The evidence of a crime concealed is on the dial, where Arnold’s name was beaten flat, and an invented maker’s name substituted – and then changed back again when the clock was sold 30 years ago and a restorer spotted Arnold’s name on the mechanism.

The Observatory bought it when it came up for sale again 10 years ago, but its true history emerged when Betts dismantled it, and matched it with the 19th-century records. None of those who handled it after conversion could have guessed its connection with the Franklin expedition.

It will be on public display for the first time in an exhibition opening on Saturday at the National Maritime museum, on Britain’s obsessive quest to find the legendary North West Passage to the east through the Arctic ice, which over centuries cost the lives of Franklin, his men and hundreds of other explorers and sailors.

Among poignant artefacts, including a sledge flag embroidered by his widow with the motto ‘Hope on Hope Ever’, one of the still-sealed cans of meat and the revolting contents of another opened in the 1920s, visitors will see the rather dumpy carriage clock, with three fat little ball feet and a carrying handle crudely bolted onto the chronometer’s original brass case.

Betts believes the only possible explanation for the conversion was to make Arnold 294 literally unrecognizable. Stealing a valuable piece of government property from an official expedition would have been a serious crime, punishable by transportation if not death. He yearns to know who dunnit.

North West Passage: An Arctic Obsession, National Maritime

Museum Greenwich, 23 May–20 January 2009

—

Excerpted from MINDS OF WINTER. Copyright © 2016 Ed O’Loughlin. Published by House of Anansi Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next Year for Sure by Zoey Leigh Peterson

Chris doesn’t even know if Emily believes in god. (Or poetry, for that matter, or interplanetary travel.) He knows that she swears impressively but never goddamns anything — not once in their seven conversations. He knows that she lives in a crowded, bustling house called Ahimsa, but the house would have been named long before Emily moved to town and took over this part of his brain. And he knows that when he asked if she’d like to come apartment-sit over the long weekend, she used the word sanctuary, and said it in a way that stilled the air.

————

I think I have a crush on Emily, he tells Kathryn in the shower. This is where they confide crushes.

A heart crush or a boner crush? Kathryn says.

He doesn’t know how to choose. It’s not particularly sexual, his crush. He hasn’t thought about Emily that way. And Chris would never say boner. But it’s not just his heart, either. It’s his molecules.

So he tells Kathryn about his molecules. How the first time he met Emily, it felt like his DNA had been re-sequenced. How he felt an instant kinship and a tenderness that was somehow painful. How, whenever he talks to her, he comes away feeling hollowed out and nauseous like after swimming too long in a chlorinated pool. And how — this, sheepishly — he has spent days arranging and rearranging their bookshelves and postcards and takeout menus, to make the apartment not only as welcoming as possible but as informative. As compelling.

You’re awesome, Kathryn says.

Kathryn gets into bed still wet, the way she likes, and Chris makes the bed around her. A pillow between her thighs, a kiss on each knee, one arm tucked between the sheet and the blanket. She does this thing, this purring sound in her throat, which he has never been able to approximate.

Chris slides under the covers and wraps himself around her. She burrows, nestles with contentment, but then seems sad.

I wish Sharon and Kyle were coming, she says.

Me too, he says. But it’ll still be good. He holds her and tells her all the ways it will still be good. Four days in the woods — no cars, no phones, no people. Four days alone with her favourite person in her favourite place with her favourite foods. She smiles. He walks her through each meal they’ve planned, the ingredients premeasured and packed into satisfyingly compact little bundles on the backs of their bikes. She nods and mmms until she starts to twitch and is away.

Chris tries to let himself be pulled down by the warm suck of her undertow, but he is left lying in the dark. In his head, he starts to compose the offhand note he will write as they rush off the next morning. Hi Emily, Please make yourself at home. There is white wine in the fridge, and red — Hi Emily, Everything you see is yours. Hi Emily, I love you. Hi Emily, We’ll be back Monday night. Hope you have a great weekend! Love, Chris.

Love, Chris & Kathryn.

Kathryn & Chris.

It’s a two-hour ride to the big ferry, then another two hours on the other side, then a smaller ferry, another ride. By the time they get to the campsite, it will be dusk. But right now it’s still dewy and cool and they are taking it easy. Normally, there’d be the four of them riding in a line, and he knows Kathryn’s favourite thing is to ride at the back and watch them all snaking through the city, loaded with gear. Today they are riding side by side because it is too lonely not to.

Kathryn has been a little sad all morning, so to cheer her up, Chris has been amusing her with the fussy, imperceptible measures he has taken to prepare the apartment for Emily: vacuuming the coils behind the fridge, relabelling their ragtag spice jars, hiding their exercise tapes. Nothing invigorates Kathryn like a good crush — more often hers, but especially his — and she was quick to make it into a game they could both play. After they’d put on fresh sheets for Emily, Kathryn insisted they roll around on the just-made bed.

If it looks too neat, she said, it feels forbidding. What you want is a deep, deep sense of clean, yes, but then a surface that is—

(And here she made a gesture that was at once inviting and nonchalant.)

They rolled and cavorted on the bed until it needed to be made all over again.

On the smaller ferry, they stand away from their bicycles so they don’t have to field questions from bored drivers. They lean on the railing and gaze out over the water.

I used to always see whales on the ferry when I was a kid, Kathryn says. She is stretching her calf muscle without taking her eyes off the horizon. I thought that was the whole point, she says, the whales. The first time they didn’t come, I told my mom she should get our money back.

Chris always likes this story. He likes to look inside her brain and see how it works, like an ant farm or a cutaway model of a submarine — he never gets tired of looking.

He tells her, again, about the time his family went camping and how he woke up one morning to find two killer whales playing in the water just off the shore, and how he stood there for half an hour, not twenty feet from his family asleep in their tents, and never woke them up.

Her eyes well with fresh love. Sometimes Chris wonders if Kathryn remembers his stories; it often seems like she’s hearing them for the first time. But then at other times they’ll be talking and Kathryn will pluck a thread from a story Chris himself has long since forgotten, and he feels profoundly plumbed.

I hope you’d wake me up, she says.

I would definitely wake you up, he says.

He doesn’t know why he hadn’t woken his family. Or why he had hoped, almost prayed, that they wouldn’t wake up on their own. Or why, after only a few minutes, Chris had started to wish the whales would leave, even while he couldn’t stop staring and gasping with joy.

Kathryn presses into him, and they stare out over the teeming ocean. They see no whales.

—

Excerpted from NEXT YEAR, FOR SURE. Copyright © 2017 Zoey Leigh Peterson. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Bellevue Square by Michael Redhill

I was alone in the store, shelving books and humming along to Radio 2. Mr. Ronan, one of my regulars, came in. I watched him from my perspective in Fiction as he chose an aisle and went down it.

I have a bookshop called Bookshop. I do subtlety in other areas of my life. I’ve been here for two years now, but it’s sped by. I have about twenty regulars, and I’m on a first-name basis with them, but Mr. Ronan insists on calling me Mrs. Mason. His credit card discloses only his first initial, G. I have a running joke: every time I see the initial I take a stab at what it stands for. I run his card and take one guess. We both think it’s funny, but he’s also shy and I think it embarrasses him, which is one of the reasons I do it. I’m trying to bring him out of himself.

He’s promised to tell me if I get it right one day. So far he hasn’t been Gordon or any of its short forms, soubriquets, or cognomens. Not Gary, Gabriel, Glenn, or Gene and neither Gerald nor Graham, my first two guesses, based on my feeling that he looked pretty Geraldish at times but also very Grahamish, too. He’s a late-middle-aged ex-academic or ex-accountant or someone who spent his life at a desk, who once might have been a real fireplug, like Mickey Rooney, but who, at sixty-plus years, looks like a hound in a sweater. There is no woman in his life, to judge by the fine blond and red hairs that creep up the sides of his ears.

I know he likes first editions and broadsides, as well as books about architecture and miniatures. I keep my eye out for him. And he’s a gazpacho enthusiast. You get all kinds. I always discover something new when Mr. Ronan comes in. For instance, you can make soup from watermelons. I did not know that.

He came around a corner and stopped when he saw me. He was out of breath. “There you are,” he said. “When did you get here?”

“To the Fiction section?”

“You’re dressed differently now,” he said. “And your hair was shorter.”

“My hair? What are you talking about?”

“You were in the market. Fifteen minutes ago. I saw you.”

“No. That wasn’t me. I wasn’t in any market.”

“Huh,” he said. He had a disagreeable expression on his face, a look halfway between fear and anger. He smiled with his teeth. “You were wearing grey slacks and a black top with little gold lines on it. I said hello. You said hello. Your hair was up to here!” He chopped at the base of his skull. “So you have a twin, then.”

“I have a sister, but she’s older than me and we look nothing alike.” I don’t mention that Paula is certain that G. Ronan’s name is Gavin. “And I’ve been here all morning.”

“Nuh-uh,” he said. “No, I’m sure we …” He left the aisle. My back tingled and I had the instinct to move to a more open area of the store, where I could watch him. I went behind my cash desk and started to pencil prices into a stack of green-covered Penguin crime. I flipped up their covers and wrote 5.99 in each one, keeping my eye on my strangely nervous customer. Finally, he came out of the racks with The Conquest of Gaul and put it down on my desk.

“Oh … Mr. Ronan? I wanted to tell you I found a pretty first edition of Miniature Rooms by Mrs. Thorne. Original blue boards, flat, clean inside. Do you want to see it?”

“Yes,” he said, like it hurt to speak. I brought it out from the rare and first editions case. “It’s just uncanny, it really is,” he said.

“This woman.”

“Yes! She said hello back like she knew me. I swear to god she called me by name!”

“But I don’t know your name. Right? Mr. G. Ronan? I think you dreamt this.”

“But it just happened,” he said, like that explained something to him. “And you knew my name.”

“Mr. Ronan,” I said, “I am one hundred per cent —”

I didn’t like the look in his eye. He began edging around the side of the desk, coming closer, and I backed away, but he lunged at me with a cry and grabbed me by the shoulders. Despite his size, I couldn’t hold him off and he backed me up, hard, against the first editions case. I heard the books behind me thud and tumble. “Take it off!” he shouted in my face. With one hand, he tried to yank my hair from my head. “Take off the wig!”

“Get back!” I shrieked. I pushed against his forehead with my palm. “Get off me!”

“Goddamn you, Mrs. Mason!” When a fistful of my hair wouldn’t tear off, he leapt up and stumbled backwards, his eyes locked on mine, but washed of rage. The blood had drained from his face. “Christ, that’s real!”

“Yes! It’s real! See? Real hair attached to my own, personal head.”

“Oh god.”

“What is wrong with you?”

He grovelled to the other side of the desk. “Oh my god. I’m so sorry. I must be having another attack.”

“Another attack! Of what? Do you want me to call an ambulance?”

“I’ll be okay. I’m really sorry. I don’t know what came over me, Jean. Forgive me.”

That was the first time he had ever used my name. “You scared me. And you hurt me, you know?” I began to feel the pain seep through the shock of being battered. “Are you sure I can’t call a friend or someone?”

“No. I’ll go home and lie down. I’m just so sorry.” He took his wallet out and put his trembling credit card down on the cash desk.

I tapped it for him. We stood together in a dreadful silence until I said, “Gilbert.”

“No,” he replied.

—

Excerpted from BELLEVUE SQUARE.Copyright © 2017 Caribou River Ltd. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Son of a Trickster by Eden Robinson

“Wee’git,” she’d say if his parents left them alone. “If you hurt her, I will kill you and bury you where no one can resurrect you. Get, you dirty dog’s arse.”

“I’m Jared,” he’d said.

“Trickster,” she’d said. “You still smell like lightning.”

She was a cuddly grandma with his cousins, sitting them at the kitchen table and giving them popcorn balls, homemade fudge and caramel apples. She knitted mittens with their names embroidered on the back. The last birthday present she’d given him was a jar of blood with little animal teeth rolling around the bottom.

“Fucking cuntosaurus,” his mom had said, snatching it from him. “She doesn’t believe me, does she? No faith. None.”

“Jared, buddy, this isn’t about you,” his dad had said.

“She doesn’t like me,” Jared said.

“She doesn’t mean it,” his dad said.

His mother spat. “Sonny boy, it’s got nothing to do with you and everything to do with what a fuck-up she thinks I am.”

“She’d never hurt you,” his dad said.

“Because I will fuck her up one side and down the other if she lays a single finger on you,” his mom said. “I will fuck her up good.”

When Jared was almost five, his mother decided they should move, so his dad found work at Eurocan, a pulp-and-paper mill in a town called Kitimat. His mom showed it to him on the map, tracing his finger over the ferry route they were going to take up the Inside Passage. They packed up their townhouse in one weekend, forfeiting their damage deposit. As they were loading the last boxes late in the evening, his grandmother came and stood in front of the moving truck. Jared ducked behind his mother.

“Don’t,” his dad said, grabbing her arm. “Maggie. Think.”

His mom jerked her arm away. His dad lifted Jared and propped him on his hip. His mom got into the driver’s side. She revved the engine. His grandmother stared at his mother, waiting.

“Maggie,” his dad said.

“Momma,” Jared said.

His mom turned the engine off. She got out and went to stand nose to nose with her mother. His dad slid behind the wheel.

“I’ve lost all patience with you, old woman. Don’t push me.”

“Be careful,” his grandmother said. “You know what he did to me. That isn’t your son. It’s the damn Trickster. He’s wearing a human face, but he’s not human.”

“You’re one to talk.”

“Marguerite, listen to me. He’s dangerous.”

“Lay your old-school crap on my boy one more time and I will fuck you up your dry, lifeless ass.”

“I tried,” his grandmother said, backing down, moving to the side of the road to stand in the grass. “You have no ears.”

“Fuck off and stay fucked, cunt.”

His dad placed Jared’s hands on the steering wheel.

“Toot, toot,” his dad said. “Let’s blow this Popsicle stand, Jelly Bean.”

His mom got in the passenger side and slammed her door shut.

“I think you missed a couple of swears, Hon,” his dad said.

She gave him the stink eye. They started off for the ferry terminal. His grandma was a shrinking figure in the side mirror.

His dad stopped at a stop sign, looking both ways even though no one was around. “You should learn some French so you can swear at her some more.”

“Are you taking her side?”

“Lord Almighty, no. Don’t run me over, Mags. Ahhhh.”

She’d slugged his shoulder. Jared rocked with his dad, whose laugh started in his belly, bouncing him against the steering wheel.

“I’m just saying Jelly Bean here is going to know the best curse words in kindergarten.”

“Damn … tooting right, he will,” his mom said.

Jared hadn’t been on a ferry since he was a baby and he was so excited when he saw it, he bounced up and down, clapping. Driving inside was like being swallowed by a giant whale, like in the stories his babysitter Barbie read to him from the Bible. His dad grabbed a backpack and slung it over his shoulder before tucking Jared under his arm like a football. They crammed into the elevator with other sleepy passengers. His dad sat Jared on his shoulders. His mom rested her head against his dad’s arm.

“It’s okay, Hon,” his dad said.

They found some seats, but Jared whined to go onto the deck and his dad agreed to take him while his mom set up their sleeping bags on the floor. The wind was cold and the ferry gave a toot before pulling away from the terminal. Jared covered his ears until he was sure it was the only toot. The lights sparkled on the black water. The mountains were giant black lumps against the starry sky.

The ferry rounded a point and Jared’s dad lifted him up so he could say goodbye to Bella Bella. The buildings and streets looked different from the ferry. He waved.

“Goodbye to all that,” his dad said.

—

Excerpted from SON OF A TRICKSTER. Copyright © 2017 Eden Robinson. Published by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

The Dark and Other Love Stories by Deborah Willis

We met when we were assigned to the same canoe at summer camp. Andrea took the stern and I was in the bow. As we drifted on the placid lake, she said, “If we paddled hard, how far do you think we’d get? Before anyone caught us?”

It was the closest thing to love at first sight I’ve ever found. At summer camp, the days are long and friendships are quick and intense. After that canoe ride, Andrea and I sat beside each other at meals, played on the same sports teams, and slept in adjacent top bunks. And we were always the last to fall asleep. If I closed my eyes, Andrea would stretch out one of her legs and kick something over on my shelf: my flashlight, or the bottle of calamine lotion my mom had packed for me. Something to knock me awake.

“Jess,” she whispered. “Wake up.” Her voice was quiet but demanding, and it forced me to open my eyes, to focus in the dark, to stay in our private world of wakefulness.

During the day, we participated. That’s what we called it — participating — imitating our counselor, Lisa, and her sunny way of speaking. In the past I’d enjoyed participating, but that summer, I hated everything: swim lessons, nature walks, dodgeball, arts and crafts, tennis, basketball, canoeing. Most of all, I hated horseback riding, which involved getting saddle burn as your horse walked listlessly around a ring. The horses were so tired and used to their work that we could drop the reins and they would continue at the same pace, retracing the same circuit. Andrea said riding one of those horses was like having sex with a dead person. She’d never had sex with anyone, living or dead, but she had a gift for a memorable turn of phrase. She kicked uselessly at the horse’s sides, flicked the reins, yelled, “Vamos! Caballo!” She always got in trouble for that.

Other girls fawned over the horses — brushed their manes, fed them apples, kissed their noses — but I didn’t like to touch those big, sad animals. The camp rented them from a rancher who provided horses that were too old to be of any use to him. Some had sagging bellies from bearing foals, others were scarred with bug bites. Sometimes they would sweat so much that a white lather foamed along their necks. And they weren’t gentle like the horses in books. They kicked and bit each other furtively, the way children abuse each other when their parents aren’t watching.

What I mean is, Andrea and I were thirteen and beginning to outgrow this daylight world of lessons and games and sing-alongs. We were sick of having our days parsed into hour-long blocks, sick of being led from one activity to the next. We were hungry for feral time. That’s why we loved the dark.

We remained awake until long after the other girls had finished brushing their teeth, trying on each other’s clothes, and talking about which boys they liked. We stayed up even after Lisa had flicked off the light and left the cabin, on her way to plan the next day’s activities. Andrea and I stayed up until the sky was so black that each star was outlined against it, sharp and bright like scraps of metal. That’s how we knew it was time.

We changed from our pastel pajamas into jeans and hooded sweatshirts, and put on running shoes that we’d turned from white to black with a permanent marker — my mom would freak out when I got home. We dressed quietly so none of the other girls would hear us — those girls were our friends during the day, but we didn’t want them to know what we did at night. They might tell on us. Or worse, they might want to join us.

We opened the cabin door and ducked out, careful to keep close to the small wooden building. We couldn’t let ourselves be seen by any of the counselors who sat on benches outside with flashlights and first-aid kits and boxes of Kleenex, ready to deal with bleeding noses, stomachaches, homesickness. We slipped through the night as silently as fish through water, skidding between cabins until we were far from where the other kids slept. In the dark, we felt brave. We were no longer part of that camp world. Or rather, at night, the camp itself changed to accommodate us. It ceased to be an ordered, regimented place, where we ate at the same time every day, where we sang songs after lunch, where we played sports after singing. At night, the infrastructure for these activities — the dining hall, the soccer field, the lake — seemed mysterious.

Our favorite place to go was the horses’ field. We crawled along the barbed-wire fence of the camp’s perimeter, rolled down a steep hill past the boys’ cabins, and came to the corral: a locked tack shed and a ring of close-clipped grass used for riding lessons. The horses were kept here during the day, but each night, when the lessons and trail rides were done, they were let out — set free! we called it — into an open field, where they grazed and slept. There was nothing romantic about this field during the day: it buzzed with mosquitoes, and smelled of the overflowing septic tank. But at night, these things could be ignored. At night, the field was full of moon.

To get there, we passed the corral and went through a small patch of forest. We followed trails the horses had made through the trees, and, because we never brought flashlights, had to feel our way, our hands gripping rough branches, our feet moving slowly over dirt and rocks. I’ve never thought that I have good hearing, but on those nights, I heard everything: distant coyotes, insects circling my body, my own breath.

I was only scared once. Andrea and I moved through the densest part of the forest, along a path so narrow that branches scraped my face. No moonlight could reach us, and I couldn’t see anything. I followed the sounds of twigs cracking under Andrea’s shoes. I felt the thrill of my heart in my chest.

Then there was silence. I couldn’t hear Andrea’s breathing or her steps.

“Andrea?” I figured this was a joke. “Andy?” I whispered, using the nickname she hated.

There was no reply. I held my breath and tried to quiet my body, but my heart seemed lodged between my ears.

“Andrea!” I screamed, and that’s when she grabbed me from behind and put her hand over my mouth.

“You chickenshit.” She laughed. “Do you want us to get caught?”

I could feel her heart against my back. “You’re a bitch.”

“Shh.” She still had her arms around me. “Look.”

She turned my head toward the outlines of the horses, ghostly and elegant against the black sky. At night, it was easy to forget how ordinary they were. Or rather, at night, we could see the beauty of their flawed bodies. They stood together, some of them asleep, some eating, and we could see the breath from their wide nostrils. They looked like shadows, not entirely real.

We approached the horses quietly, with the single-mindedness of lovers. It was as though Andrea and I had created them, as though they were our secret, a gift we’d given each other. They had a quiet kind of bravery, a grace I’ve rarely seen since. The only thing that comes close is the dignity of some old women — the ones who remember being beautiful, the ones who know they still are.

—

Excerpted from THE DARK AND OTHER LOVE STORIES. Copyright © 2017 by Deborah Willis. Published by Hamish Hamilton Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

I Am A Truck by Michelle Winters

He was lying to her. She had known from the second he came home the night before and experimentally said, “Hé, sais-tu quoi?” As he told her the lie, she studied him, halfamused, waiting for him to crack. He was an awful liar, but he persevered artlessly in his tale of a fishing trip on Saturday with the men from work. Their twentieth wedding anniversary was next week and Agathe wasn’t about to challenge him on trying to cover up a surprise for her. In fact, she was relieved. Réjean had been so odd lately—distracted, distant…Only in bed was he fully engaged, and there they were trying something new. Their physical relationship had flourished over the years, despite the normalcy and tedium innate in all couples, and despite what Agathe considered to be the loss of her figure. As early as her twenties, her body had succumbed to a condition that afflicted generations of women in her family: a ballooning of her upper half, while her legs remained coltish and slim. As her top half grew, the weight strained her spine, giving her a subtle hunch that would grow more pronounced as the years wore on. But every new pound only enticed Réjean more as he kissed and bit and squeezed her extra flesh. For him, she would always be the girl who had awakened his soul that July day at the marché when they were teenagers.

Agathe had been watching the eaves for birds while her mother examined potatoes. When Réjean suddenly appeared, his eyes already on her, he saturated her field of vision. Agathe’s knees buckled and she slid to the ground. Édithe Thibeault was quick and sharp, tossing the bag of potatoes into the air and catching her daughter before she hit the ground. As the potatoes rained down, Édithe looked up and also set disbelieving eyes on Réjean. At only fifteen, he was close to seven feet tall, with a chest as big as a rain barrel and arms the size of a normal man’s legs. His hands were like a bunch of bananas. He was already working on the downy beginnings of his moustache. For her part, Agathe had just the year before peeled her way out of a rind of unremarkability, emerging that summer a very pretty girl. Her mother’s friends would comment that Agathe was now pretty enough to be a newscaster or a figure skater and that perhaps, her beauty would be the thing to finally put P’tit Village on the map. For Réjean, she became existence itself. He broke from his brothers and swept in, hands extended, and, without a word, pulled up both Agathe and her mother so that their feet briefly left the ground. His eyes locked on to Agathe’s until he turned to join his brothers, gazing over his shoulder at her. When she had finally lost sight of his back in the crowd, Agathe began to cry.

On returning from the market, Réjean asked his mother for a haircut and presented himself at the Thibeaults’ door later that same afternoon, hair clippings still in his ears, asking if Agathe would like to go for a walk. He couldn’t have expected that once they reached the woods at the end of the street, Agathe would grab him and pull him to her, knocking the breath out of them both. They had to wait three years to get married.

They’d learned early on that Agathe was missing one of the parts needed to make babies, which made them sad at first, then overjoyed when they realized they didn’t want babies, only each other. “Il n’y a que nous,” they would say, making a tunnel between their eyes with their hands.

Réjean said that the fishing trip should be wrapped up by dinnertime. Even if the fishing part wasn’t true, he wasn’t so foolish as to lie about when he would be home. Agathe had nearly eight hours to work on her surprise for him.

From between the box spring and mattress, she pulled her bloc-notes and pencils. They had agreed this year they would make gifts for each other. She had been toiling solidly for two weeks while Réjean was at work. She brought her materials to the table, put on a pot of tea, and emptied the ashtray. Agathe had initially started smoking as a means of trying to control her weight, but her top half only continued to swell—along with a new love of cigarettes.

She flipped to her drawing on the pad. It wouldn’t matter that she was working from a photo in the newspaper; it looked enough like the Silverado that Réjean wouldn’t know the difference. Agathe was pleased with just how much her drawing resembled the photo, and planned to put the picture in a frame she had taken from a watercolour painting in the basement.

Réjean had never owned anything but a Chevy and revered the brand with a feverish loyalty. Every year, he replaced his current truck with the newest model, not because the old one was lacking or showing signs of wear, but because every truck that Chevy brought out Réjean would declare more phenomenal than the last. He often lost himself in grateful praise of the corporation for designing such a sturdy vehicle with such excellent handling.

“C’est un beau truck, ça.”

Not long after they were married, the lumber work in P’tit Village began to dwindle, but Réjean had heard that it was plentiful in nearby English-speaking Pinto. They moved into a cottage in the woods there, and began a life of increasing seclusion, and the prospect of communicating only with each other in a town where no one spoke French. Agathe and Réjean understood English, but held it in heavy contempt—even if English made up half the French they spoke. At home and school, they had been taught that the Anglophone world was trying to oppress them, monopolize their culture, and eradicate their language. It was safest to agree. Being separated by language from the world around them strengthened their bond of exclusivity. Gradually, they retreated from the world altogether, existing solely for each other in the confines of their home.

“Il n’y a que nous.”

The hours sped by as Agathe worked, capturing every realistic inch, the darks and lights, blending bits of pencil with the twisted end of a tissue and her fingers. Smudging the lines was her favourite part. It looked so real. In real life, things were smudgy. As she reproduced the positive and negative spaces of the photo, she imagined what she and Réjean might try out when he returned that night. Perhaps they could include the Silverado. She thought about a game where she was a truck driver and Réjean a trusting hitchhiker, until the sun went orange in the sky and she remembered dinner.

If Réjean was any kind of liar, he would bring home fish, even if it meant buying it at the store. She would need to assist the lie by anticipating fish and making something complementary. She would make scalloped potatoes. Scalloped potatoes were always appropriate.

She hid her drawing back beneath the mattress and returned to the kitchen, where she devoted herself to the extrathin slicing of potatoes and onions, loading the first layer into the pan, nearly skipping to the refrigerator for more cheese.

When she heard Réjean pull into his spot in front of the house, she checked the kitchen for any pencil-darkened clues. But as her eyes passed the window and stopped on the spot where the Silverado should be, she found it occupied by a police cruiser. There were two officers up front, who talked for a moment in the car before making their way to the door and knocking gently.

“Good evening, ma’am. Are you the wife of Réjean Lapointe?”

“Ouah…”

“Does your husband drive a black Chevrolet Silverado?”

“Ouah…”

“Would it be all right if we came in?”

They stood inside the door, because she didn’t invite them to sit, and asked a lot of rude questions about Réjean and their relationship: Did he seem happy? Were they having any problems in their marriage?

“Beunh, non,” she replied emphatically, and told them about their upcoming anniversary and the surprise he was without question preparing right now.

“Has he been distracted or at all different lately? Anything unusual?”

Agathe reached for her cigarettes.

“Ma’am, your husband’s empty truck was reported not far from here, sitting on the shoulder with the driver-side door open. Do you have any idea why that might be?”

She did not.

—

Excerpted from I AM A TRUCK. Copyright © Michelle Winters, 2016. Published by Invisible Publishing. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Of the 2017 longlist, the jury writes: