2022 Broadcast

On November 7, 2022, Suzette Mayr was named the winner of the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize for her novel, The Sleeping Car Porter, published by Coach House Books, taking home $100,000 courtesy of Scotiabank.

2022 Shortlist

The 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its shortlist on Tuesday, September 27, 2022. The five titles were chosen from a longlist of 14 books announced on September 6, 2022.

Lesser Known Monsters by the 21st Century by Kim Fu

Jury Citation

An endlessly surprising story collection without a single flawed entry in the bunch, Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century is brilliantly textured. Moving from an argument with the operator of a VR machine to an insomniac’s encounter with a veritable sandman to a couple who can die and resurrect themselves at will, Fu’s worlds are fantastical and enterprising in their own right. But these set-ups stealthily reveal themselves to be structures for unspeakably moving revelations about the most real of human experiences—grief, anger, mistrust, sex, nostalgia, sacrifice. A deeply emotional collection that delights, dares, and dazzles.

Stray Dogs by Rawi Hage

Jury Citation

The short stories in Rawi Hage’s Stray Dogs fuse spare, graceful language with world-spanning design. Haunted by war and movement, families fragment and cultures stretch. As the characters cross borders in pursuit of careers and relationships, they are pulled back through fissures in memory. We follow academics and photographers to Montréal, Berlin, and Tokyo, and yet those geographical distances can appear less vast than the cultural distance between a childhood in rural Lebanon and a privileged adulthood in Beirut. Just as travel is grounded by return, accomplishment is undercut by uncertainty, and urbane arrogance often rests on a foundation of humble circumstances. Movement is met with recurring meditations on the static images of photography. The writing is streamlined and confident, understated and wry. As the stories develop, we are confronted by their surprising, lifelike inevitability.

We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

Jury Citation

Through a stirring intergenerational saga that spans decades and continents, Tsering Yangzom Lama deftly unearths how exiles create home when their homeland has been stolen. With tender authenticity, We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies delicately and vigorously illustrates the ongoing human cost of Tibetan displacement, and the resolve of refugees to uphold a strong diaspora despite the violence of colonialism. The Tibetan women at the centre of Lama’s story are bound by an unflinching love for each other, their people, and the country to which they can no longer return. Vast in time, space, and feeling, this determined novel builds a vibrant world that’s both expansive and exact. Each line carefully bears the weight of longing for what once was, and the hope to sustain an uprooted culture still coming to be. Regenerative in spirit, the pages of this story are both an homage to survival and a home for the exiled.

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr

Jury Citation

Suzette Mayr brings to life –believably, achingly, thrillingly –a whole world contained in a passenger train moving across the Canadian vastness, nearly one hundred years ago. As only occurs in the finest historical novels, every page in The Sleeping Car Porter feels alive and immediate –and eerily contemporary. The sleeping car porter in this sleek, stylish novel is named R.T. Baxter –called George by the people upon whom he waits, as is every other Black porter. Baxter’s dream of one day going to school to learn dentistry coexists with his secret life as a gay man, and in Mayr’s triumphant novel we follow him not only from Montreal to Calgary, but into and out of the lives of an indelibly etched cast of supporting characters, and, finally, into a beautifully rendered radiance.

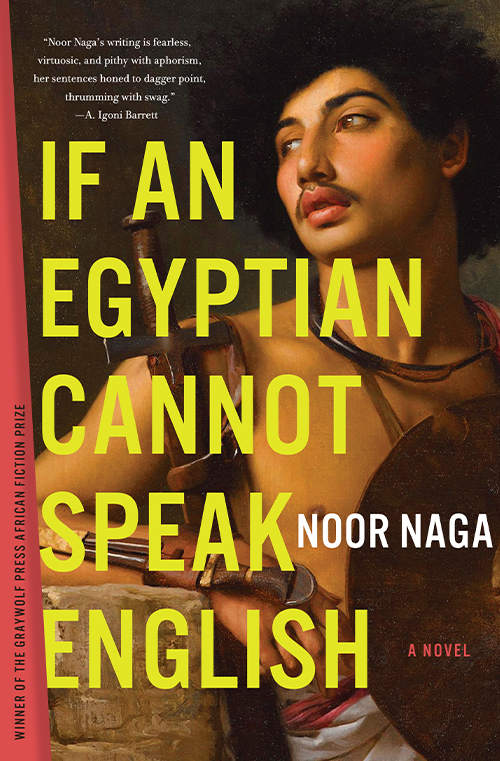

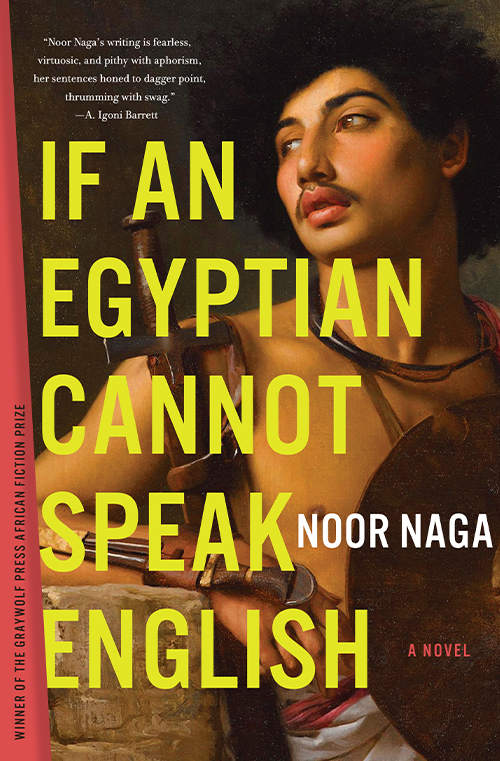

If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga

Jury Citation

A work of startling emotional depth and intellectual rigor, Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English probes the ethics of identity, desire, privilege and storytelling. Set in Cairo in the wake of the Arab Spring, the novel tracks the relationship between a troubled Egyptian photographer, and an Egyptian American woman recently arrived in the city. It is at once a love story, a disquisition on politics, an exploration of trauma, and a deft work of meta fiction – a slim novel that at times seems almost infinitely capacious. Naga is a bold writer, unafraid of complexity and complication. She is also a magician with language. Every sentence in this exhilarating novel astonishes and provokes; in the end, the relationship Naga probes most urgently is our relationship with language, its power to coerce and control, and its power to liberate.

2022 Longlist

The 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its longlist on Tuesday, September 8, 2022.

A Minor Chorus by Billy-Ray Belcourt

Billy-Ray Belcourt (he/him) is a writer from the Driftpile Cree Nation. He won the 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize for his debut collection, This Wound Is a World, which was also a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award. His bestselling memoir, A History of My Brief Body, won the Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and the Governor General’s Literary Award. A recipient of the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship and an Indspire Award, Belcourt is Assistant Professor of Indigenous Creative Writing at UBC.

Instagram: @nakinisowin

Twitter: @billyrayb

Facebook: /billyray.belcourt

Website: billy-raybelcourt.com

A Minor Chorus by Billy-Ray Belcourt

A guard handcuffs me and pushes me away from the visitors’ station. In my unit, there’s a small room just off the foyer with a glass ceiling. When it’s sunny, I sit in there and think about everything that’s ever happened to me. When I woke up this morning, I felt the heat before I opened my eyes and knew the sky was blue. If I’m allowed, I think I’ll stay in there for the rest of the day. I’ll close my eyes and end up somewhere else for a little while. Maybe I’ll end up back on the rez. Before I learned to drive, I walked along a winding dirt road from my house near the lake to the centre of the rez where most of my cousins lived. If I concentrate hard enough, if I drown out the noise of the other inmates and the officers, I might hear the rocks shift under my feet. I might hear the birds and the barking dogs and the wind in the trees and someone’s uncle telling someone’s kids to stay safe. And, if I can empty my mind enough, forget where I am for a second or two, I might remember what it felt like when, upon returning, I’d see kokum waiting for me on the patio as if she could sense that I was nearby. Even from far away, I would see her waving at me, smiling.

A Problem of Form

It was a late afternoon at the start of August when I went to the university to meet up with River, a dear friend and graduate student in the Department of Sociology who hailed from a reserve to the south, to make sense of the desire to remake my life. I wanted to leave academia. This thought, which wasn’t so much intrusive as it was a response to an ongoing crisis of creativity, permeated my days.

I was waiting in front of one of the oldest buildings on campus, a neoclassical hallmark of the Humanities quad called Old Arts. The entrance was replete with tributes to the architecture of antiquity; on either side of the steps were pillars, and above each of those were another pair. Foliage sprawled across the facade, illuminating rather than obscuring the ornate brickwork. Because it was outside the normal academic year, there was no one else around me. The effect of all of this was that in my Cree body in the twenty-first century I was a historical anomaly. On this day I was fine with projecting my feelings of alienation onto what was so clearly a product of a longing for a heroic white past, however mythological. In fact, it felt rebellious to do so.

It wasn’t that I had been wronged by the university per se. Rather, something inside me shifted in the last year such that I was no longer moved to play by its rules. I was meant to be writing a dissertation, but what the sentences I’d been compiling in a document really added up to was a depression diary or a lover’s discourse. I’d been writing about the politics of race and sadness, yes, but most days this “research topic” was more accurately a kind of self-directed behavioural therapy. I’d been experiencing life as a problem of form: it is difficult to live in a world that corrodes freedom. The shape of my days was fuzzy, imprecise. My body took on that fuzziness. I wanted to take a sledgehammer to the past to let in the shimmer of a light I didn’t know was there all along. It seemed unavoidable that I now wanted my writing not to advance an institutional body of knowledge, as is the case with a dissertation, but instead to invent an exit route, to make something out of nothing, to prop up a landmark for a place that was nowhere and everywhere. At first I assumed that because I felt both uprooted and stuck, I was going through a more acute depressive episode than usual, but I realized that I had been overtaken by new ambitions, a more consuming kind of hunger—a hunger for another way of being in the world. I couldn’t unsee everything my gut told me I was missing out on.

It was still summer nonetheless and there was still the greenery, which was so lush and overwhelming it was something of an argument for optimism, a reminder that I had to be alert to the beauty in excess, the beauty in things that quietly endured despite their unbeautiful contexts. If I admired my own abundances, my own little rebellions against subjugation, I reasoned, I could learn to be as alive as possible. It seemed silly I hadn’t come to this conclusion sooner.

As always, River looked effortlessly queer. Their dress was structured unconventionally, defying geometrical norm, and because of this it told a story of an interesting inner world. I smiled at the sight of it. We were seated at a table near the back wall. The café was a campus staple and was typically at capacity from September to April, emptier now given the student exodus from the neighbourhood in summer. The mood was artful, liberal—a Phoebe Bridgers song was playing. The most memorable aspect of the establishment was its walls, which over the years had been graffitied by patrons and commissioned artists from around the world. Above my head, for example, was a drawing of a police car that had been set ablaze. And beside River was an almost invisible sentence that sounded to us like the rallying cry of our generation: “write poems, eat ass, & dismantle private property.” They took a picture of the quote to post to Instagram later.

River studied arts-based anti-oppressive education. Their research project was community-driven: they worked with inner-city organizations to administer programs aimed to empower Indigenous youth. We’d met during our coursework year in a class called Politics & Gender. It was a small seminar with a professor who became popular and beloved for never assigning texts authored by men. Our bond was citational (we read the same scholars) as well as circumstantial (we were the only Indigenous students in the course and resultantly gravitated toward each other). Soon after, it became familial: we studied together in the library, roomed together at conferences, went on annual gaycations to the West Coast. Our friendship felt metaphysically ordained. Alas, time had gotten away from us; it’d been weeks since we’d last seen each other.

How’s fieldwork been? I asked. From what I’ve seen online, you’ve been incredibly busy.

Fieldwork’s been magical, River said. The other day I did a writing workshop using Audre Lorde’s poems on silence and her calls to build alternative models of social action that uplift the oppressed. The youth really got it, wrote these heartbreaking poems about what they wished they could say if they could figure out how to not be afraid. At the end of the session, I told them they did figure it out, that they weren’t as afraid as they thought they were. I cried.

So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive. “A Litany for Survival,” right? I said.

Exactly. I teach it whenever I get the chance.

I wrote that line on the mirror in my bedroom in my first-ever apartment, I said. It’s such an egalitarian notion. I felt caressed by it. I felt that Lorde gave me access to an openness I hadn’t had before. By virtue of what we as marginalized peoples have survived, against the odds, we speak with at minimum a kind of political possibility. Our ancestors very literally survived genocide. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to process the magnitude of that. One of the most enduring problems of my twenties, I continued, is that few, especially those in power, allow that knowledge to alter how they act. That’s a kind of silence we have to live with, isn’t it?

Yes, yes, it’s absorbing, River said. It makes me think of how for years now we’ve been protesting injustice after injustice and as a result our way of being in the world is always shifting. In the midst of tragedy, we wake up differently and go to bed differently. Then I walk through campus and it feels as if nothing of concern is happening elsewhere.

—

Excerpted from A MINOR CHORUS. Copyright © 2022 by Billy-Ray Belcourt. Excerpted by permission of Hamish Hamilton Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

In the City of Pigs by André Forget

André Forget was born in Toronto and raised in Mount Forest, Ontario. He is the former editor-in-chief of the Puritan, and his work has appeared in a variety of magazines and newspapers in Canada and the United States. He splits his time between Toronto, the United Kingdom, and Russia.

In the City of Pigs by André Forget

XVII

The concert fell on the second Saturday in April. I was filled with a certain unease, a quickness of breath that came on me when I thought about the heat rising from Theresa’s buttocks. I had caught a glimpse of something unpleasant inside myself, something aggressive and sadistic; I enjoyed feeling the poison waters closing above my head.

At eight o’clock, after I’d showered and drunk a pot of coffee, I received a text message from an unknown number. I responded with the code I’d been given when I purchased my ticket (Theresa had told me what to do) and walked down to the small park on Queen Street between nine and ten, to wait for further instructions.

A small knot of people had already gathered by a young maple near the path. I didn’t recognize anyone, but when I said the word Fera, there was a round of nods. I hadn’t been there ten minutes when a young man in a leather jacket appeared and told us to follow him. He asked each of us in turn if we were cops, which I assumed was part of the theatre, before leading us down a side street and around an office building, then into an alley that ran behind a row of houses. Everything felt very conspiratorial, but the whiff of transgression was tempered by the knowledge that, however naughty it might seem, nothing very bad could possibly happen. We’d bought tickets, after all. A large brick building loomed at the end of the alley. A fire escape ran in zigzags up to the roof. Our guide led us wordlessly up to the first landing and knocked three times on a metal door that had no handle. It was opened by a young woman, also wearing a leather jacket, who escorted us through a series of cramped hallways and corridors to a large, unlit space that smelled of dust and sweat and perfume. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I realized that I was standing beneath some kind of mezzanine. I stepped past the row of shadowy pillars in front of me and a cavernous space opened up. Here and there I could see strings of glowing green lights, and around me dozens of whispered conversations came together to create the sound of a buried sea.

The pillars of the mezzanine curved gently inward. Ghostly faces flitted past, and the lights blinked from the deeper darkness beneath its shadow. As I grew closer, I realized that the blinking effect was created by a crowd of people milling around a makeshift bar. A small hand-lettered sign saying $5 hung above the counter. There was no other information. I took out a ten-dollar bill and tried to get the attention of one of the bartenders. They had necklaces of green glowsticks hanging against their chests.

“What are you serving?” I whispered, when my turn came.

“It’s five dollars,” they said, pointing up at the sign.

“What’s five dollars?” I asked.

“The price you must pay for a drink.”

“Right, but what’s the drink?”

“The Nectar of the Gods.”

“Okay, but what is it really.”

“We cannot say.” A hint of irritation had crept into the bartender’s voice.

“I have allergies.”

“Are you allergic to anything in sangria?”

“No.”

“Then you should be fine.”

“Great, give me two.”

I drank one of the sangrias directly. It was shocking to think that, somewhere just a few blocks from my apartment, this enormous concert hall had been sitting empty for months. When had it been built, and for what purpose, and how long would it last? The cranes had begun to march north from Liberty Village. New condos were going up on the corner of Queen and Dovercourt. It seemed inevitable that such an unproductive space would soon find itself slated for destruction. There would be no record that this evening had ever happened, that a concert had been held in spite of the safety pedants and scolds and permit-grubbers. The music would live for a while in people’s memories, but in time (if Theresa was to be believed) it, too, would be erased. And this was what the composers and volunteers and musicians were willing to risk fines and court orders for. In spite of all the absurd posturing, perhaps filling this doomed theatre with mystery and young life for a few hours was not such an ignoble thing.

Again I wondered who was really paying for all this. Lying in bed with Theresa two nights before, I had tried to get her to disclose some information about what, exactly, I could expect. But she had just told me to read Book II of Plato’s Republic again, which hadn’t proved any more helpful the second time around. There was a great deal of talk about justice, and whether or not the best situation would be to behave unjustly while keeping the appearance of being an upright person. Then Socrates started talking about the beautiful city, the city where people lived simply and met their needs in uncomplicated ways. But Glaucon found this city too crude, fit only for swine, and told Socrates to be more realistic.

In theory, this squared well enough with the concert description. But I was left with a few nagging doubts. Socrates had given up on his beautiful city rather easily, after all, as if it were more a rhetorical gesture than an actual ideal. Later in the book, he certainly seemed happy enough with a stratified society, with philosopher kings at the top and foreign slaves down in the muck where they’d always been. It was as though the city of pigs was a kind of fantasy, an ideal of such unworldly beauty that no reasonable person could believe in it. But then perhaps I was reading too much into things. It was just a concert.

My train of thought was derailed when an ear-splitting shriek echoed without warning from somewhere in the depths of the theatre. The sound started out viciously high, a sudden, agonizing blast of pure noise settling into a kind of morbid buzz. When it finally died away, my heart was pounding and I’d spilled sangria all over myself. The burst of sound was followed by a silence that carried on so long as to become unnerving. The audience began to whisper again, but as the sound of hushed voices increased in volume and pitch, it became clear that the whispers of the crowd had been joined by the hum of strings. From the mezzanine above, a blue light crept up the dome of the hall. The contours of the room became clearer. At the front was a stage that held a large, solid mass, a kind of squat cylinder or raised disc. The music of the strings became a kind of dreadful static, unsettling precisely because it was organic, like the crunch of a hand slammed in a car door.

The noise reached an unbearable excess, and there was a sudden electrifying crack. A narrow red spotlight turned on directly above the cylinder, revealing a figure dressed completely in black and carrying a bullwhip. A piano started to play somewhere up in the mezzanine, and it was joined by another and then another placed at points around the room. Each played a complex tonal figure in staccato bursts, less melody than percussion. A kettledrum added to the din with a series of cascading triplets. Because the musicians seemed to be half a beat or so behind each other, the music was filled with strange, unpleasant echoes, a cacophonous effect that was magnified by the size of the hall and the distance between the instruments. I had no idea how they were keeping time, or if they were even trying to keep time. The collision of sound made it nearly impossible to identify a signature. Tonally it was chaos, but as the piece went on, a certain inexorable pattern emerged. The rhythms of the timpani became more regular. The piano melodies simplified into chord progressions. Something like a beat appeared, and the stupefying noise coalesced into a mechanical grunt and shudder.

It was at this point that the figure in the centre of the stage cracked its whip again, and a series of dull thuds and clanks were heard in rough time with the music. Grey light filtered in from the wings, illuminating two lines of figures in simple tunics marching with long poles in their hands.

—

Excerpted from IN THE CITY OF PIGS. Copyright © 2022 by André Forget. Excerpted by permission of Dundurn Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century by Kim Fu

Kim Fu is the author of two novels and a collection of poetry. Her first novel, For Today I Am a Boy, won the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award, as well as a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice. Her second novel, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore, was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award and the OLA Evergreen Award. Fu’s writing has appeared in Granta, the Atlantic, the New York Times, Hazlitt, and the TLS . She lives in Seattle.

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century by Kim Fu

TWENTY HOURS

After I killed my wife, I had twenty hours before her new body finished printing downstairs. I thought about how to spend the time. I could clean the house, as a show of contrition, and when she returned to find me sitting at the shining kitchen island, knick-knacks in place on dusted shelves, a pot of soup on the stove, we might not even need to discuss it. I could buy flowers. I could watch the printing, which still fascinated me, the weaving and webbing of each layer of tissue, the cross-sectional view of her internal workings like the ringed sections of a tree trunk.

I had poisoned her, a great wallop of poison in her morning coffee. So I didn’t have the defence of passion, a momentary loss of reason. Poison took forethought. Poison said: I wanted to be apart from you for a while. Then why not just leave the house? Why not go for a walk? No, it said more than that. Poison said: I wanted you to not exist for a while. I wanted to move through the world without you in it.

There’d been no choking, gasping, flailing, spewing. Connie simply keeled over at the table. The soft thunk of her weighty head, the clatter of her empty cup tipping off the saucer, spilling its dregs. Painless, I hoped, though I would have to take her word for it later, either way. A large dose for a small woman – when she’s been driving our car, I’ll find the seat raised and pushed as far forward as it goes, so she can reach the pedals and see over the steering wheel. I wrapped her briskly in a sheet, put her out on the porch, and filled out the online form for same-day pickup.

Connie has killed me only once. We’d spent a week car camping in a state park, four hours away, in that last week of the season where the frozen ground sucks heat out through the layers of your tent floor, sleeping pad, and sleeping bag, keeping most people away. She’d done most of the packing, loading the hatchback so full I couldn’t see out the back window as I drove. And then one morning, as we packed our day bags for a twenty-mile loop, she informed me she’d borrowed our neighbour Jim’s rifle. She’d told him she was afraid of bears. We called Jim an old coot in private, with affection. She slung the rifle over her back and wore it as we set off down the path. I was glad, in a way. I’d been curious about the experience, but whenever I tried to do it myself, I chickened out at the last minute.

She walked in front wherever the path narrowed, leaving me to stare at the long wooden barrel cutting diagonally across her upper back, below her short ponytail. She eventually led me off path, into the woods, and there was something vaguely erotic about it, a tugging. The memory of being a teenager, a girl pulling me by the hand from a bush party, away from the bonfire and into the sultry dark, to become invisible bodies among the trees.

And oh, how Connie looked when she turned to face me, as she shouldered the rifle. How she did not hesitate. Her mouth upturned, her eyes – not hard, just clear, certain, confident. Her cheeks flushed from the cold and the exertion of the hike.

One shot, extremely close range, to the face. I had the sensation of being blown backward. I would later conflate the memory with a chewing gum commercial I’d seen as a kid, where a man gets blown out of his shoes by flavour, rocketed out of frame, his empty brown loafers left behind. I was shot out the back of myself like a cannon. Her beloved face, explosive noise, nothingness. I thought, later, that if she’d shot me through the heart or the lungs, or even if she’d beheaded me with an axe, there would have been an in-between, a liminal moment where my eyes were still connected to my brain, still sending signals. Time to look at my ruined body, to see her reaction, see us both splattered with gore. My death felt clean to me, precise, surgical, even though I knew, in reality, it had to have been anything but. Like she knew the pinprick-sized location – above the stem of my spine, behind the Cupid’s bow of my upper lip, in the centre of my brain – where my soul resided, and took it out with a perfect bull’s-eye shot. That’s who she was.

When I woke up on the printer tray at home, I felt no more disoriented than I did in a hotel bed, that moment of dislocation. I padded naked through the house to the master bathroom, showered, dried, dressed. The dark, silent house was what unnerved me. I knew it took twenty hours to reprint me from checkpoint. Had she come home and left on some errand? Had she never come home?

She told me, later, that she made it back to our campsite without encountering anyone, wiped herself down as best she could, changed into fresh clothes. She packed up and drove our car to a motel at the next exit. It was alpine-lodge themed, painted wood with whimsical cutouts and spade-topped fencing that might once have been charming but now had that eerie blend of the childish and the decaying. As she requested a room, she noticed a small streak of blood on her neck in the mirror behind the front desk.

That evening, her hair still dripping wet from the shower, she went down to the attached bar. The place was packed, the tight spaces between tables made tighter by bulky winter coats slung over chairbacks and muddy slush dragged in on boots. She took a seat at the bar that wasn’t really a seat, a barstool wedged in a corner made by the path to the kitchen. Hockey blared on the TV. The bartender threw down a coaster in front of my wife and tilted her head without speaking. My wife got a rye and Coke, not usually her drink. They served food, and she hadn’t eaten since before the long hike, so she ordered the meatloaf. (You hate meatloaf, I said, as she recounted the story. She shrugged. It had been so long since she’d had meatloaf, she explained, she couldn’t remember if she actually disliked it or if that was just something she said.)

—

Excerpted from LESSER KNOWN MONSTERS OF THE 21ST CENTRY. Copyright © 2022 by Kim Fu. Excerpted by permission of Coach House Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Stray Dogs by Rawi Hage

Rawi Hage was born in Beirut, Lebanon, and lived through nine years of the Lebanese civil war during the 1970s and 1980s. He immigrated to Canada in 1992 and now lives in Montreal. His first novel, De Niro’s Game, won the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for the best English-language book published anywhere in the world in a given year, and has either won or been shortlisted for seven other major awards and prizes, including the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Literary Award. Cockroach was the winner of the Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction and a finalist for the Governor General’s Award. It was also shortlisted for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Award and the Giller Prize. His third novel, Carnival, told from the perspective of a taxi driver, was a finalist for the Writers’ Trust Award and won the Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction. His work has been translated into 30 languages.

Stray Dogs by Rawi Hage

During the day, I spent a great deal of time alone, writing and reading. In the evening, it became my custom to join the couple in their garden for a beer or two.

Lukas was an erstwhile photographer. Hannah held a clerical job.

We talked about our lives, politics, books. We exchanged anecdotes and political opinions. Photography was Lukas’s profession, but he also had a long history of “involvement with syndicates,” and in his youth had been a member of a German anarchist group.

One night, Hannah confided that Lukas had lost hope in the world. He had lost his belief in humanity. He talks about his causes, Hannah told me, but their defeat has been too much to bear. The radical in him has diminished, and he’s retreating into himself.

A garden is every warrior’s final objective, I said.

I wish he would go back to photography, Hannah said.

He was happier back then.

Well, I quipped, every hero is a being without talent. I was quoting the Romanian-French philosopher Cioran, but as soon as I realized my insult, I excused myself and rushed back up to my apartment.

Another night, at a party at Hannah and Lukas’s home, a man who looked like Marx—long beard, round face, broad shoulders and belly—approached and asked me what I was writing about. He pulled a handkerchief from his back pocket and patted it on his forehead, then on his cheeks, and finally inflated it loudly with his nostrils.

I said, joking, I am writing about the German soul.

He chuckled, tucked his piece of cloth in his front pocket this time and asked me to explain.

I said, Germans have a distant and cautious approach to strangers, which I prefer to the overly familiar approach to others in French colonial history.

So, presuming the strangeness of others is right in your opinion? he asked.

It allows for curiosity and the possibility of a future dialogue, I replied.

So long as we are curious, he replied, we tend to tolerate. Indeed, I said. Familiarity breeds contempt, to quote the French novelist Stendhal.

You studied French literature?

I nodded and volunteered that my work dealt with how photographic images appear in literature. The man nodded too and took a sip from his beer. You know, he said. He paused before continuing: This is a tight group. So I was not curious about you, I must admit. I was not interested. If anything, I have some hostility towards your type. I am opposed to the money that our government squanders on foreign artists like you, on getting them to come and live here and spend time on their inconsequential bourgeois projects. This money should go to social programmes. You certainly fit the type they go for. Let me guess: you are French-educated, wealthy—and yet here is our government, sprinkling cash on developing-world, privileged sorts like you. I feel that the money spent on you could easily be put to better use. Because of you and the likes of you, our neighbourhoods now are gentrified, and our Berlin is changing. You are either naive or you’re complicit with neoliberal capitalism masquerading as a cultural contribution to the world.

I think you’re partially right about who I am, I conceded. But what does our host Lukas think?

The same, he said. We all think the same here about your kind.

I felt like leaving at that moment, but Hannah, who was watching from across the room, came over and led me by the hand into the kitchen. Let’s have a photo of the three of us, she said, and she pulled Lukas over.

You looked upset, and I wanted to save you, she said in a low voice. Santa over there can be offensive. Don’t listen

to him.

Soon after, I left quietly.

The next day, after my afternoon nap and feeling satisfied with the progress of my writing, I went down to the garden for my customary beer with Hannah and Lukas. I sat down and handed Lukas a bottle. We didn’t talk about the night before. Over time, I had learned that the strength of a closeknit social group lies in its ability to compartmentalize. Lukas asked me what I was up to.

I leave tomorrow for Beirut for a conference on photography, I said. You should come and visit my city sometime.

He nodded and replied, I will.

The conference was to be held at the American University of Beirut. I didn’t expect many people to attend my lecture, as my subject was not directly related to anything overtly political—the Arab world, the Palestinian cause or any such stressful subjects. Instead, my presentation would be on the final passage in James Joyce’s short story “The Dead,” and I knew that exploring the topic of the spatial in the work of James Joyce would be seen as an indulgence, a luxury.

In the last scene of the story, the protagonist Gabriel gazes at a window and describes his memories in a gradual visual movement, evoking a series of photographs that simultaneously detail the spatial and the psychological. We see the window, a lamp, the River Shannon and, at the centre of the montage, the burial site of the young Michael Furey, Gabriel’s wife’s once-upon-a-time lover.

In reviewing this passage, I would emphasize the personal, local and national context of the objects and places we observe, expanding on the mention of the river in this text and in Joyce’s work generally, and simultaneously exploring the idea of the photograph as a subject suspended between life and death. I would allude to Barthes’s aphorism in Camera Lucida that every photograph is an image of what has passed, and I would even dare to say that photography functions as a prophecy of death—overtly linking these observations to the title of Joyce’s story, “The Dead.”

The more I thought about the presentation of my paper, the more I felt that I was ultimately describing a particular suspended existence—my own. And now I felt the temptation to introduce another metaphor: my own identity as a person perpetually suspended between cultures, religions and geographies. But a part of me also hated that narcissism

and opportunism, so prevalent in academia.

After reflecting on this for a while, I concluded that while my work was indeed about ephemerality, it was not about the ephemerality of the self. Rather, it examined the ephemerality of the image of the self. Every hybrid was a partial death, an incomplete acquisition of the original.

The day after the party at Lukas and Hannah’s—the day before I left for the conference—I strongly f elt my state of suspension. All I could think about were the characters in “The Dead,” the woman who had lost her first lover for the incomplete acquisition of another, and the inevitability that she would lose them both.

—

Excerpted from STRAY DOGS. Copyright © 2022 by Rawi Hage. Excerpted by permission of Knopf Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is the author of ten books of fiction and non-fiction, including Motherhood and How Should a Person Be?, which New York magazine deemed one of the “New Classics of the 21st century.” She was named one of “the New Vanguard” by the New York Times book critics, who, along with a dozen other magazines and newspapers, chose Motherhood as a Best Book of 2018. Her novels have been translated into twenty-four languages. She is the former Interviews Editor of The Believer magazine. She lives in Toronto.

Website: www.sheilaheti.com

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

This is the moment we are living in—the moment of God standing back. Who knows how long it has been going on for? Since the beginning of time, no doubt. But how long is that? And for how much longer will it continue?

You’d think it would only last a moment, this delay of God standing back, before stepping forward again to finish the canvas, but it appears to be going on forever. But who knows how long or short this world of ours seems from the vanishing point of eternity?

Now the earth is heating up in advance of its destruction by God, who has decided that the first draft of existence contained too many flaws.

Ready to go at creation a second time, hoping to get it more right this time, God appears, splits, and manifests as three art critics in the sky: a large bird who critiques from above, a large fish who critiques from the middle, and a large bear who critiques while cradling in its arms.

~

People born from the bird egg are interested in beauty, order, harmony and meaning. They look at nature from on high, in an abstracted way, and consider the world as if from a distance. These people are like birds soaring—flighty, fragile and strong.

People born from a fish egg appear in a flotation of jelly, and this jelly contains hundreds of thousands of eggs, where the most important thing is not any individual egg, but the condition of the many. For the fish, it’s less any one individual egg that concerns them than that eggs are laid in the best conditions, where the temperature is most right, and the current most gentle, so the majority might survive. For fish, it’s the collective conditions that count. A person hatched from a fish egg is concerned with fairness and justice here on earth: on humanity getting the temperature right for the many. One thousand eggs are the concern of a fish, whereas the person hatched from the egg of a bear clutches one special person close, as close as they possibly can.

A person born from a bear egg is like a child holding on to their very best doll. Bears do not have a pragmatic way of thinking, in which their favourites can be sacrificed for some higher end. They are deeply consumed with their own. Bears claim a few people to love and protect, and feel untroubled by their choice; they are turned towards those they can smell and touch.

People born from these three different eggs will never com-pletely understand each other. They will always think that those born from a different egg have their priorities all wrong. But fish, birds and bears are all equally important in the eye of God, and it wouldn’t be a better world if there were only fish in it, and it wouldn’t be a better world if there were only bears. God needs creation critiqued by all three. But here on earth, it is hard to believe it: fish find the concerns of the birds superficial, while birds are made impatient by the critiques of the fish. Nothing makes a person feel like their life’s work—or their self—is less seen than when it’s being judged by someone from a different egg.

Yet birds should be grateful that someone is making the structural critique, so they don’t have to. And fish should be grateful that someone is making the aesthetic critique, so they can focus on the structural one.

~

God is most proud of creation as an aesthetic thing. You have only to look at the exquisite harmony of sky and trees and moon and stars to see what a good job God did, aesthetically. So those born from the bird egg are the most grateful of all. Those born from the fish egg are the most upset, and those born from the bear egg aren’t too happy, either.

Perhaps God shouldn’t conceive of creation as an artwork, the next time around; then he will do a better job with the qualities of fairness and intimacy in our living. But is that even possible—for an artist to shape their impulse into a form which is not, in the end, an art form?

~

This particular story concerns a birdlike woman named Mira, who is torn between her love for the mysterious Annie, who seems to Mira a distant fish, and her love for her father, who appears as a warm bear.

~

The heart of the artist is a little bit hollow. The bones of the artist are a little bit hollow. The brain of the artist is a little bit hollow. But this allows them to fly. Those who aren’t hatched from the bird egg might wonder why it was birds—who centre their thoughts on their own selves—who were born to give the world its metaphors, pictures and stories. Why should it have been given to the birds?

A bird can learn to walk on the ground like a bear, and they can spend their whole life walking—but they will never be happy this way. While a fish on the shore gasps for breath, desperate to get back to the sea.

~

How Mira would have loved to have been born of the bear egg! How she would love to be an ambassador of a simple and enduring love, down here on this earth. Yet whenever she sets her heart on such actions, they are wished for, strived for, and barely achieved. To properly love another one—this is the stumblingest part of her, the most nonsensical part, the part of her that is most scattered and always to blame.

But she shouldn’t feel bad about being a bird, for how beautiful are the flowers in her window—the flowers on her windowsill, over there. How their petals and leaves make each passerby smile, that someone loves beauty and cares. Her flowers make us think of the flowers in the soul of the person who put them there. It is the flowers in the soul of the person who put them there that make us happy and enliven our hearts. The beauty of the flowers is a clue to the beauty of a human heart. They are a keyhole into a human heart.

And a fish’s good act, even the smallest action, effectively done, is a glimpse into a human heart. And a glimpse into one heart is a glimpse into many. And the hopes of the bear are shared by all of humankind. And what opens one heart opens many.

—

Excerpted from PURE COLOUR. Copyright © 2022 by Sheila Heti. Excerpted by permission of Knopf Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

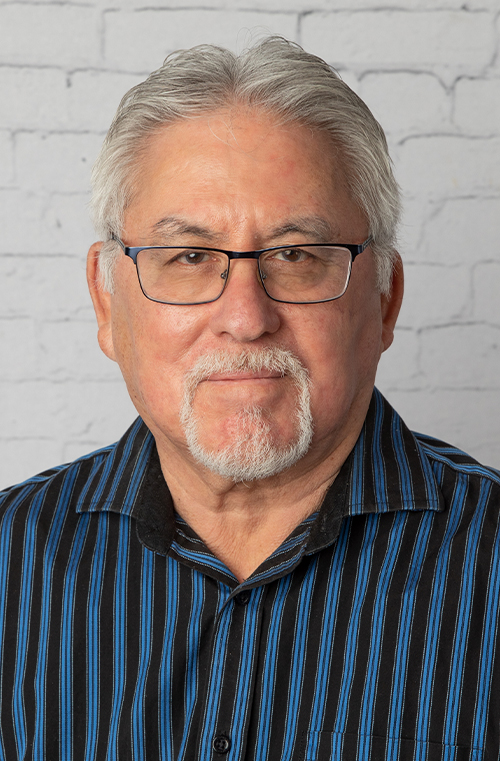

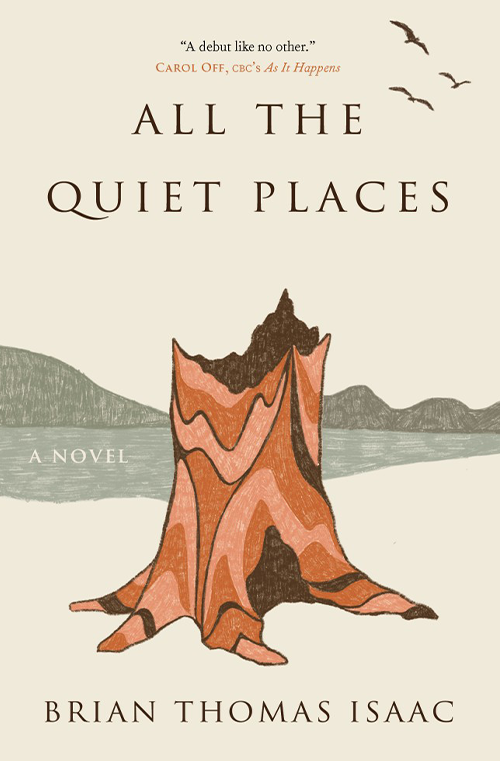

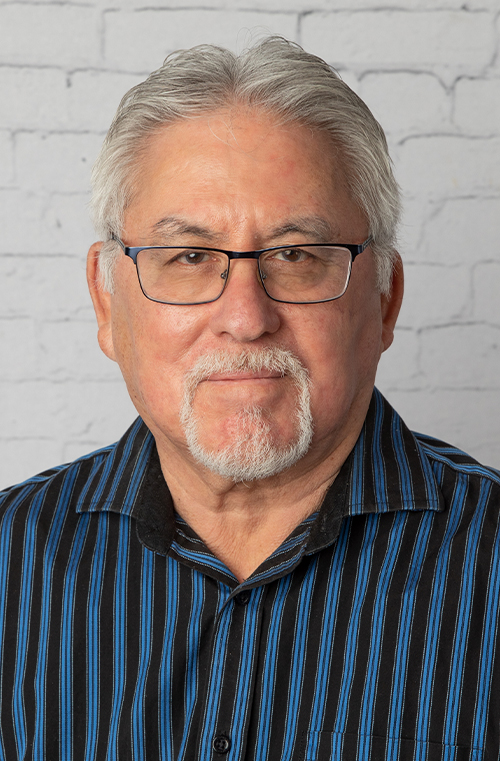

All the Quiet Places by Brian Thomas Isaac

Brian Thomas Isaac was born in 1950 on the Okanagan Indian Reserve, situated in south central British Columbia. As a teenager he rode bulls in rodeos, then went on to work in the Northern Alberta oil fields and retired as a bricklayer. Writing is something he has done all of his life. A lover of sports, Brian has coached minor hockey and slow-pitch teams, and when he’s not spending time with his three grandchildren you can find him on the golf course. He lives with his wife in Falkland, BC. All the Quiet Places is Brian’s first book.

All the Quiet Places by Brian Thomas Isaac

The sultry weather had been building for days until the air weighed on Eddie’s bed like a damp blanket. His feet constantly searched for cool spots on the mattress but never found any. Even the burping frogs down at Heart Lake, a quarter of a mile away, stopped now and then to catch their breath. It was only when cooler air rattled the leaves on the poplars down by the outhouse and swept over the bed that Eddie fell asleep.

A screeching wind jerked him awake. The ceiling and walls cracked and thumped. He sat up. His little brother, Lewis, was fast asleep beside him, and no sound came from his mother’s bedroom on the other side of the paper-board wall. The slop bucket slid across the porch, hit the ground, and rolled banging across the yard. Eddie stood on the bed and looked out the window but saw only pitch darkness. Then lightning flashed across the sky, showing trees that leaned at impossible angles to the ground. With a loud crack a bolt of lightning struck the top of a cottonwood down by the river, and pieces of wood scattered into the wind like dandelion fluff. Eddie saw spots in front of his eyes as if he had looked at the sun.

Lewis woke up crying and stumbled to join his mother, but five-year-old Eddie was drawn to the lightning like a moth to a coal oil lamp. His hand felt the shaking glass with each thunder clap. A nail holding a loose board in a wall squeaked like it was being pulled out by a claw hammer. His mother called to him, and the three of them huddled under her blankets, listening to fir cones and pieces of boughs that hit the roof.

The next morning Eddie let out a long yawn as he stretched and arched his back. He heard water dripping on the hot stove. Psst, psst, psst. He jumped to his feet, and with his nose touching the window, scanned the ground around the house. There were trees down everywhere. The ferocity of the storm had made him think the whole world had been flattened, but it wasn’t as bad as he had imagined. Everything always looked better in the morning anyway. A squirrel ran along a trail of broken branches. Noisy birds chirped and swooped. Nuthatches flitting about on the roof of the outhouse were frightened away in a flutter when a robin landed among them.

Eddie jumped off the bed and was about to walk into the kitchen when he saw his mother at the table. Grace sat perfectly still, and a thin line of smoke from the cigarette in her fingers reached up to the ceiling like a string. The long ash on the end looked ready to fall, and the red glow was so close to her skin that Eddie wondered if she was getting burned.

Sometimes he found her sitting this way, red-eyed, quiet and still. He felt sad and wondered what he could do to make her feel better. She didn’t move when he pulled out a chair and only looked at him when his knee bumped the table leg.

Grace sat up and looked around as if she had been caught daydreaming. After snuffing out her cigarette, she filled a bowl with porridge from a pot on the stove. With a big spoon she scooped out a red glob of jam from the large can in the centre of the table and dropped it into the bowl. She slid it across the table to Eddie. Sitting back in her chair, she looked out at the downed trees.

“Looks like I’ll have to sharpen the Swede saw,” she said. “We’re going to have to cut up all that wood and pack it up to the shed before it starts snowing. Seems like it might be enough for the whole winter. And you have to go on the roof and fix that new hole. Don’t know how many shingles are missing.”

The thought of all the work made Eddie push his bowl away with his elbow and rest his head on his arms. That was when he noticed a dark form moving among the trees down at the edge of the clearing close to the river. He sat up and looked through the cracked kitchen window. The slightest movement of his head made the image drift away and back again. He felt a chill as if someone had run a finger lightly up his back.

Whatever he had seen—bear, deer, or moose—was down close to the river at a piece of land where his mother, grandma, and uncle had cleared away the brush for a garden large enough for the two families. They’d stopped when they found that just under the top layer of soil was a thick layer of roots. It wasn’t long after the work stopped that the ground became choked with Oregon grape.

When Eddie’s mother stepped out of the house and strolled down the trail to Grandma’s, he looked over to the wall where the .303 rifle rested on bent spikes. He stared at the gun for a long time. Grace always told him there were three things he’d better not do until he was older: make a fire in the bush without her, go down to the water by himself, or touch the gun.

—

Excerpted from ALL THE QUIET PLACES. Copyright © 2021 by Brian Thomas Isaac. Excerpted by permission of Brindle & Glass. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

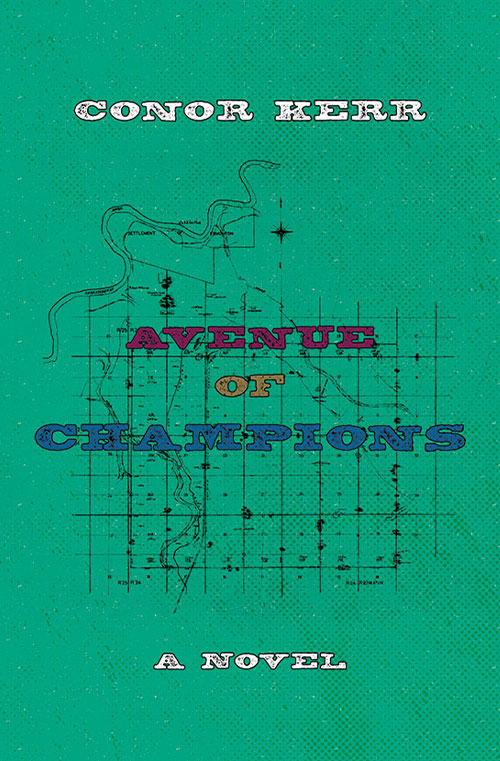

Avenue of Champions by Conor Kerr

Conor Kerr (he/him) is a Métis/Ukrainian educator, writer and harvester. He is a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta, part of the Edmonton Indigenous community and is descended from the Lac Ste. Anne and Fort des Prairies Métis communities and the Papaschase Cree Nation. His Ukrainian family settled in Treaty 4 territory in Saskatchewan. Conor works as the Executive Director of Indigenous Education & Services at snəw’eył leləm’̓ (Langara College) and lives in Vancouver on the unceded territories of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam First Nations. In 2019, Conor received The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Poetry Prize and in 2021, The Malahat Review’s Long Poem Prize. His writing has been published widely in literary magazines and anthologized in Best Canadian Stories 2020 and Best Canadian Poetry 2020. His first two books were published in 2021: the poetry collection, An Explosion of Feathers and debut novel Avenue of Champions. He has a forthcoming poetry collection tentatively titled Old Gods for publication with Nightwood Editions in 2023.

Avenue of Champions by Conor Kerr

Granny and her husband were both little kids when the Canadian government dissolved the Papaschase First Nation. All the Band members had been off hunting or at the Fort and the mounties and the Indian agent took advantage of that and declared the First Nation null and void. When her family tried to go back to their shacks to get some supplies, the mounties were already there and everything was up in flames. Granny fled with her family to the bush north of St. Lina, Alberta. She lived there, married a man from the Papaschase whose family also fled to the bush. The two of them started having kids, but then Granny’s husband up and died one day. My mother told me he died from heartbreak from being forced off the land he had loved. Uncle Jim told me it was tb. Either way, Granny never talked about her husband. And she never talked about the Papaschase land she had grown up on. But she loved woodpeckers. Anytime a woodpecker would be hanging around the cabin she would spend all day rolling handmade cigarettes, drinking tea and watching the bird work its way around a white poplar tree.

Uncle Jim showed up back at Granny’s cabin a few days after I turned fifteen. He had spent a year after the war “showing those Québécois ladies how to really jig.” Then he had run out of money and hopped a train back out to Alberta. When he first arrived, we’d sit around Granny’s cabin night after night and listen to him tell stories about Europe and the war. Everyone who was anyone plus a few others from the area would be over at Granny’s drinking ’shine and listening to Jim describe how the underwear looked on this lady from Trois-Rivières.

“You watch out, she might be your cousin,” Granny would yell, smiling with a cigarette hanging out of her mouth as she ladled out drinks for the listeners. That summer was a real party. We went through more ’shine than we had in a long time, partly because of the nightly story session, partly because Jim drank it all day every day.

Even if Uncle Jim drank the still dry the night before, he would be up for the sunrise. Didn’t matter if the sun was coming up at 8:30 in the winter or 4:30 in the summer, he would rise with it. I woke up every morning to the thwock of the axe splitting birch from the wood pile. The smell of tobacco trailed behind him as he walked past my bed carrying an armful of wood for the stove. I always tried to wait until the stove had the cabin roasting before I got out from underneath the wool blanket.

The morning after Jim fell through the ice on the Amisk River he was moving like a bear with an itch. After the stove got fired up, I could sense him standing right above me, but I refused to open my eyes, hoping he would get bored and wander off to check on the stills. He poked me in the gut with the barrel of the 30-30 lever action rifle we kept by the door.

“Hey girl, those beavers are probably dragging some kid under the ice right now.” He poked me again with the barrel of the gun. “Might even be one of your brothers or sisters.”

“Get out of here, you reek like booze you old bum.” I turned over and pulled the woollen blanket over my head. “That thing better not be loaded.”

“How would you feel about that?” Jim said.

“Don’t really care.”

He wasn’t going to leave me alone. The stove had taken the frost out of the air in the cabin. Jim sat on the chair across from my bed and started rolling a cigarette.

“Roll me one of those and I’ll help you out,” I said.

Jim finished rolling a smoke and passed it to me. Then he started rolling another one for himself.

“I found the spot. Ain’t no more beavers going to be dragging poor unsuspecting folk under the water any longer.”

We saddled up the wagon horses. They both snorted and stomped their appreciation for going for just a little ride and not hauling the wagon around. Granny walked by us on her way down to the still. She nodded at us, the customary cigarette hanging out of her lips unlit until she finished her walk. Granny never smoked while walking.

“If you see a moose, take that instead of the beavers. We could use the meat,” she said.

Jim gave a faux salute and we set off through the bush. It was a good dozen miles or so to the spot on the river where Jim had gone through the ice. I settled into the saddle and lit the cigarette Jim had rolled for me. The sun had a warmth to it that we hadn’t felt in months. All around us the land was waking up from its winter rest. Birds chirped and fought between the bare branches of the poplar and birch trees, squirrels chattered to announce our arrival as we passed underneath them on the trail, a couple coyotes howled in the distance. The worst of winter was behind us and everything in the bush was out in full celebration. Even Jim seemed to momentarily forget that he had a score to settle with some beavers.

The melting snow had left a series of cracks through the ice on the Amisk River, and you could clearly see the spot where Jim had fallen through after the party. There was a thin layer of ice over the hole and in the busted-up area where he had been dragged out. Whisky jacks swooped all around us checking out what we were doing in their area, their grey and black feathers bristling with the prospect of a free meal.

“awas,” Jim yelled at them, then muttered, “You’re giving away our goddamn position. Damn beavers will know we’re coming now.”

“I think the yelling gave us away, not the whisky jacks,” I said.

“No one cares what you think,” Jim grumbled and pulled a jar of hooch out of his saddlebag. “Shouldn’t be too shooken yah think?” He took a big swig.

“Not many beavers around here,” I said.

“Oh they’re coming, believe me, those toothy motherfuckers are coming.”

—

Excerpted from AVENUE OF CHAMPIONS. Copyright © 2021 by Conor Kerr. Excerpted by permission of Nightwood Editions. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

Tsering Yangzom Lama holds a BA in creative writing and international relations from the University of British Columbia, and an MFA from Columbia University. Born and raised in Nepal, Tsering has lived in Toronto, New York City, and Vancouver, where she now resides. We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies is her first novel.

We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

Pokhara, Nepal

Summer 1962

By sundown, they tell us, we will reach our sixth and final camp. Five rented buses have driven our group as far as the roads and riverbank would allow, and now we are on foot, walking in a deep river gorge, our steps and sightlines hemmed in by an endless procession of hills. The trail is narrow, so we walk in a long, slow line, all four hundred of us gathered from various border towns. Ahead, Ashang Migmar and Po Dhondup carry our possessions, their heavy sheepskin coats hanging from their waists, while I carry Tenkyi on my back. Like so many in our group, my little sister is unwell and too weak to walk. At least she’s still with us. In Baglung, we heard that our aunt, Shumo Yangsel, and her husband had been there for several weeks before our arrival. They had begged for food on the side of the main road, telling anyone who passed by that their children were waiting in the mountains for help. Ashang thinks Shumo’s sons must not have survived the journey out. He wants to find her, his little sister, and keeps asking the two foreign aid workers who rented the buses about her. But they don’t know anything about Shumo’s whereabouts. All they can tell us is that we’re heading to the camp, our new home, they call it. A message passing slowly, in pieces, from their tongues to ours.

But where are they leading us? I had thought in Mustang that we had reached the lowlands, but here, with this heavy air, we can hardly breathe. It frightens me to think that the earth could keep falling down and down like this. Meanwhile, the sun grows hotter in each place we go, as if to light us all on fire. Yet in the corner of my eyes, behind these dark hills, I can see a line of mountains, white and silver, even more luminous than the sun. As I take these steps, I think of home, where we don’t have roads. Where we walk any place we wish, across the grassy plains, along the wide gentle hills.

Half a day has passed without food or water. We have become a silent line of bodies that traces the unceasing river to our right. My lower lip cracks and bleeds from thirst, and as I lick its rough surface, I peer down over the edge at a river that taunts me with its waters. If I go down for a drink, I doubt I could manage to climb back up this cliff.

Finally, at sunset, we hear foreign chatter. The aid workers ascend a small hilltop and pull out some papers. Then they drop their bags and move out of view.

“This must be it!” someone shouts behind me.

Gripping onto bunches of grass, we clamber up the hill to see the land. Even Tenkyi is on her feet now, walking to the top of the ridge. As we look out on a small clearing of hard earth and few trees, I clutch her hand.

Ashang kneels and rubs the soil with his fingers. “Nothing will grow here,” he says. “With this kind of earth, the milk will be thin. The butter will be pale.” How, he wonders, can we raise animals, or have any measure of space in this narrow plot of rocks? How, he whispers, can he call himself a nomad? A nomad would never pitch his tent on such barren land.

But no one says a word to the foreigners. We hear that they have paid the Nepali government for this bit of earth. They have also made prom-ises to local villagers to give them water pumps and more so that our group of four hundred or so refugees, as we’re now called, can stay here. On this hilltop, we must make a new life.

—

Excerpted from WE MEASURE THE EARTH WITH OUR BODIES. Copyright © 2022 by Tsering Yangzom Lama. Excerpted by permission of McClelland & Stewart All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr

Suzette Mayr is the author of the novels Dr. Edith Vane and the Hares of Crawley Hall, Monoceros, Moon Honey, The Widows, and Venous Hum. The Widows was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book in the Canada-Caribbean region, and has been translated into German. Moon Honey was shortlisted for the Writers’ Guild of Alberta’s Best First Book and Best Novel Awards. Monoceros won the ReLit Award, the City of Calgary W. O. Mitchell Book Prize, was longlisted for the 2011 Giller Prize, and shortlisted for a Ferro-Grumley Award for LGBT Fiction, and the Georges Bugnet Award for Fiction. She and her partner live in a house in Calgary close to a park teeming with coyotes.

Instagram: @suzettemayr

Website: www.suzettemayr.com

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr

He delivers the pairs of shoes as he completes them, slides them back under curtained berths, opens the individual lockers and shoves them in, toes to the front, heels to the back.

He blacks boots, polishes, he buffs, he polishes again.

Edwin Drew once told him and a group of other student porters a story about how one time he collected all the shoes from a car full of passengers, and then when he went to return the shoes, saw that the passengers’ car had uncoupled from the rest of the train when the train stopped at the last station, and that he now had a bag full of shoes and no passengers, and the passengers had no shoes.

Baxter and the other greenhorns shuddered with laughter, Edwin Drew grabbing Baxter by the arm to hold himself up as he guffawed, and Baxter feels buttery inside at the memory, at the glowing warmth and strength of Edwin Drew’s grip through his sleeve.

As he returns the pairs of shoes one by one, the fact that he doesn’t have enough brown shoeshine to last out this run picks at the back of his head. Eugene two cars over might have extra brown shine. Yes, he can ask Eugene for some brown shoeshine. He will brush aside Eugene’s childishness, his sulkiness. After all, as porters they are all brothers, Eugene chattering on about the Brotherhood.

Once upon a time Eugene still treated Baxter like one of his own: he taught Baxter new card games whenever they met up at porters’ quarters, then he’d lick him at the exact same card games. He joked with Baxter like a little brother about the books Baxter read, how his nose was always in a book or a magazine and he seemed to like books better than people.

– Maybe if you weren’t reading so many weird books you’d find yourself a wife, Martian! Eugene would say. – Har har! Pass me that deck of cards. I have another game I can teach you to lose.

Eugene fanning the cards out on the table between them, his straw sailor hat perched toward the back of his head, his bony fingers and wrists flicking and dancing in the air as the cards fell in precise, geometric formation.

– Nothing wrong with being from Mars, Baxter would say, and Eugene would just snicker, – Sure, Martian.

Then, after the Edwin Drew matter happened, Eugene started making a face like Baxter was a charred piece of meat whenever he saw Baxter. Suddenly. Sadly. Baxter never knew who told Eugene; it could have been Eugene’s sister, Edwin’s wife. Or Edwin himself.

Edwin would never do that.

Baxter passes through the vestibules between their cars and almost trips over a pair of men’s shoes sprawled in his way, the shoes polished so hard the uppers mirror his face. Before he touches them, his face and fingers reflected back oblong and jagged in the leather, he realizes the soles glow like embers, they don’t belong to anybody on this train, and so he steps over them so they won’t contaminate him. No one else will bother with or even notice figmental shoes like these.

He worries that one day the lack of sleep will drive him into the lunatic asylum.

At first Eugene pretends not to hear Baxter as he buffs and turns a shoe, his elbows pointed out too far, then drops it next to its mate, his feet buried in multiple pairs of passengers’ shoes, exactly the way porters are not supposed to do it.

– Got none to spare, says Eugene. His mouth flattens into a disappointed slice. Baxter’s chest contracts. Eugene has the longest eyelashes Baxter has ever seen on a man.

Eugene’s call board chimes, and he tosses the shoe back into the pile. He unfolds his stick-figure self up from the stool, one limb at a time, not hurrying one bit.

Baxter retreats from the doorway as Eugene pushes past him.

Baxter returns to his car, the ground rocking as he moves. He’ll ask the freckled porter to watch his car.

—

Excerpted from THE SLEEPING CAR PORTER. Copyright © 2022 by Suzette Mayr. Excerpted by permission of Coach House Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga

Noor Naga is a writer who divides her time between Cairo, Alexandria, Toronto and Dubai. She has family in each of these cities and feels she belongs to them equally. Apart from her debut novel If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, she is also the author of the verse-novel Washes, Prays, published by McClelland and Stewart in 2020.

Twitter: @noor_naga

Facebook: /noor.naga

Website: noornaga.com

If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga

Question: If you are competing to lose, what do you win if you win?

He told me he was from a village, Shobrakheit. He told me a New Yorker and a Cairene have more in common than a Cairene and a man from Shobrakheit, but he would not tell me what the commonalities were. Instead he asked if I had ever ridden a microbes, and I was forced to say no. What about a tuktuk? Another no. And then I remembered that when we’d stopped at the kiosk for cigarettes, he had bought singles. I looked and seemed to see him for the first time: the hems of his pants were frayed, strings dangled from his vest like lines of saliva, yet he wore a perky bow tie. He wore black leather sandals with socks, but one of the soles was loose, flapping like a bottom lip when he walked. I didn’t know then: every night before bed he washes his feet and socks in the sink, wrings the blackness out of both. Hangs the socks on the bathroom door handle to dry for the morning. Only pair he has. He washes his socks every night but he has never brushed his teeth with toothpaste or shampooed his hair. Does not own deodorant. If he showed a little more ideology, he could be considered woke— some kind of minimalist, an ecofreak. How to say consumerism in Arabic? How to say toxins, microplastics, mutagenics, fair trade, ethical sourcing? But the boy from Shobrakheit doesn’t give a reason for not shampooing his hair— just says he doesn’t like to. What’s a hipster without intentionality? Old- fashioned and proud and poor. Also, Egyptian. More than anything, what binds people here to one another here is the pointless struggle for quality of life. I’m learning slowly that having money and the option to leave frays any claim I have to this place. It turns out that to be clean in Egypt is just to be free of Egypt, to exercise the choice to stay or go elsewhere, which most of the population cannot do. The boy from Shobrakheit will die never having crossed a border. He is so tall that when we walk around downtown at night, his hair catches on the butchers’ hooks, which are black- tipped, yanking, the blood beneath them never dry. He took me to get liver sandwiches from a cart on the street, but not the popular cart. The popular cart is a pound more expensive per sandwich, which is robbery, he said. We sat on the sidewalk to eat, and I knew he had chosen the ground because I had chosen the crème slip- dress, which would catch the dust like a wet tongue. But I take the metro all the time, I said, remembering that I had ridden it once when I first arrived and that it had cost as little as a pound, as little as six cents American. We test each other.

—

Excerpted from IF AN EGYPTIAN CANNOT SPEAK ENGLISH. Copyright © 2022 by Noor Naga. Excerpted by permission of Graywolf Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

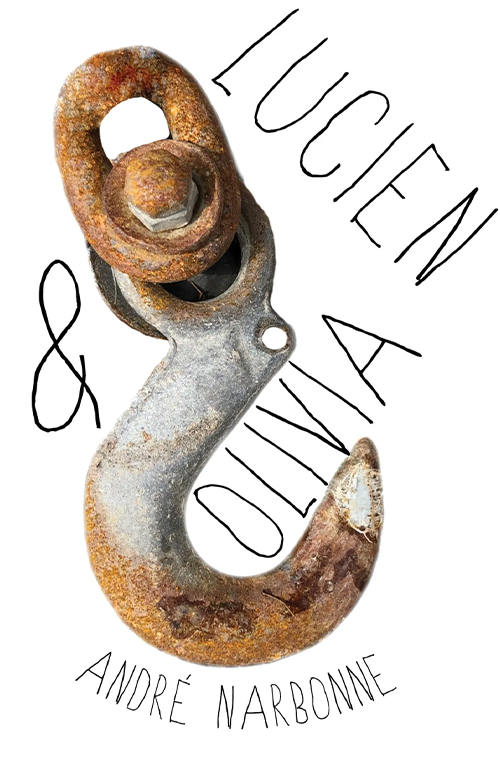

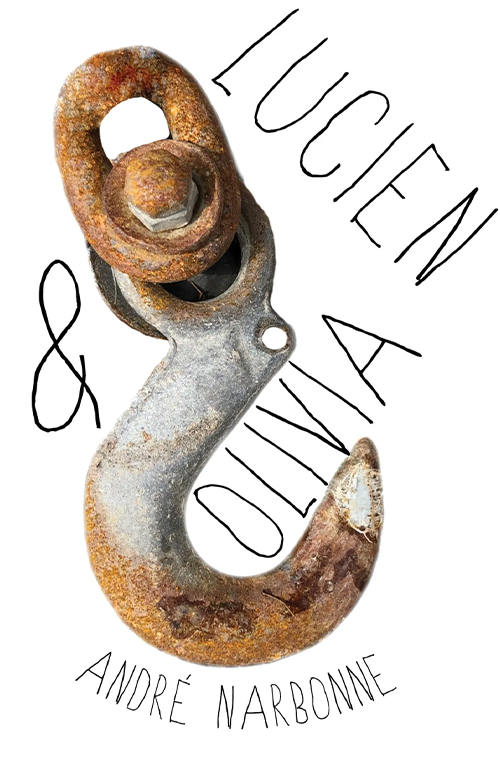

Lucien & Olivia by André Narbonne

André Narbonne is the father of four children and the author of three books. He teaches at the University of Windsor where he is the reviews editor of the Windsor Review. His critical and creative writing has seen publication in nearly one hundred North American journals, been anthologized in Best Canadian Stories, and won the Atlantic Writing Competition, the FreeFall Prose Contest, and the David Adams Richards Prize. A short story collection, Twelve Miles to Midnight, was a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Literary Award. A poetry collection, You Were Here, was published by Flat Singles Press in 2016, and his first novel, Lucien & Olivia, was published with Black Moss Press in 2022.

Lucien & Olivia by André Narbonne

Off New England, the ship rolling more perilously than before, like a pendulum bound to no specific rhythm.

On watch, Lucien ties the engine room fridge with its single carton of milk for the coffee to a bulkhead to stop it from roaming the deck, to stop it from smashing into the turbines or into Harry, who sits with a bucket in his lap in a chair tied to the opposite bulkhead. He returns to his cabin at noon to find his Walkman smashed on the deck, shouts, “Fuck!” at the overhead as he tosses it into a drawer. He is usually more circumspect, more in tune to seaboard gravity, but something about the journey—Halifax?—has thrown off the sea instincts that generally stay with him into his relief. When he gets home he’ll unpack with a mind for stability, shoring clothes against the potential pitch of the house. When they first started together Sylvia would laugh when, the first few meals at home and in restaurants, he pushed condiments to the centre of the table to give himself time to react to shifts in gravity.

The next day the waters are still, yesterday’s tempest, a seeming clerical error, the ocean blue-getting-bluer. The horizon is boundlessly empty: no ships, no shore, no clouds.

From stem to stern, finger length bodies asphyxiate on the hot steel, flying fish. The deck is alive with their grotesque struggle. He picks one up and holds it to his nose, throws it back, doesn’t notice he’s being watched until the third mate says, “You can’t save them all. They’d hop another ship anyway. Nice bit of Darwinian mismanagement. Evolution hasn’t taken us into account.”

The mate is a short, thick, balding man whose solitary fashion statement, John Lennon glasses, are a curious fit with his bulbous nose, making him look like an accountant. Likely he’s invisible on shore. His is an invisible look. On the Douglas he sleeps behind a locked door—the only crewmember to do so. No one knows what he fears, so the galley is rife with rumours.

Harry emerges from the after house with a sausage in one hand, a cup of coffee in the other. The bosun follows with a grapefruit and a copy of The Atlantic. The bosun is a lapsed chess master, who played professionally before becoming a sailor. Nights when they play chess, Lucien arrives with a bottle of gin. The bosun, an exceptionally easy drunk, marvels that he can never beat Lucien.

Harry rubs his hair sleepily, yawns, and says, “Where are we?”

“South of the Carolinas,” answers the mate.

Harry scans the absence of horizon, looks out into a blue that must be two blues meeting somewhere, and says, “Creepy.” He bites into the sausage. “This is a different kind of alone.”

The mate spanks the rail. “Are you studying to be an engineer or a poet?”

The bosun says, “Speaking of poets, there’s this Shelley bit that I think speaks to what Harry feels: A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear and…drowsy, unimpassioned grief, in its…starless lake of blue.” He bites into his grapefruit and everyone else grimaces.

Folding his arms on his chest, the mate says, “Yeah.” He kicks a fish. “That’s what I was going to say.”

*

Rounding Florida, the heat-held days transform the engine room into a shuddering crematorium. Harry spends whole watches with his head pushed up a fan duct. Jon, whose shirt caught fire when he was five and he misplayed with matches, chafes at the skin grafts peeking out of his collar. Lucien reminds himself not to work. The risk of passing out is too great. Spend the watch watching.

Suppers are gross. He can’t keep the sweat out of his food. But the waters are calm, the colours as they steam into the Gulf, paradisiacal. The ships now appearing regularly on the horizon are giants. Texaco supertankers dwarf the Douglas, making the contract seem surreal. What use has Texas of Canadian oil?

They arrive on the seventh day out to a Port Arthur refinery at the end of a swamp. Are warned by the shore crew to be on watch for alligators. Lucien stays onboard. Off watch, Harry keeps him company playing euchre.

“Don’t you want to say you’ve been to Texas?” Lucien asks him.

“I’m in Texas.”

“Doesn’t count until you step ashore.”

“It does.”

“The ship’s not a place.”

Harry shrugs. “Who do I know in Texas? I’d rather hang out with you.”

“You understand that shipboard friendships don’t last? They’re situation specific. You may never be in Texas again. You should be ashore buying a spoon. Years from now, you’ll be able to say over crumpets that you were in Texas.”

“The reason our games take so long is because you always talk when it’s your turn to deal. Have you noticed that every time you ask me whose deal it is, it’s yours?”

*

Canada-bound the next day, the Chief tells Lucien he’s received word from head office that his relief is hired. He’ll be on the dock at the next port or maybe in the canal depending on where the contract takes them next.

Time drops off a cliff. Lucien is impatient with simple tasks, hardly speaks with the crew. Over three years working together he’s developed a work-rhythm with Jon, who recognizes the signs of his abandonment when he sees Lucien staring blankly at the control console, a bank of twenty-three sightless brass gauges staring back.

“You’ve got it something terrible,” he says. “Channel fever. I doubt I’ve seen it so bad.”

“I know.”

“Don’t worry about the watch. You just do what you’re doing.”

“Thanks.”

Steaming past New England Lucien stops speaking on watch. He’s silent in the galley and the rec room. At the mouth of the St. Lawrence Jon has had enough.

“You’re killing me. I don’t care what—say something. What are you thinking about?”

“I’m thinking about the Halifax Explosion. Do you know about that? It was 1917, the end of the First World War was in sight, and two ships collided in the harbour, wiping out the North End.”

“Yeah, I know about it.”

“The Imo was Norwegian; the Mont Blanc, Belgian.”

“Okay. That’s a start. What are you thinking about that?”

“I’m thinking the crews spoke different languages, but the ships had the same engines, triple expansions, so the engine room crews were saying the same things just with different sounding words. They were having the same day. Before the ships blew up.”

“Okay. That’s good,” says Jon, “Do you want a coffee?”

“I don’t know.”

“Fuck.”

—

Excerpted from LUCIEN & OLIVIA. Copyright © 2022 by André Narbonne. Excerpted by permission of Black Moss Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Hotline by Dimitri Nasrallah

Dimitri Nasrallah is the author of four novels. He was born in Lebanon in 1977, and lived in Kuwait, Greece, and Dubai before moving to Canada. His internationally acclaimed books have garnered nominations for CBC Canada Reads, the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and the Grand Prix du Livre de Montréal, and won the Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction and the McAuslan First Book Prize. He is the fiction editor at Véhicule Press.

Hotline by Dimitri Nasrallah

At five minutes to two, I check my face in the mirrored walls of the building’s lobby, straighten my blazer, touch up my lipstick, and then board the elevator to the sixth floor. I’ve been through this process many times now. I’m always hopeful that this time will turn out differently. Inshallah! I’m already finding things to like about this building: the lobby is bright and well kept; there’s a security desk to keep out all the abu reihas from doing drugs in the public washrooms; even the elevator is a good size. I know myself. I grow attached to little touches like this too fast, and I begin to imagine myself anywhere and everywhere in an effort to will the world to bend my way for once. I’m a dreamer. My mother always said so.

The elevator doors open at the sixth floor, where a promising white lobby and relatively clean carpeting greet me. Someone has thought to empty the large ashtray garbage can by the elevator so it’s not the first smell to backhand you when the doors slide open. Along the wall to the right is one of those modern-looking glass doors, and stencilled across it in neon-red letters is the name NUTRI-FORT.

I step inside and announce myself to the bored receptionist. “Muna Heddad,” I say. “Here for the information session. We spoke earlier.”

She rolls her eyes, checks her list, and then points to a room down the hall. “Follow the signs for Information Session and wait with the others. Help yourself to the free coffee.”