[Video] The Giller Book Club: What Strange Paradise

[Video] The Giller Book Club: What Strange Paradise

January 12, 2022

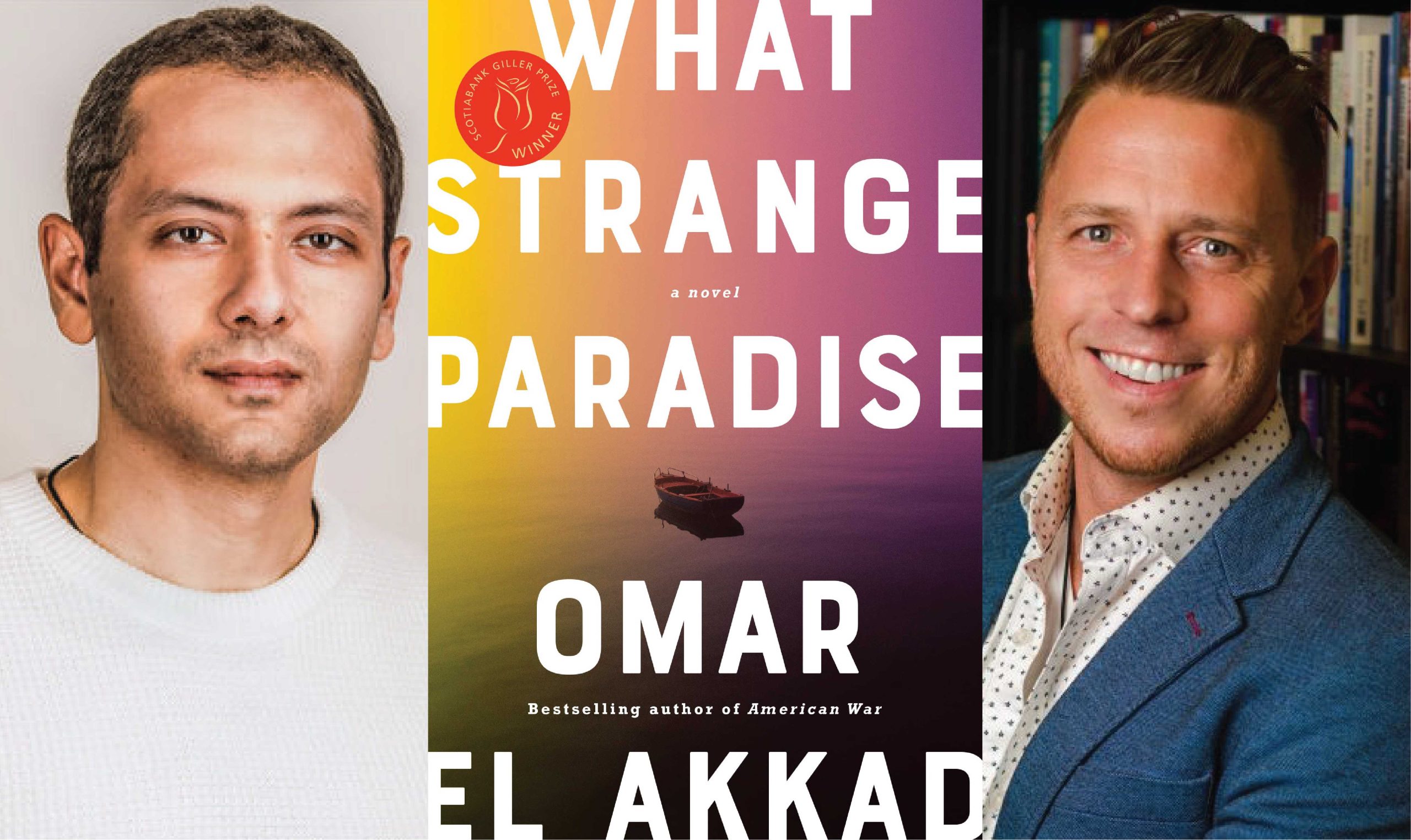

Daphna Rabinovitch 0:00

My name is Daphna Rabinovich, and I’m thrilled to welcome you to the first Giller book club for 2022, our second year of doing virtual book clubs. This year we will host 11 book clubs from now until the end of June. Please check our website for the complete list and to register every month you really don’t want to miss a single one. And please make sure to have your Zoom on a side by side view for the best possible experience. Tonight, it is my profound pleasure to introduce you to our interviewer Sam McKegney. Sam is a settler scholar of indigenous literatures as well as being professor and head of the English department at Queen’s University in Kingston. His teaching and research seek to register the ways in which indigenous literary artists interrogate ongoing settler colonialism, imagine modes of sociality, that exceed the confines of the settler state, and provoke extra textual responses from indigenous settler and diasporic readers that might contribute to decolonization. He is the author of two monographs concerned with indigenous literary art, and the editor of a collection of interviews on the subject of indigenous masculinities. He is also a founding member, member, excuse me, and past president of the Indigenous Literary Studies Association, and the principal investigator for the Indigenous Hockey Research Network. Tonight, Sam will be interviewing Omar El Akkad, winner of the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize for his amazing and riveting novel, What Strange Paradise. There will be lots of fascinating questions and a reading. And if you’d like to ask a question, please feel free to submit one using the q&a button at the bottom of your screen. So I don’t want to waste any more of your time I’m not the main event. Please welcome Sam and Omar.

Sam McKegney 2:12

Thanks so much Daphna. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m zooming in from my office at Queen’s University, which occupies lands of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe peoples and it’s my honor to introduce you to the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize winner Omar El Akkad, a writer whose muscular prose is alive with vulnerability, and who crafts lines of such power that it’s difficult to imagine a time before one read them. They seem to have always existed awaiting one fluent enough in life’s brutal magic to decode them onto the page. The worlds he creates surgically precise are immersive. They take the reader utterly away, and yet they are of this place, teaching us about ourselves and our responsibilities in a fraught world. I say this because I believe him to be among those rare writers who can genuinely spur his readers to understand themselves differently, perhaps even to change. El Akkad is an author of novels, short stories, investigative journalism and social commentary. He’s won a national newspaper award for investigative journalism and the Goff Penny Award for young journalists. His award winning debut novel American War is an international bestseller and has been translated into 13 languages. His most recent work What Strange Paradise upon which will focus our conversation today, tells the story of A,or a nine year old migrant, the lone survivor of an overfilled, ill equipped and dilapidated ship, sunk under the weight of its too many passengers and Vanna, the teenage girl compelled to responsibility for this complete stranger whose humanity she refuses to deny. As tender as it is unflinching as captivating as it is artfully rendered, What Strange Paradise is in the words of author Union, Lee, imaginative, touching and necessary. I’m also thrilled to share with you that El Akkad is a graduate of Queen’s University where he studied computer science and took his first creative writing courses with our dear mutual friend, the esteemed author Carolyn Smart. He is returning to Queen’s this term as our English departments 2022, Writer in Residence, it’s great to see you welcome.

Omar El Akkad 4:26

Thank you so much for doing this. And thank you for that incredibly generous introduction. That was that was far more kind than I deserve.

Sam McKegney 4:34

I disagree. I think you deserve it immeasurably. I was thinking that perhaps I’d start with some questions about craft and process and, and motivation and things like that, and then we can move into discussions of the novel if that works on your end.

Omar El Akkad 4:49

Sounds good.

Sam McKegney 4:50

Okay, so I mean, the first question for me always is why writing? What is it about literary art that captures your imagination? When did you know that this was going to be the direction that your life would travel.

Omar El Akkad 5:03

I was five and a half. I was at the American International School in Doha, Qatar. Out in the Middle East. The school newsletter that week was the anti littering edition of the school newsletter. I wrote a short story about why you shouldn’t litter, they decided to publish it. And I was hooked. That was it was the, the beginning of it for me. I mean, I always try to find graceful ways of getting around the reality that, you know, it’s writing because I’m not good at anything else. This is the only thing I’m sort of halfway decent at. But, part of it has to do with the idea of, of, you know, I often say that I’m one of those people who doesn’t have a very good answer to the question, Where are you from? You know, I left, I was born in Egypt, my family’s Egyptian dating back many, many generations. But I left Egypt when I was five. And then I grew up in Qatar, but I was never going to get country citizenship, they want to protect the oil and gas wells, so they don’t hand out citizenship. I am a citizen of Canada, but I moved there when I was 16. Canada doesn’t start for me as a personal experience until until 16. Now I live in the US, but I thought I understood this country and every morning, I wake up and realize that I don’t in the slightest. And my suspicion is that for people like me who don’t, don’t have a set of routes, or a singular set of experiences that they can point to and say this is mine. Fiction ends up being a very comforting place, you can sort of alter the contours of your made up world to fit the contours of your own experience. I think that’s probably what drew me into it. And you can sort of see hallmarks of that in a lot of my fiction. The short stories and novels, all of it, where one of the earliest things I do is sort of show this very overt disrespect for geography and the nation state and geopolitics, I, I move borders around, and I do all of that stuff and I think part of it is because fiction allows me to do that. So I think that’s probably why I gravitate towards it. That’s not to say that I’m any good at it. It’s just, it’s just the draw, there’s something magnetic about being able to go to that part of your brain where you don’t have to worry about having a very neat answer to the question, where are you from?

Sam McKegney 7:29

That’s such an interesting way of framing it because I consider your work so meticulously realist in certain ways, even as it’s doing what you’re suggesting, right, with that disrespect of the nation state with moving borders around with changing geographies and building fantasy. And are they are those two processes entwined for you of the fantastical and the realist?

Omar El Akkad 7:56

I think so. I mean, I, you know, you mentioned that I had gone to Queen’s, and that my degree is in computer science, I can’t program my way out of a paper bag. I’m th,e Queen’s should not have given me that degree, it was very kind of them to do so. But I, my education at Queen’s was at the Queen’s Journal and the Golden Words and at the student magazines, and you know, that sort of thing. In fact, I don’t know if this is still the case. But I think to get into honors year, year, four of your degree at Queen’s, you need to have a cumulative average, I think of like 65. And it’s your core courses and your best electives. And I got in with a 65.3 because all my creative writing electives were so high that they kind of just slowly like lurched me over the the cutoff to get that degree. I, the education I got after Queen’s was at the Globe and Mail, I spent 10 years as a journalist. And it was a very particular kind of education. You know, my first day there, Greg O’Neill the dean of the back desk at the time, he passed away a few years ago, but he’d been there for about 40 years, when I showed up. He used to sit down every intern and say, listen, here’s what you need to know about this newspaper. Over here all the reporters are gods but all of the editors are atheists. And it was his way of explaining to you what they were about to do to your copy. You know, if you put in one too many adjectives if you got a tiny bit too purple, did any of that stuff, they were going to slash it left, right and centre. So 10 years of that really tightened up the style. I mean, if you read American War, particularly the first half of American War, that’s a pretty purple first half of the book. I mean, I assert, and that’s after 10 years of having that sort of like beaten out of me by my back desk editors of The Globe. So you can only imagine what it was like on the other side of that. I do think the experience of writing nonfiction professionally, writing journalism professionally for 10 years, works its way into into the fiction even if the story structurally, the fiction goes to some pretty fantastical or sort of speculative places. And you see that collision, I think, in all of the writing.

Sam McKegney 10:08

Well, I was going to ask that specific question is, you know, do you feel as though with journalism and fiction writing that it’s, you know, the same muscles employed in a different sport? Or, is it different muscles all together? Or, how do you relate them to one another?

Omar El Akkad 10:27

I mean, I, I think of them as antagonistic muscles. So the only exercise I get at all is rock climbing. And rock climbing is great if you want massive forearms. And it’s useless for everything else. Because you’re constantly just doing this right, you’re constantly. And if you’re just doing this, if you don’t go do some push ups, you end up injuring yourself, because there’s such an asymmetry to the muscles, muscle groups. And so I tend to think of it the same way. There’s there’s, you know, nonfiction in general, but but journalism in particular, for me is about answers. If you don’t have answers to who, what, where, when, how, why, you, you don’t have a piece of journalism, just by definition. Fiction is where I go to sit with questions, there’s very little of a sort of prescriptive element to the fiction writing that I do, there’s very little of, if you do X, Y, Z, then things will work out, you know that that element of it isn’t quite there. So, in fact, American War the, the first novel was born of all of the residual experiences that I had from journalism, that didn’t fit neatly into the context of an answer. There were just these open questions in my mind. And eventually, I had to go to fiction to sit with those questions, because I wasn’t able to sort of exercise those particular demons in the form of nonfiction, maybe a better journalist could have, but I wasn’t able to. And so I think of them as sort of, you know, counter balancing muscles, more than anything else. And and, to this day, I think that’s one of the best things I ever did for my fiction writing career was spend those 10 years of The Globe and Mail. And one of the best things I ever did for my journalism career was take Carolyn Smart’s, creative writing class, and having that muscle set helped, helped in a lot of ways.

Sam McKegney 12:22

I heard you say once that the good writing hides behind the bad writing. And could you take me through that? What is the lesson there for aspiring writers?

Omar El Akkad 12:35

I, for me, it’s excavation, there’s a lot of excavation, there’s a lot of sort of peeling back. And, you know, American War was 12 drafts. What Strange Paradise was eight drafts. And What Strange Paradise is about half the length of American War, it’s a much shorter book. And, it’s, I think it was Vonnegut who talked about the idea of how there’s, there’s two types of writers, there’s bashers and there’s swoopers. You know, there’s, there’s the ones who will sit there and think about a sentence and think about a sentence and think about a sentence and then finally write it down and never change it again. And then there’s the bashers will write it down, and then edit it 400 times and go back and, you know, that sort of thing. And, and I like to think that I’m a swooper. I like to think that once I get it down there, it’s right. But I’m the exact opposite, what I need to do is go back and fix it over and over again. And I think, you know, in my very limited experience working with students on their manuscripts and doing that kind of mentorship, you know, all these folks are far more talented than I am. And they have incredible stories to tell. And it’s mostly just a matter of stubbornness, right? You finish the first draft, and especially early on, if this is your first go at it or something. There is a tendency to think, okay, I finished the first draft, I’m 90% of the way there. Now it’s time to clean it up and really get it. And some people when they finally realize, oh, I finished the first draft, I’m 10% of the way there. That’s a crushing thing. And that’s I think a lot of, a lot of people when they drop out of the marathon, that’s the moment that they’re dropping out of a marathon, is when the enormity of what comes after doing the thing, or what you thought the thing was, when that moment hits, is when a lot of people say, you know what, I don’t have another two years of rewriting this thing in me, I’m not, I’m not going to do that. So it’s mostly just a function of, of stubbornness. It’s certainly at least in my case is not a function of talent or skill or anything along those lines. It’s mostly just being able to face the sentence for the 100th time in a row. And that happens at a line level. But it also happens at a more macro level. So in the case of both novels, in the case of American War, and What Strange Paradise I had these moments right around the middle, so in the case of American War, it was like draft six In the case of What Strange Paradise was like draft for, I had this moment where structurally this thing came to me this eureka moment where I thought, yes, finally, I figured out why this isn’t working. And in the case of What Strange Paradise, for example, I had, I decided to write monologues from all the central characters on the migrant ship. And I thought, finally, this is it, this is what’s going to unlock this novel. And I wrote 30,000 words of this stuff, and realized it wasn’t working at all. So 30,000 words that sort of showed up, and then were immediately deleted, because they weren’t working structurally. And when you, when you hit those particular roadblocks, that’s, there’s a real sort of difficulty facing the page after that. But it happened in both, with both novels, and you just sort of have to keep going at it. Because I don’t know that I’ve ever written in the context of a novel a sentence that worked from the start, and go back at it, and go back at it and go back at it and if you can outlast the sense of utility, then then you might have a shot.

Sam McKegney 16:07

That’s somewhat like, depressing to hear in a sense, but it’s enabling at the same time, right? Excuse me, but let’s talk about the novel for a bit. And congratulations on, I mean, it’s, it’s a stunning, stunning piece of work. It’s heart rending, yet hopeful, it’s it’s powerful and its compelled along by these two characters that are unforgettable. And so I’m curious about the genesis of the story. Did it start with those two characters? Or, did it start as the problem of the shipwreck? How did it, how did it sort of emerge for you as a project?

Omar El Akkad 16:44

The closest thing I have to sort of genesis moment, and thank you for that. That was really kind of you. The closest thing I have to a genesis moment is, I was still working as a journalist, I was back in Egypt. It was 2012, and I was covering the aftermath of the Arab Spring. And one night, I was riding around town with an old high school buddy, who was complaining about the rent. Rents too high, rents too high. And at one point, I said, you know, just to get my bearings, I was like, well, what’s the, excuse me, what’s the price of the rent for, you know, an apartment in your building, for example? And he said, well, do you mean the locals price? Or do you mean the Syrian’s price? So, what the hell is the Syrian’s price? What are you talking about? He said, Well, we’ve had this influx of people who’ve shown up here recently. And you can go ahead and charge those people like three times as much. I mean, they have no choice, what are they going to do go somewhere else? And it quickly became apparent that this wasn’t just a rent thing. This was you know, you go down the street to the fruit and vegetable vendor, they hear your accent, they put two and two together and and they know that they can exploit you to a certain degree. And just the the casualness of that kind of cruelty and that stratification of who’s fit to be, to be sort of squeezed dry stuck with me This was all happening in the greater context of all these Arab leaders, talking about “Our Syrian brothers and sisters, or Syrian brothers and sisters” the same way they’ve been talking about “Our Palestinian brothers and sisters” for decades, and it’s all meaningless. It’s just rhetoric. It has no no relationship with what’s happening on the ground. And I was thinking about that and thinking about how I might frame it in the context of a story because again, I was hitting a brick wall in terms of being able to address it in journalism in a way that would satisfy the questions that I had in my head. And so I started sort of sketching out ideas, and it was all very sort of broad and amorphous. And then this happened with American War too, I don’t have a very good explanation of how but there’s always a sort of image that shows up in my head that becomes the anchoring image of not just the two published books, but the, the three thoroughly unpublishable books that came before and all of the sort of stories that I spend a lot of time on, there’s always some kind of image that comes out of the blue that ends up being the sort of anchoring thing for the story. So in the case of American War, it was this image of a young girl sitting on the porch of her home pouring honey into the knots of the wood. I don’t know where that came from, but it did and it became a you know, it became a centering thing and a grounding thing and in the case of What Strange Paradise, out of nowhere, this image came of a young boy running out of a forest and on the other side of the street was a young girl raking frost, which is not something anybody does, you don’t rake frost, it’s not it’s not a thing, but for some reason this image showed up and it was I couldn’t get rid of it. And, slowly these pieces that have no connective tissue between them start to drop into place, you know, thematically I want to talk about the necessary cruelty of survival in the kind of societies we’ve set up, and how easy it is for somebody who’s just getting by, to get by by sort of exploiting somebody else who’s who’s below them on that hierarchy. In terms of images, I have this image of a boy and a girl and I don’t know what to do with it, but it’s giving me my settings giving me my place. It’s giving me the world that I want to walk around in. Another thematic element that showed up a little bit later, was the notion of how much you know, when I was reading these stories about about the migrant crossing across the Mediterranean, how much there was a there was a cruelly fatalistic quality about it, though I’m not talking about the sort of like feel-good Disney fairy tales, I’m talking about sort of the origins of those stories, which are much more grim. And to try and take the context of a fairy tale and reinterpret it in that way. So these things are sort of dropping into place. And then the really hard part is finding the connective tissue between them. How am I going to turn this into a cohesive whole? But that that first night, we were driving around and that story about how you can charge the folks who are who are compelled to come here from Syria, three times as much and get away with it, that was the first spark.

Sam McKegney 21:18

And the scene that you described, that was the the visual image is such a powerful scene, you know, the, the, with Vanna, basically doing busy work, to occupy herself to placate her mother, and then looking across, and almost being unable to allow herself, I think that term is grotesque that is used that if I just keep watching, and don’t help in some way that it would be grotesque. Is there, for me as a reader, that was a striking moment, because it brought me into the mindset of Vanna, and said, this is about complicity. This is about what are our responsibilities to one another. Was, was that kind of message embedded right from the beginning of your thinking on that relationship?

Omar El Akkad 22:06

Yeah, absolutely. I think it was the central, not only the central sort of binding element of the relationship, but also structural part of Vanna’s character, just as an individual, you have this person who is starting to come to terms with the, you know, the lottery of history, and how much is determined her place in the world. The idea that she is afforded a certain kind of life, as a result of the colour of her skin, and her lineage, her ethnic background, where in the world she was born, the class into which she was born, you know, the level of affluence, and so on, so forth. And she’s trying to understand how to be a good person in that context. You know, a lot of the book, a lot of the relationships in the book are about the sort of fundamental asymmetry of kindness, the notion that kindness is a fundamental part of being a decent human being, but it’s more often than not necessitates a kind of asymmetry, a kind of uneven strike, you’re, yeah, sure, you’re reaching a helping hand, but you’re able to do that, because you’re up here, and the person you’re reaching to is down here sort of thing. So she’s in that position of trying to figure out how to be a decent human being in that context. And one of the most interesting things for me about her as a character is that she, she does that thing that’s, that’s very easy to do, when you want to be a decent person in that context from, from a place of privilege, which is put the necessity of being a decent person above all else. You know, what matters is me being a good person, that’s what’s going on, if I have to lie to this kid about what’s happening, and if I have to do whatever, so be it, but what really matters is for me to be good. Which I think is a trait that I’ve certainly, you know, have seen in myself and seen a lot of people, this notion of like, yeah, in this context of ruin, the important thing is that I do the right thing, and I be the right kind of person and I, I sort of thing, so she’s, she’s dealing with all of these things. And she’s 15 and lives on an island. And so, you know, those things are all colliding together.

Sam McKegney 24:12

Some of the tensions that you just were describing in terms of the desire to do right, but it actually being about the self and not actually about help in any sort of in an ultimately sincere fashion. One thing I fascinated about the book is that two of what might be considered the most loathsome characters, or the cruel villain, antagonist characters of the Colonel, and Mohamed, are often the ones who tear the veil away from the fantasies about society. Why give such wisdom to those figures specifically? Because I couldn’t and I feel like I remember Mohamed speaking directly to that tension we were talking about.

Omar El Akkad 25:01

Yeah, so yeah, I think of the novel is sort of, you know, repurposed Peter Pan and those are my two Captain Hooks, right? There’s a Captain Hook of the before chapters, and the captain hook of the after chapters, and one of the things they have in common is that, you know, they might lie to everybody else, but they, they can be pretty honest with themselves. Whereas all of the sort of, morally, quote-unquote, good characters in the book are constantly having to lie to themselves just to get through the day. The, those two characters, Colonel Kethros, and Mohamed, the smuggler’s apprentice on the boat, are in this position where they, they, they’re sort of watching the central element of, of the novel take place, which is a collision of fantasies, the collision of dueling fantasies. One headed in one direction that says, all these people coming over here are barbarians at the gate, and we need to keep them out at any, you know, even if we have to burn the place down to keep them from getting their hands on it, so be it and then the fancy headed in the other direction of, if I can just make it to this part of the world, everything will be okay. And, and the fantasies have such power to them, that reality becomes subservient to to whatever these these two fantasies necessitate. And here you have two people who are, who are forced by, by, by their place in life to, to contend with, with the power of these fantasies, but also the reality underneath them. And it makes them very bitter. I think one of the other things they have in common is they have a very surface level understanding of what it means to be a man. Now, when I was in high school, we used to have this physics teacher who was obsessed with this idea that you should never memorize a formula, you should always be able to derive them from basic principles, you know, so don’t don’t memorize the formula for a projectile in the air. I’m going to give you distance and speed and when you you derive it. And I think someone particularly like Colonel Kethros, I think he’s memorized the formulas for how to be a good strong man, these things that have been passed out and passed down over generations and all the toxicity that’s sort of inherent in them. But he has no idea how to derive these things from basic principles of decency, or, you know, human decency. And so what you have is this incredibly brittle surface layer understanding of what it means to be a man and anytime it’s pierced, and it is fundamentally pierced by the offensiveness to him of having this this refugee child show up. Anytime it’s pierced, all that’s holding it up as violence. You know, so I think that’s one of the other things they have in common is they’ve they’ve been given a rote memorization exercise in terms of how to be a man. And it’s, and anytime they can’t meet the world with that rote memorization, they they immediately descend into violence as a court as a kind of area of retreat.

Sam McKegney 28:07

Can I ask you about Amir’s negotiation of that same question of what it means to be a man because he’s looking to the models of loud uncle and quiet uncle and father, and, and finding dissatisfaction in everywhere he looks in a certain way. But he seems to be gaining more nuance than what you’ve described in those villain characters.

Omar El Akkad 28:33

Yeah, there’s a lot of that dates back to, to or is sort of partially stolen from I suppose my, my own childhood and the sort of the the men I remember being around in my family. You know, when we’d go back to Egypt, and we’d see my extended family or even in Qatar, when we’d meet other, you know, Arab families, and you’d be around these men. And, you know, I happen to have spent the first, used to be half of my life, but now I’m old and middle aged so it’s less than half of my life. But usually, the first half of my life was was in places where, if you said the wrong thing, if you did the wrong thing, if you wrote the wrong thing, if you were seen as believing the wrong thing, there’s a real consequence to that, you know, in terms of, you know, possibly being deported, in the case of Qatar, or over, ending up in a secret prison, you know, ending up in Scorpion Prison in Egypt or something like that. There were real consequences to to what you allowed people to know about you and where you stood. And fundamentally, there were kind of two positions that particularly I remember these older men in my life had taking, which is, one is that you shut the hell up. And you, you know, the walls have ears. You keep quiet to keep your head down, because you don’t want to end up in that place. And the other is to attack it with a kind of brashness to sort of fundamentally take, take the position of resistance and so be. And a lot of these folks who took that position, I’m not talking about, you know, becoming a revolutionary and taking up arms necessarily or something like that. I’m talking about somebody like my father who would, who would say what he thought about the government, you know, which isn’t, you know, it’s not like he was plotting to overthrow the the government or anything like that. But he ended up having to leave the country, ended up having to go somewhere else. And so I think they were they were sort of the, the immediate places that you could go to, the obvious spots to positions to take in the face of a repressive environment is to either keep your head down, and just say nothing. And, and sort of take comfort in the idea that you’re probably not going to get in trouble for it. Or to take the exact opposite position, and then deal with the with the consequences. And I don’t know that either one of those would have worked for Amir as a fundamental way of being in the world. I don’t think he’s that kind of person. So he’s, he’s stuck in the negative space of these two positions. And that’s a rough thing to be in, at any point in your life, let alone in your in your small child.

Sam McKegney 31:10

Could I invite you to read from from the novel for us?

Omar El Akkad 31:13

Yeah, absolutely.

Sam McKegney 31:15

I’ll just mute and pass it over to you if that’s okay.

Omar El Akkad 31:20

Yeah, absolutely. So, for those of you who haven’t who haven’t read it, What Strange Paradise is a repurposed fable. It opens on the scene of a child on the shore of an unnamed western island. He’s the sole survivor of a migrant shipwreck across the Mediterranean. And from that point onwards, the book splits into alternating chapters. The after chapters are what happens after he arrives at the island. And the before chapters are everything leading up t,o to, to that moment. And so it’s got a very sort of, you know, Old Testament, New Testament kind of kind of going back and forth. And what I’m going to read for you is the shortest chapter in the book, it’s a page and a half. And it’s the final before chapter, which is the moment that the Calypso which is this migrant ship, the moment it goes under, in a storm, and I’m not spoiling anything for you, you know that this has happened from the opening pages. But this is the moment that, that the boat goes down. And it’s, it’s the one segment of the book that sticks with me more, more than any other so this is chapter 28.

In the last moment, some held on dearly, leaving splinters of mail and streaks of blood between the boards. And although earlier the boat was filled with screaming, of these remaining few none made a sound. Others, knowing now what was about to happen, what was inevitable, gave in, and without resistance were swept off the deck and into the water. And they, too, made no sound.

In the distance the island, the coloured lights, the music.

One final time the waves lifted the Calypso high. under the force of a tumbling body, mast snapped that its base. The sea overwhelmed, drowning the bloom of limbs that struggled to escape the lower quarters. Turning past the point of rebound, the old fishing boat flung its last few occupants still hanging on to the far starboard side into the air. For an instant, the deck became perpendicular to the surface of the water, and then, like a closing eyelid, met it.

Amir took flight. Headlong into the seaborne sky, the roof of the great inverted world. In meeting him, the water was not cold or concussive but warm and tranquil, it’s temperature the temperature of a body, the temperature of blood. With ease and without pain, he flew past the surface, past the depths, past the places where light and life surrendered and the domain of stillness began. And then lower, farther as the crust of a million interlocking bodies who braved this passage before him and come to rest at the bottom, sick with the secrets of their own allowed morning. Past the smallest flour white bones, past the world at the feet of the world. To the lowest deep, than the lower deep still. Until finally to a dry womb of a place in which were kept safe and unchanging everyone he had ever known, and everyone each of those had ever known, outward forever to encompass the whole of the living and the lived. And each of these the boy met, in their old lives and their new lives waiting, and for each true confession and each he felt into as though there were no barrier between them, no silo of self to keep a soul waiting. What beautiful rebellion, to feel into another, the feel anything at all.

And then he surfaced

Sam McKegney 35:14

Holy smokes, thank you so much for that that is such a powerful powerful scene. And what what blows my mind about it is that the structural conceit of the novel, lets the reader know from the first pages that that’s coming, we know that the ship is going down. And yet when we come to that passage, it’s so visceral and alive and, and new. It’s, it’s surprising it, how it comes to us is with surprise. And I think it’s an amazing accomplishment to have done that. Was there extra pressure on that scene, by virtue of the structure of the text itself? Was that a difficult one to draw together?

Omar El Akkad 36:04

I mean, it was I, for the first few drafts of the book, there was no before and after split. I just found myself, you know, I was doing a straight narrative. And I found myself hitting these moments where in order to keep going, I had to explain a piece of backstory. And so you’d get these flashbacks or you get something like that. And it was a really clunky reading experience. And I didn’t know what to do about it. And then finally, I stumbled onto this idea of a formal split and going back and forth. And the book, to be perfectly honest, the book steals from a whole bunch of different places. It steals primarily from Peter Pan, you know, structurally, the, the idea of Neverland and there’s all there’s all kinds of places where that shows up. Also, from the book of Nicodemus, which was part of the Apocrypha, and has an alternate story of what happens in the time between Jesus’s death and resurrection. Paradise Lost, The Odyssey, all of these places, and, and, um, I, at the point where I, where I did the formal split, I had all of these sheets of plotting diagrams, and structural, you know, ordering things, and it was all sort of it was coming apart of the scenes, it wasn’t quite working. And then as soon as before and after landed, that helped quite a bit. But I knew that the I, once you get into that, you have these two sort of intertwining narratives, but at the end, they have to collide, they have to get to the place where they meet. And so it was their idea of trying to stick that particular landing, that was just this very daunting anxiety inducing thing on the horizon, you know, you knew that you’re working your way towards it. And even on a sort of technical level, you know, initially, the, the book was 17 chapters, because the original Peter Pan had 17 chapters, and that, I to blow that up that wasn’t working, because you then land like this, you know, and you need to land like this. And so you have to find your breaks. Because if you have before, and after, and they’re alternating, you can’t have 15, after chapters and five before chapters, it just doesn’t work. So even just as a technical craft, you know, exercise it was it was difficult, but that was the landing point for for the before the before chapters. And so it was, it was daunting. And and actually, I wrote, I wrote that chapter one night when I was at a literary festival on the East Coast. And one of the things they do there is they give you a cabin. That is that as the main way that they entice you to go there, is they give, every writer gets their own little cabin by the water. And so that’s, that’s why I wrote that chapter. And I wrote it well, before I had reached it chronologically. So I had this thing just sitting out on an island in the distance. And it was a very sort of odd experience to have the island but not the water, or to not know the lay of the water as you’re getting towards that place. But that one, yeah, that one was was was difficult and took a ton of rewriting too.

Sam McKegney 39:21

Well, I will just note that in about five minutes, I’m going to start offering questions from the audience. So I invite our viewers to go to the q&a function if you have a question that you’d like to ask of Omar and and I’ll work my way through a few of those. But I’ll ask perhaps one more question of you before we get there. And it’s it’s about the violence of language. And in particular, the movement between terms like migrant, refugee, illegal and and how those function in in this world and how important they are to the story you’re telling here. So any reflections on that that violence?

Omar El Akkad 40:07

Yeah, I mean, it’s, you know, ever since we moved to Qatar when I was five years old, I’ve been a guest on someone else’s land ever since. And you become you become intimately familiar with the spectrum of terminology starts on one side with illegals, aliens, you know, refugees, migrants, economic migrants. And then on the other end of the spectrum, there’s expats. You know, all the white Westerners in Qatar, there wasn’t a single migrant among them, there wasn’t an economic migrant, there were all expats, which, which was a term that, to me, has always had this connotation of like, they’re doing you a favour by being here, look at them taking their skills to this part of the world, so desperately needs it or something like that. And that entire spectrum of linguistic classification, to me is part and parcel of this thing that I ended up writing about a lot, which is the load bearing beams of of overt violence. You know, overt violence between guns, bombs, the shooting, and the killing, and so on, so forth. But that doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s held up by other much more well dressed versions of violence. The place where I first became cognizant of that idea was when I was working at The Globe and Mail and I went in 2008, I spent about half the year in Guantanamo Bay, covering the military trials. The military, pretrial hearings for Omar Cotter, who was the last Westerner there, and and a couple of other folks. And I remember, we’re walking around in one of the detention camps. And at one point, I asked the officer who was giving us a tour of this place, I say something like so when to the prisoners… And as soon as I get to the word prisoners, one of the soldiers says, we don’t have prisoners here, sir, we have detainees. And it was vital to this man’s entire sense of place and sense of sort of agency, that there be no prisoners here. Because prisoners implies a prison sentence, which has to be defined, a detainee, you can keep forever. There were never any interrogations in Guantanamo Bay. they were called reservations. You know, detainee 2615 has an 8:30 p.m. reservation meant they were going to be taken into the interrogation ship. And then all of the stuff that had come, you know, I came of age during the war on terror years. So you get, there’s no such thing as we accidentally bombed a wedding party, there’s collateral damage, or, you know, there’s enemy combatants. Not that that sort of thing, to me is is fundamental, is a fundamental load bearing beam that allows all the other kinds of violence to happen. So I was I was very much cognizant of how much work language does and allowing this kind of ugliness to take place. Be it in the context of a war, or be it in the context of human beings trying to reach safety?

Sam McKegney 43:07

Thanks so much for that answer. And there’s a number of questions in the q&a, which is great. And I’ll try to just cluster some of them together. But two that work off the hop, are a question about how close did you get to the refugee events that you write about? Did you report for instance, on refugee boats that landed on the Greek Islands? And another question is about the research you did into the perilous journey? Was there significant research into that kind of travel?

Omar El Akkad 43:39

Yeah, there’s, there’s about a year and a half of research, a year of writing the first draft, and a year and a half of rewriting. For both books, actually, it broke down in roughly the same roughly the same ratio. I did do reporting on on the the, the movement of human beings into Egypt, the movement of human beings out of Turkey and into into Europe and into the various landing spots in Europe. I have some personal experience with with people who found their way into for example, Sweden. And of course, living in Qatar, Qatar is 90% non country. It’s 90% of people who’ve come from from another part of the planet. And the majority of those people are from Southeast Asia. And they’ve come and they’ve effectively, you know, Qatar is, you know, this tiny little peninsula. It’s also pound for pound the richest place on earth. And it was built by migrant labour. I mean, overwhelmingly, these skyscrapers were not built by Qataris. They were they were built by Indians, Pakistanis, folks from Southeast Asia who showed up under sort of horrific working conditions. And and you could not live in that place and and not absorb what it meant to be to be in a situation where you’ve left your home. And you’ve been told that you’ll make a lot more money if you show up here, and then you find out that you actually have no rights at all. And you’re stuck here and you work under these horrific conditions. All of that residual sort of experiential stuff, shaped the novel. In terms of the research, it was a mix of personal experience, journalistic experience, and then just pure research, just sitting down with a ton of books. On usually when I’m, when I’m researching an area, I try to, I try to look for books that that were written a little bit after the area that I’m, you know, like, I want some time to pass between the the thing I’m researching and when the book about it was written. And in this case, I wanted the opposite. I wanted the books that were written during, like I wanted, I wanted an immediacy, about about the sort of migrant crossing and the various policies throughout Europe that are intended to basically try to make these people’s lives as miserable as possible. The book that ended up influencing me the most was a book, I stumbled onto it, I don’t remember how but it was a book called The Wandering Jews, which came out about 100 years ago. And it’s a nonfiction account of Jews in Eastern Europe who are escaping horrible persecution, making it to the west and then finding an entirely different brand of horrible persecution waiting for them. And the details in that book, it’s a very fiery book, it’s written by, you know, with a sense of indignation that this is being allowed to happen. The minor details felt like, you know, you could change a couple of locations, and this could have been written in 2015. And that sense of so little having changed, in terms of how the most vulnerable human beings in society are treated, had a huge influence and how I structured the book that was that was the sort of anchoring piece of literature and the research, the research period.

Sam McKegney 47:03

Thank you for that. There’s, there are several questions in the q&a that are intrigued by further reflection on the ending. But I’m going to make an executive on this one and say, I will not have spoilers on my watch. So everyone, go read the book, and then have conversations amongst yourself about the fantastic ending. But I’m going to move on to a different question. This one’s about American War. And the question is, do you find your own experience at The Globe and Mail as a journalist has influenced how journalists and reporters in American War were portrayed?

Omar El Akkad 47:43

Oh, very much. So. Yeah, absolutely. I’m just just talking on the question of the ending, if you if you ever, if you’re if you’re deeply insecure as I am, and you Google the title of your own book, regularly, Google has that autocomplete, you know, did you mean are you know, suggesting? So if you start writing What Strange Paradise, it says, the first suggestion is, What Strange Paradise ending explained. So so there’s, it’s, I’m sorry. Is what I’m trying to say. Anyway, yes, there’s, there’s a lot. There’s a lot of my time at The Globe, that made it into American War. And a lot of it has to do with journalism as an individual pursuit, because obviously, I was I was an individual journalist, but also as an enterprise. So for example, you know, there’s the element of the fixer, which is something I’m not I’m never quite sure when I’m talking to a general audience, whether people instantly recognize what I mean when I say fixer. And for those of you who are not familiar with the term, if 99% of the time, if you’re reading a Western correspondence dispatch, from a warzone, somewhere on the other side of the planet, they were working with a fixer, a fixer is a local, somebody from that part of the world, who arranges interviews, who goes out to the parts of the country that are too dangerous for the Western journalists to go to, who does the heavy lifting. Sometimes their names are mentioned. So sometimes you you will read a story in The Globe or the New York Times, and you know, the byline will be by John Smith. And then at the very bottom of the article, they’ll say, you know, with files from somebody whose name is not John Smith, that person did the work. But they’re, they’re relegated to being a sort of informal appendix to the whole thing. When without them, none of this would happen. And so that works its way into into the story. There’s a scene in American War at the refugee camp, Camp Patience, where there’s a northern journalist who’s down in this camp, and they’re very much relying on fixers, they’re relying on people who know the lay of the land. And certainly this was the case when we were covering events and one of our fixers was a doctor, a former doctor who made far more money working as a as a fixer than he then he did as a medical professional. So things like that, and just the inherent sort of asymmetry of those situations really played into the depiction of journalism. The other the other major part of it, and this, I don’t think ever made it into the final draft. But you know how in American War there are these fake historical documents throughout throughout the novel, there used to be back to back ones that were depictions of the same event. This this massacre outside of the military base, and one was a news article from southern from a southern newspaper, and one was from a northern newspaper, and I made these very slight changes, you know, you throw in the word alleged, or you move a quote around, or something which which happens all the time in journalism. So that all those things sort of needed in and they were all taken from my experience working at the Globe.

Sam McKegney 51:01

There’s a question here about your own self care. It’s how do you personally survive mentally when researching and writing about such morally and ethically difficult topics?

Omar El Akkad 51:16

I I don’t know that I can honestly answer that question in a way that that isn’t also in the form of a question, to be honest. By virtue of the kind of topics that I’m drawn to, and that I write about, I am and have been for the entirety of my 20-year writing career, almost the entirety, a tourist in somebody else’s misery. You know, I want to write about particular topics, and that necessitates parachuting in to the lives and situations of human beings who are among the most vulnerable, and ones who have the most violence done against them, and then heading out because I have the privilege of leaving. And when I was a journalist, I could at least tell myself that the ugly feeling I had doing that was offset by the fact that I was creating something for the permanent record, that I was archiving this and that maybe somebody on Parliament Hill would read the story, and it would cause you know, some kind of reaction, maybe for some good into the world. That’s a much harder calculus to come up with when you’re writing fiction. With fiction, you have to believe that something, amorphus is going to happen to the reader to change their mindset. And I don’t know if that’s true anymore. And so when I talk about, you know, the idea of self care, or the idea of how to deal with writing about these topics, it’s not so much what this does to me. Now, there are difficult scenes to write, there’s a waterboarding scene in American War that was very, very difficult to write. There’s a massacre scene in American War there was right there’s a scene of a man dying on the boat, in What Strange Paradise and what they do with the body, it’s very difficult to write. And obviously, that takes a toll. But I think for me, the more difficult thing is, is trying to figure out if I have any right to do this in the first place, and trying to balance, my need to write about particular things that make me angry, that I find is fundamentally broken in the world. With this fundamental fraudulence, that I feel at creating these made up worlds, to try and tackle these these topics, and I honestly don’t know if I can keep doing it. I don’t know if I can keep creating the conditions necessary to write these kinds of books. And that’s why I said that it’s hard for me to answer this without a question, because usually you’d say but, and then have like a nice wrap up sentence at the end of that kind of thought, but I don’t have that. And I don’t know how to deal with that yet.

Sam McKegney 54:05

Perhaps we have time for one more question. And I note there’s one here. About, Umm Ibrahim, who was one of the characters that stayed with the questioner the most after after reading the novel. And she asks, What was your process for writing that character? And for the foreign mantra, she kept reciting? And why is she so important to the book?

Omar El Akkad 54:34

Thank you for that so so Umm Ibrahim is a composite of… I don’t steal whole people but I steal snippets of people and usually people in my life so she’s, she’s a composite of several of my of my relatives back back in Egypt. For those of you who are not familiar with sort of Arab naming conventions, Umm is Arabic for Mother of and Abu is Arabic for father of, so you sort of informally when you have a child, if you have a child and the child’s name is Ibrahim, Ibrahim’s mother is now Umm Ibrahim. Ibrahim’s father is now Abu Ibrahim. And so so that’s that’s that where that name comes from. And and when we first meet her on the boat, she is reciting, she’s phonetically trying to say this, you know, Help, I am going to have baby. And the date there actually was, it was the, the original due date for my first child. That’s where that date comes from. I was writing this and we are about to have her first child. If you ever go to a place like Egypt, you know, there’s lots of women who wear the niqab. And so you know, the hijab is what you wear around your head. The niqab is the full, the full veil. But some people get that they get that confused with the burqa, which is an entirely separate piece of clothing but but there’s lots of reasons. Everybody has their individual reasons for wearing this kind of clothing. And, and one of the reasons that’s maybe not as discussed in this part of the world where it’s always sort of focused on particular stereotypes. One of the reasons to wear hijab or niqab is just to keep guys from hitting on you. Like, there’s, I know several women who will cover up just to not have headaches when they walk, walk down the street. And Umm Ibrahim is one of those people. She’s wearing this thing and it’s because of all of the stereotypes that are immediately projected onto anybody who’s dressed this way, they they sort of, the offshoot benefit to her is that people leave her alone. She gets a little bit of space from. And she, you know, I mentioned earlier that I had written all of these pages and pages of monologues from each of the individual characters. So hers was that she she was living with a man, her husband, the father of this child, she’s she’s pregnant, she’s, she’s going to give birth and the father of this child is one of those men who… I think these people exist in the West as well, I just I just have memories of this particular kind of man from back home, which is a very pious, very dignified man who has all the outward trappings of a decent person whose day job, you know, necessitates and involves going and torturing people in secret prison. He might work for the government and do horrendous, horrendous things, and then come home and pray and kiss his kids good-night, and that kind of monstrosity. And she’s escaping that. And for her, like a lot of human beings who end up on this journey, the negative space, even if its undefinable is better than the active space, whatever is waiting on the other side is better than this. And so she’s she’s a very machiavellian character in the sense that whatever she needs to do to get to that negative space she’s going to do. But she comes from, from the traits of a number of human beings that I that I grew up around, and, and a number of very, pseudo mechanical means of trying to keep headaches at bay. Keep keep other people keep, you know, get from getting catcalled and all the rest of it. She’s She’s a composite of what a lot of women in my life have done to, to make space for themselves.

Sam McKegney 58:23

Wonderful. Well, I note that we’re at the end of our hour. So I just want to thank you so much for the generosity of your answers for the beauty of your work, and so excited for the novels yet to come. And we can’t wait to welcome you to Queen’s. Hopefully that happens in person. But but who knows. And I guess I’ll invite Daphna back on to say good-night.

Daphna Rabinovitch 58:50

Oh, my gosh. Oh, my gosh, is all I can say. Thank you both so so much. And thank you all, for joining us this evening. I know that we have had a record number of comments in our chat section and a record number of questions. So I trust that you enjoyed hearing from these two remarkable men. This interview will be available on our YouTube channel in the upcoming days. And please join us on February 7, for our second book club to hear 2021 jury member and novelist Joshua Ferris interview, Angelique Lalonde, who is the author of Glorious Frazzled Beings, which was on the shortlist for 2021. If you’ve subscribed to our book club mailing list, you will be sent a registration notice and if not, please visit our website for more details. Again, thank you so much and have a great evening.

Share this article

Follow us

Important Dates

- Submission Deadline 1:

February 14, 2025 - Submission Deadline 2:

April 17, 2025 - Submission Deadline 3:

June 20, 2025 - Submission Deadline 4:

August 15, 2025 - Longlist Announcement:

September 15, 2025 - Shortlist Announcement:

October 6, 2025 - Winner Announcement:

November 17, 2025