2023 Broadcast

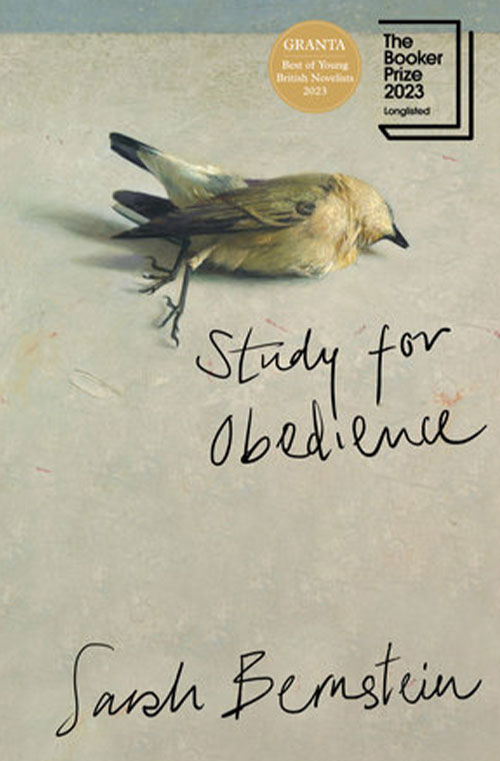

On November 13, 2023, Sarah Bernstein was named the winner of the 2023 Scotiabank Giller Prize for her novel, Study for Obedience, published by Knopf Canada, taking home $100,000 courtesy of Scotiabank.

2023 Shortlist

The 2023 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced the shortlist on Wednesday, October 11, 2023. The five titles were chosen from a longlist of 12 books announced on September 6, 2023.

Jury Citation: Study for Obedience

“The modernist experiment continues to burn incandescently in Sarah Bernstein’s slim novel, Study for Obedience. Bernstein asks the indelible question: what does a culture of subjugation, erasure, and dismissal of women produce? In this book, equal parts poisoned and sympathetic, Bernstein’s unnamed protagonist goes about exacting, in shockingly twisted ways, the price of all that the world has withheld from her. The prose refracts Javier Marias sometimes, at other times Samuel Beckett. It’s an unexpected and fanged book, and its own studied withholdings create a powerful mesmeric effect.”

Jury Citation: Birnam Wood

“Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood is a rare gem, a novel that is a page-turning thriller and a weighty exploration of climate catastrophe and capitalism. Catton weaves a tale of unlikely allies: an idealistic crew of guerrilla gardeners and an inscrutable doomsteading billionaire. This is a satire about political and generational divides that pokes gentle fun at the characters’ foibles, exposing the hypocrisy on all sides. Catton has her finger on the pulse of the zeitgeist and the novel is aptly riven with anxiety. Online surveillance, income inequality, natural disasters, ecological collapse – whatever keeps you up at night, it’s all here. But at its heart, this is a book about friendship and all the ways we try and fail, and try again, to care for each other. With Birnam Wood, Eleanor Catton has penned an instant classic.”

Jury Citation: The Double Life of Benson Yu

Jury Citation: The Islands: Stories

“Heartbreaking, humorous, often disturbing, and always deeply human, Dionne Irving’s ten linked stories in The Islands explore the struggle of diaspora Jamaicans to find belonging and connection in their adopted communities – to find home. The stories succinctly capture the remnants of postcolonial oppression – racist, sexist, or classist – that Jamaicans encounter in their new worlds. In several of her stories the characters – mostly women – encounter moments of unsettling disconnection between themselves and the people closest to them; characters in other stories find connection with the least probable acquaintances. Irving presents her many disparate characters, even the unlikeable ones, in an intimate, lucid style that keeps the Jamaican experience vivid and personal. These stories touch us and stay with us.”

Jury Citation: All the Colour in the World

“With stunning restraint and pathos, CS Richardson has given us a portrait of one man’s journey of the soul — across decades and continents, through loss and grief and hope. Both sweeping and minimalist, All the Colour in the World is Woolfian in its brushstrokes. Quiet moments of being are given as much weight as the chaos of war, and notes on the long history of art balance the depiction of one individual life. As much poetry and mosaic as it is a novel, with not a word out of place, this book is a triumph — a masterclass in how to paint an entire world.”

2023 Longlist

The 2023 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury announced its longlist on Wednesday, September 6, 2023.

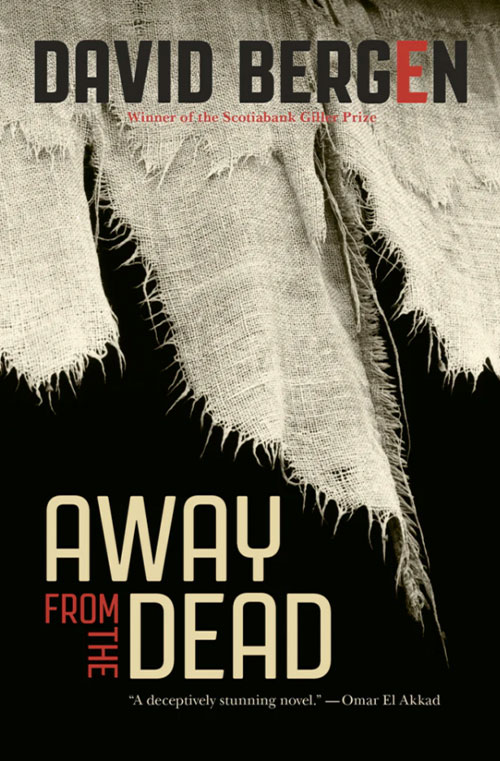

Away From the Dead by David Bergen

David Bergen is the author of 11 novels and two collections of short stories. His work has been nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Impac Dublin Literary Award, and a Pushcart Prize. Among his acclaimed works are The Time in Between, which won the Scotiabank Giller Prize; The Matter with Morris, which was a finalist for the Giller Prize, the winner of the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award and the Margaret Laurence Award for Fiction, and a finalist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award; The Age of Hope, which was a bestseller and a finalist for CBC Canada Reads; and his latest, Here the Dark, a collection of short stories and a novella, which was short-listed for the Giller Prize. In 2018 Bergen was given the Writer’s Trust Matt Cohen Award: In Celebration of a Writing Life. Bergen lives in Winnipeg.

Away From the Dead by David Bergen

For the first three years of marriage, they were happy. Lehn’s desire was purely for Katka, and her desire, though more muted than his, was also directed towards him. Sometimes he wondered if he was too fawning, too unctuous in his affections.

“Do I love you too much?” he asked her.

At first, she laughed and touched his head and said that too much love was impossible. But the question, asked perhaps too often, lodged in her brain, and she began to ask herself the same question. “Does he love me too much?” “Am I simply his vessel?” “Do I have a mind of my own?” “Am I happy?”

He asked her that one morning: “Are you happy?”

“Of course,” she said. And she kissed him on the forehead and left for university. She would be gone all day. Lehn taught most mornings, and worked at his translations, and then, after lunch, he slipped into his boots and walked through the city, usually ending up near the university, always surprised by this, but perhaps not so surprised because he knew what he wanted, which was to catch a glimpse of his wife. He wasn’t jealous. Or was he? He might have been lonely.

That afternoon, upon returning home, he reread Tolstoy’s Family Happiness and immediately saw himself as the husband in the story who marries a younger woman. The newlyweds are happy for a time. Two years. And then the young wife, Marya Alexandrovna, becomes bored and restless. She wants to experience others, she wants to be looked at, she wants excitement. And the husband allows this. But he is angry, and confused, and the more confused he becomes, the more he pushes his wife away.

Lehn was more experienced than Katka and had had various lovers, and because of this he had a knowledge of how desire can be slippery, and happiness elusive. Tolstoy wrote, in the voice of Marya: “Now it seemed quite plain and simple; the proper object of life was happiness, and I promised myself much happiness ahead.”

But it was impossible — happiness — especially if you promised yourself much happiness or expected that happiness could be willed. True happiness came along with sadness, and sometimes happiness spilled out of a regular life.

To try to explain all this to Katka would have been futile. Her behaviour had changed lately. She had taken up with some of the anarchists at the university, who were followers of Bakunin and Kropotkin. She had become a drinker. She smoked thin cigars. Her language was more vulgar. Sometimes, he imagined disgust in her eyes when she was looking at him.

One evening, she asked him to come to a speech that was to be given at the university. The speaker was a man named Maxim.

“A friend?” Lehn asked.

“An intellectual,” she said.

And so he went. And was surprised at Katka’s popularity, the men especially who approached her and looked into her eyes and talked to her, ignoring Lehn, who stood off to the side.

When Maxim climbed onto the small stage, Lehn noted that he was very short. He had no neck and a little head. One eye was higher than the other, as if he had spent his thirty years in life squinting at small print in a very small book. At first shy, he began to speak slowly, quietly, and then he picked up speed, or perhaps not speed so much as power, and his high voice lifted, from his wide mouth towards the higher eye, and then talked about ants, and he said that two ants who are from the same nest will approach each other and if one has its crop full, the other will ask for food and it will never refuse and regurgitates a drop of transparent fluid that is licked up by the hungry ant. Regurgitating food for the hungry is a constant recurrence. And if an ant is selfish, and refuses to feed the hungry, the colony will fall upon the selfish ant with greater vehemence than they would upon their enemies.

When Maxim finished speaking, there were cheers from the gathering, and the cheers sounded like many small animals who had gathered strength and were now howling in unison. Katka was also cheering. Lehn stood quietly beside her. She took his hand and looked at him, all the while opening her mouth, her voice lifting, her eyes angry and full.

They returned home and sat by the stove in their new apartment, the one Uncle Heinrich was paying for. It was late. Lehn said that Maxim’s speech was a complete knock-off. Kropotkin’s words. Verbatim. “He should have told us that. You don’t steal ideas and say that they are your own.”

Katka yawned. She didn’t want to argue with her husband of three years, who had no political views other than the politics of privacy and solitude.

Lehn pulled at his earlobe and asked, “Are you sleeping with Maxim?”

She laughed and said that everything was to share. Even their bodies. “If Maxim needs feeding, I will feed him.”

“So you are the ant with the full crop.”

“I will share.”

“Do you give him your uncle’s money?”

“It is mine to give.”

“I am sad,” he said.

She said, “Poor Lehn,” and she held him.

That night, as she had over the last few weeks, she coughed up blood.

“Is it the chickens?” he asked. “Are you allergic?” She had insisted that they keep a few layers in a cage in one of the extra rooms for fresh eggs, which arrived daily, and when the hen was done laying, she would make good soup. When Katka spoke of chickens and soup, he saw the vestiges of her past, the land and the pigs and the chickens and the grain growing in the vast fields, and he saw that all the money in the world cannot rub the soil from your skin.

Of course, her disease was not from the chickens. It was a sickness that she carried in her lungs. He tried to feed her big meals. She wasn’t interested. Go for a walk in the outside air.

No desire.

He was ashamed to beg, but he was also aware that he didn’t want to have his head beaten in, and so he wrote to Uncle Heinrich. He said: Your niece is very sick. She refuses to seek the help of a doctor. If perhaps you talked to her and told her that she needs the best care, she would find help. She listens to you.

Katka was angry when she learned of the letter.

“You are trying to eliminate me,” she cried. “Trying to pull me away from what I love. And it is not Maxim. I don’t love him. I admire him.”

He listened to her rail, and then listened to her cough and cough, and he carried warm milk to her, and wiped her brow, and fed her soup made from a ham hock.

“Is it poison?” she asked.

Lehn went to a meeting by himself, where he sought out Maxim. He looked down on Maxim’s little head and told him that Katka was very ill. That she needed to get help, but she wouldn’t, because of her devotion to Maxim. “Can you speak to her?”

Maxim said that he admired Katka. She was a woman with fire in her heart. He loved the fire. He loved her strong heart.

“She is dying,” Lehn said.

“I will come,” Maxim said.

When he did not come, and did not come, Lehn grew angry and told Katka that Maxim had promised to come, but he hadn’t, and what kind of man promises something and then disappears.

“You have no idea of what a visionary is, Julius Lehn. He has a burden to bear, and it is the weight of the poor. He is above others intellectually. How hard that is. How little time there is.”

She was sitting in her chair. Her hair was dirty. He said that he would pour her a bath. He boiled water. Mixed the hot and the cold water in the tub, testing it with his wrist, and then helped Katka undress and guided her into the bath. She was too thin. He kneeled by the tub and scooped water up with a bowl and poured the water over her scalp and brow. Some ran down her neck and over her shoulders. Her throat was bare and vulnerable. He thought of the chickens in the cage. He used soap to lather her hair. And when the suds were plentiful, and she was waiting to have her hair rinsed, he said that Uncle Heinrich had sent two train tickets for Badenweiler.

They would leave within a week.

She did not argue.

It was May 1904.

—

Excerpted from AWAY FROM THE DEAD. Copyright © 2023 by David Bergen. Excerpted by permission of Goose Lane Editions. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein

Sarah Bernstein is from Montreal, Canada, and lives in Scotland. Her writing has appeared in Granta among other publications. Her first novel, The Coming Bad Days, was published in 2021. In 2023 she was named as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists.

Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein

It was the year the sow eradicated her piglets. It was a swift and menacing time. One of the local dogs was having a phantom pregnancy. Things were leaving one place and showing up in another. It was springtime when I arrived in the country, an east wind blowing, an uncanny wind as it turned out. Certain things began to arise. The pigs came later though not much, and even if I had only recently arrived, had no livestock-caretaking responsibilities, had only been in to look, safely on one side of the electric fence, I knew they were right to hold me responsible. But all that as I said came later.

Where to begin. I can it is true shed light on my actions only, and even then it is a weak and intermittent one. I was the youngest child, the youngest of many – more than I care to remember – whom I tended from my earliest infancy, before, indeed, I had the power of speech myself and although my motor skills were by then scarcely developed, these, my many siblings, were put in my charge. I attended to their every desire, smoothed away the slightest discomfort with perfect obedience, with the highest degree of devotion, so that over time their desires became mine, so that I came to anticipate wants not yet articulated, perhaps not even yet imagined, providing my siblings with the greatest possible succour, filling them up only so they could demand more, always more, demands to which I acceded with alacrity and discreet haste, ministering the complex curative draughts prescribed to them by various doctors, serving their meals and snacks, their cigarettes and aperitifs, their nightcaps and bedside glasses of milk. Of our parents I will say nothing, not yet, no. I continued to spend the long years since childhood cultivating solitude, pursuing silence to its ever-receding horizon, a pursuit that demanded a particular quality of attention, a self-forgetfulness on my part that would enable me to bring to bear the most painstaking, the most careful consideration to the other, to treat the other as the worthiest object of contemplation. In this process, I would become reduced, diminished, ultimately I would become clarified, even cease to exist. I would be good. I would be all that had ever been asked of me.

Better perhaps to begin again.

There was the house, standing at the end of a long dirt track and in a stand of trees, on a hill above a small, sparsely inhabited town. A creek marked the property boundary to one side, and at night the sound of its fretful flow came through my bedroom window. Looking down the long drive, one could see dense forest, a small town deep in the valley, and beyond, the mountains, higher than any I had seen before. The plot of land and the house which sat upon it belonged to my brother, my eldest brother. Why he ended up in this remote northern country, the country, it transpired, of our family’s ancestors, an obscure though reviled people who had been dogged across borders and put into pits, had doubtless to do, at least in part, with his sense of history, oriented as it was towards progress, turned towards the future, ever in search of efficiencies. From a practical point of view – and pragmatism was naturally of the utmost importance to my brother – he was also engaged in some perfectly reasonable, if slightly perverse, business dealings, for he was, or at least had been, a businessman involved in the successful selling and trading, importing and exporting, of a variety of goods and services, the specifics of which to this day remain a mystery to me.

I came to stay in the house upon his request and initially for a period of six months, leaving the country of our birth for this cold and faraway place where my brother had made his life, had at any rate made his money, of which there was, as I would come to see with my very own eyes, a great deal. I saw no reason to object – I had always wanted to live in the countryside, had often driven through the rural areas surrounding my natal city in the autumn to see the leaves in colour, to experience the fresh air, so different from the turgid air downtown, well known to be the primary cause of the high rates of infant mortality, not that I had children myself, no, no, nevertheless, the air quality and its deleterious effects on public health were of concern to me as much as they might have been to any other ordinary citizen. Moreover, as my brother pointed out, it was not as though I had any specific obligations or ties that could not be broken with ease. I allowed this. Here is how it was. I had so to speak thrown in the towel. My contemporaries had long surpassed me, had, whether by treachery or superior skill, secured their places in life and in their chosen professions. It was said that it was a terrible thing to realise a lifelong dream, and yet still I wondered why they could not let blood a bit. They bloated with success. There was so much time and nothing to be done. I had only a little bit of will. I was not in on the great joke. For a time I pursued a career as a journalist but eventually left the news agency at which I had been employed, not even in disgrace, my time there had run its course, there was nothing at all to mark my going. My efforts over the years to obtain a continuous contract of employment had been in vain, the process had been explained to me as a bureaucratic and not at all a personal one, and yet when I responded in kind, that is to say by invoking the usual bureaucratic processes and fully within my rights making a request according to the general data protection regulation guidelines under the suspicion something fishy was going on, the application was treated as a personal affront and it was made clear to me that I was not helping myself. In truth, I never had helped myself. I left quietly. No one was sorry to see me go. The job I held just prior to my departure to my brother’s home, in the country of our forebears, and which I would continue remotely from the same was as an audio typist for a legal firm, a job at which I excelled, typing quickly and accurately, knowing my work. Nevertheless, I sensed I was unwelcome in the office, which was lined with the usual legal appurtenances, binders and diplomas, leather and wood. I knew that my halting displays of personhood, my miserable insistence on continuing to appear in the office day after day, could only be disheartening to the jurists and paralegals whose voices I typed into a word processor swiftly, precisely, with devotion and even with love, and so they received my leaving announcement with unconcealed joy, throwing a farewell party in my honour, staging a kind of feast and donating lavish gifts. It did not take long for me to set my affairs in order, a matter of weeks, three months at the outside, and, the journey having passed without incident, here I was. The country air would be good for me, I felt, and the seclusion, when my brother did not need me I might take advantage of the various woodland paths maintained by local voluntary groups. I would be quiet.

—

Excerpted from STUDY FOR OBEDIENCE. Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Bernstein. Excerpted by permission of Knopf Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

Eleanor Catton is the author of the international bestseller The Luminaries, winner of the Man Booker Prize and the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. Her debut novel, The Rehearsal, won the Amazon.ca First Novel Award, the Betty Trask Award, and the NZ Society of Authors’ Best First Book Award, was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and the Dylan Thomas Prize, and longlisted for the Orange Prize. As a screenwriter, she adapted The Luminaries for television, and Jane Austen’s Emma for feature film. Born in London, Ontario, and raised in New Zealand, she now lives in Cambridge, England.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

The Korowai Pass had been closed since the end of the summer, when a spate of shallow earthquakes triggered a landslide that buried a stretch of the highway in rubble, killing five, and sending a long-haul transport truck over a precipice where it skimmed a power line, ploughed a channel down the mountainside, and then exploded on a viaduct below. It was weeks before the dead could be safely recovered and the extent of the damage properly assessed; by this time the temperature was dropping, and the days shortening fast. Nothing could be done before the spring. The road was cordoned off on either side of the mountains, and traffic diverted – to the west, around the far shores of Lake Korowai, and to the east, through a patchwork of farmland and across the braided rivers that flowed down over the plains towards the sea.

The town of Thorndike, located just north of the pass in the foothills of the Korowai ranges, was bounded on one side by the lake, and on the other by Korowai National Park. The closure of the pass created an effective cul-de-sac: cut off from the south, the town was now contained in all directions but one. Like much of small-town New Zealand, the local economy depended for the most part on the commerce of truckers and tourists passing through, and when the rescue teams and television crews finally packed up and drove away, many Thorndike residents reluctantly left with them. The cafés and trinket shops along the highway frontage began, one by one, to close; the petrol station reduced its hours; an apologetic sign appeared in the window of the visitor centre; and the former sheep station at the head of the valley, described by its real estate listing as the town’s ‘greatest-ever subdivision prospect’, was quietly withdrawn from sale.

It was this last that caught the attention of Mira Bunting, aged twenty-nine, a horticulturalist by training, and the founder of an activist collective known among its members as Birnam Wood. Mira had never been to Thorndike, and she had neither the intention nor the means to purchase even the smallest patch of land there, but she had earmarked this particular listing when it had first appeared online some five or six months prior. Under an alias, she had written to the realtor, registering her interest in the proposed development, and asking if any of the subdivided plots had sold.

The alias, June Crowther, was one of several that Mira had developed over time and maintained on rotation. Mrs Crowther was imaginary; she was also sixty-eight, retired, and profoundly deaf, for which reason she preferred to be contacted by email rather than by phone. She had a modest nest egg in shares and bonds that she wished to convert to real estate. A holiday home was what she had in mind, somewhere rural, which could be shared among her daughters while she was living and bequeathed to them after she was gone. The house must be new – after a lifetime of repairs and renovations, she was done with all of that – but it need not be purpose-built. A smart prefab would suit her fine, a cookie-cutter sort of place on a cookie-cutter sort of street, as long as the neighbours were not too close, and she was free to choose the colours. All this the farm at Thorndike might have promised; some four months after the landslide on the pass, however, Mrs Crowther received an email from the realtor explaining that owing to the change in circumstances, his client had decided not to sell. It was possible the property would return to the market at a later date; in the meantime, he wondered if Mrs Crowther might be interested in another of his listings nearby – he attached a link – and wished her all the best on her house-hunting journey.

Mira read the email twice, wrote a courteous but non- committal reply, and then logged out of the fake account and called up a map of Thorndike in her browser. The farm, situated in the south-east corner of the valley, was roughly trapezoidal in shape, much narrower at the bottom of the hill than at the top, where it backed on to national park land. One hundred and fifty-three hectares, she remembered from the realtor’s listing, with a perimeter of perhaps eight or ten kilometres. It was not far from the site of the landslide; she switched to satellite view to check, but the image had not yet been updated. The road over the pass still wound smooth and glittering, tacking back and forth as it ascended, interrupted here and there by the grey gleam of sunlight glancing off the roofs of trucks and cars. It occurred to Mira that the image might have been captured mere moments before the quakes: the motorists pictured might now be dead. She told herself this experimentally, as if testing for a pulse; it was a private habit, formed in girlhood, to berate herself with morbid hypotheticals. Today she could not muster pity, so as penance she compelled herself to imagine being crushed and suffocated, holding the thought in her mind’s eye for several seconds before exhaling and turning back to the map.

A windbreak of arrowy poplars threw a toothy shadow over the driveway and up to the house, which was set far back from the road – high enough, she figured, to clear the height of the trees along the lakefront and so command a view across the water. Above the house was a kind of natural terrace, formed by the seam of limestone that divided the more wooded upper paddocks from the open pasture that adjoined the road. Mira enlarged the image and scanned the paddocks one by one. They were all empty. A rutted track showed the owner’s habitual route around the property, and from the angled shadows in the dirt she could see that several gates were standing open. The realtor had not disclosed his client’s name, but when she typed the address into a separate tab, a news article came up at once.

Mr Owen Darvish, of 1606 Korowai Pass Road, Thorndike, South Canterbury, had recently made headline news. He had been named in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List and was shortly to be created Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to conservation.

Intrigued, Mira forgot about the map for the moment, and read on.

Chivalric titles had been abolished in New Zealand in the year 2000, only to be reinstated nine years later by a moneyed politician desirous of a knighthood of his own. It was embarrassing whichever way one felt about it: the monarchists could not celebrate, as the resurrection only proved the Crown could be politically compelled, and the republicans could not protest, because to do so would be to suggest that there was something sacred about a monarchic code of chivalry in the first place, that ought to be beyond a common politician’s reach. Both parties felt disgruntled, and both received the twice-yearly Honours Lists with the same peevish cynicism, concluding, jointly, that all the knighted intellectuals were sell-outs, and all the knighted businessmen were bribes. Owen Darvish, it seemed, was a rare exception. The news of his elevation had come so soon after the landslide on the pass as to give the impression that the knighthood had been offered as a kind of consolation to the Korowai region at large, and that was a kind of chivalry with which neither monarchists nor republicans were prepared to find fault. Darvish had even offered up his house to Search & Rescue to use as their base of operations in the days after the disaster. ‘I take my hat off to those guys,’ was all he said about it. ‘They’re heroes, they really are.’

—

Excerpted from BIRNAM WOOD. Copyright © 2023 by Eleanor Catton. Excerpted by permission of McClelland & Stewart. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

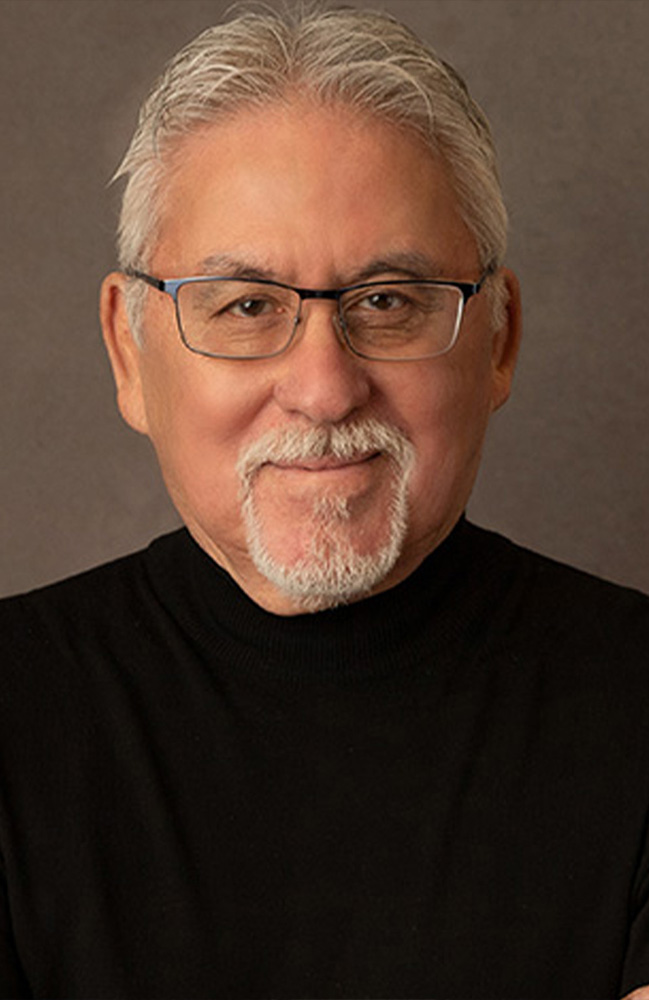

The Double Life of Benson Yu by Kevin Chong

Kevin Chong is the award-winning author of several books of fiction and nonfiction. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Rumpus, and more. He currently lives in Vancouver and is an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia.

The Double Life of Benson Yu by Kevin Chong

A few days after I receive that noxious letter from C., the boy appears for the first time. The picture fills my eyes, and the most expedient way to clear them is by writing it down. I see the boy, on the street, cowering behind his grandmother. That’s his default pose. He’s holding a fold-up cart. His ailing poh-poh nudges him forward. Up until a month ago the old woman pulled the two-wheeled cart herself. Then, one morning, after she’d been coughing through the night, she made the boy do it. On that initial outing, as they embarked on their errand running, she made a point of moving at her typically brisk pace. “It’s just my hand,” she said in Cantonese, with a village accent she used only around family, like a pair of ugly slippers. “It hurts, that’s all. It’ll be fine tomorrow.” But then she asked him to pull the cart again the next day.

Every week, on Sundays, this depleted family unit makes their rounds to the markets for dried scallops, for pea shoots and watercress, for oxtail and tripe. Everyone knows Poh-Poh. She used to teach Chinese school to half of them in the church basement. Everyone stands up straighter, eyes jittering, the second she appears.

Whenever he’s out with Poh-Poh, the boy worries about seeing kids from his class. Their side-eyes and smirks could strip paint. Those jerks will wait until they’re in the schoolyard to tell the boy they recognize his clothes from gift-shop clearance racks and church donation bins. They’ll ask him where his parents are, as though he hasn’t told them already.

Now that he pulls the cart, the shopkeepers direct their attention to him first, as the person who handles the business. They all know better than to see him as in charge, but this way they don’t have to meet the gaze of the woman who would pick their Chinese names from a roll to recite classical poetry.

Today, it’s Mr. Mah, who runs the convenience store across the street. “Dai lo!” he says from the back of the store. He’s finished stacking cans of

soup. “How may we serve you?” he says in Cantonese.

Poh-Poh tuts, her voice like the rasp she uses on her feet before bedtime, and allows the boy—I guess we’re gonna call him Benny—to choose a shrinkwrapped package of snack cakes for acing his math test. One indulgence he’s earned from pulling the cart is getting to stop here first. He no longer has to wait until their errands are done for his weekly treat. “You’re acting as though he’s the one paying for everything,” she reminds Mr. Mah.

“One day he will. Big head, big brain, woh!” says Mr. Mah, rubbing his hands on his flannel shirtsleeves as he follows them to the front of the store. The sides of his face are crinkled from all the smiling he does.

His daughter sits behind the cash register. Benny’s cheeks warm at the sight of the girl. I cringe to picture him this way, fluorescent with hormonal yearning around Mr. Mah’s daughter, Shirley. I’ve changed her name, although the real one is pretty similar. Only a few years ago, Benny and Shirley did everything together—watching TV, playing Transformers, drawing, even eating, on most days, from the same bowl of macaroni, peas, and ham in broth—back when his mother had grown too weak to work and babysat her for extra cash. Now he can’t speak to her.

“Why can’t I have at least one smart child, laa?” the shopkeeper says to her. Shirley’s older brother, Wai, works at the store, when forced, but otherwise runs with the wrong kids, the ones who wear clothes their parents can’t afford. “Look at him,” Mr. Mah tells his daughter. “Always on the honor roll. Nose in books, teem.”

“He takes after his grandmother,” Shirley says in English, staring at her lap as she struggles to wipe her mouth clean of a smirk. She has an oblong face with wide cheekbones and tendrils of hair that escape from her ponytail. Her bright eyes and a readily pursed expression complement a thorny demeanor that the boy will always be drawn to. “Look who I have to take after.”

Mr. Mah wags an open palm at her, his eyes glinting with amusement. “Begging to be hated.”

Poh-Poh slides the cupcakes across the counter and produces a folded five-dollar bill from the lanyard money pouch where she keeps her senior’s bus pass. Shirley opens the register and calculates the change in her head.

“Your girl is even better with numbers than my grandson, gwaa,” Poh-Poh says. “Every child has a different strength.”

The shopkeeper seems stumped by this praise from a woman who offers so little of it. Praise from her always feels unprecedented. As they’re leaving, Mr. Mah gathers his wits and holds out a candy bar.

Benny stares at the treat. Flake. He’s never heard the name before. It’s probably chocolate. It’s probably good. It’s free. But why can’t it just be a normal candy bar? A Snickers or a Mars bar, and not something that came over on a boat?

“A gift for dai lo,” Mr. Mah says to Poh-Poh. “Free of charge.”

“Nonsense,” Poh-Poh says, and hands Benny two quarters to pay for it. Shirley reaches out. He wishes his fingertips weren’t so grimy as they glance along her palm. She turns away when she takes the money.

Benny eats the snack cakes once they step outside, eats them so fast it’s as though he’s trying to hide them from himself. Poh-Poh would chide him for eating so quickly except that she’s in a hurry. He’ll save the candy bar for later.

“That shopkeeper doesn’t pay taxes, woh. That’s why his girl is so good at numbers. Don’t tell her you know all of that, laa,” Poh-Poh says to him once they reach the next block. “Why were you standing around, acting so dopey around Mr. Mah?”

“I wasn’t,” Benny insists, moving a step ahead of her down the hill to their first stop. At night, he will picture Shirley, the way she flutters her eyelashes and tucks in the left corner of her mouth when she’s embarrassed. He sits behind her in their history and English blocks so he can watch her ponytail sway for up to two hours a day.

They pick up vegetables at a greengrocer, chicken feet at the butcher shop. The people at those stores don’t fawn over him as much. At the butcher’s, Poh- Poh slips on the wet linoleum but reaches for the counter to prevent a fall.

Throughout their walk, the big hill back to their cream-colored concrete housing development looms for Benny. The first few days pulling the cart were

muscle-scorching slogs, ones that underscored his softness, and he wondered how Poh-Poh managed that task all these years. But the sum of that effort has made him more resolute, if not stronger. Today, he feels as though he can sail up that hill.

When he turns around to see Poh-Poh midway down the block, her body seems to be twisting, hands aloft like a surfer’s along a concrete wave. She

clamps a handkerchief to a face that’s purple with distress. As Benny starts to hurry back, the cart turns over. Stooping over to pick up the scattered groceries on the sidewalk, he sees Poh-Poh reaching for a lamppost but missing it. Then crashing.

He abandons the cart and races down the hill. When he gets to her, she swats him away. No, she can’t grab hold of his hand. Finally upright, she reveals an abacus of scrapes along her cheekbone.

“Mom!”

Benny sees Steph, still in her waitressing uniform, hurry down from the top of the hill. “It’s nothing,” Poh-Poh says to her. “It looks worse than it feels, gwaa.”

Benny marvels at his aunt’s brisk competency. First she recovers the cart and walks them back to their apartment before jetting off to the pharmacy

for disinfectant and bandages. Then, while Poh-Poh rests, she cooks dinner, humming along to Perry Como on the oldies station while Benny watches her. Steph reminds Benny of Mommy. She has Mommy’s long nose, the kind he wishes he had instead of a flat nose with the hump of a chocolate hedgehog.

She has her double-folded eyelids, a pair more than Benny, who always looks sleepy. She has her ability to tease Poh-Poh, darting her eyes at him with complicity when Poh-Poh grows huffy. In his aunt’s presence, Benny, who’d never dare tease his grandmother, always feels the courage to crack up.

Whenever Steph visits, Chinatown shrinks and the world beyond it emerges. Poh-Poh always complains that Steph isn’t Chinese enough. Because Steph was born here nearly a decade after Mommy—Poh-Poh blames their age gap on the hardships of immigration—she is more westernized. Unlike Mommy, who worked a job preparing taxes, his aunt insisted on attending art school. Gong-Gong was dying when she enrolled, Poh-Poh says, so she didn’t

have the energy to force her to abandon her dreams. Now Steph lives on the other end of town, where she serves breakfasts with funny names. The “Jacked Stack.” “Benny from Heaven” (one of her nicknames for him). “Huevos Rancheros.” And she’s in a punk rock band. The last time Steph visited, she gave him her old Walkman and a cassette of her band’s album. The cover shows the band members leaning against a brick wall in their jeans and leather jackets. They stand with their arms to their sides, blindfolded, with cigarettes at the corners of their mouths. “Do you really smoke?” he asked his aunt, to which she only answered, “In spite of yourself, you are so cute.”

After they finish eating, his grandmother tells him he can either watch TV or play video games. He gets an hour of TV, but only half an hour of gaming— to Benny, a cruelly unfair ratio. She doesn’t wait for him to choose, turning on their thirteen-inch set and, for the first time in his life, cranking up the volume. In his peripheral vision, he sees Poh-Poh lead her daughter into the bathroom. Noticing this, Benny is too distracted for Growing Pains. It’s a rerun anyhow. He stands by the door. Their voices are so low he can barely hear.

“Ah-neui,” he can hear Poh-Poh say.

“I know, Mom,” Steph says in English. “I’ve got it.”

“Do you promise?”

“I promise.” Benny doesn’t have time to ask Steph what she assented to. When she emerges from the bathroom, a quarter hour after Poh-Poh, she stretches out in a yawn. “Bedtime,” she announces. “Nice and early, as usual.” She winks at him. She’s changed out of her work uniform and into clothes from her bag. In makeup, hair done, in a leather skirt. Better places await her. Steph only comes by every couple of weeks, and he feels cheated that she cuts out so early.

I too had an aunt who helped take care of me, but not someone like Steph, who’s modeled after the older sister of a friend—another hopeless crush.

Benny doesn’t know it, but he’ll see his aunt tomorrow when she shows up after the worst day ever at school. That Monday afternoon, the final bell rings and he can’t wait to get home. He pushes through the outer doors but stops when he sees Steph. His chest soars. She’s here for him, and he’s too grateful to wonder why. He hopes she takes him out for hot chocolate and cracks a few jokes. Just the thought of her kindness, given everything that happened that day, steams him open like a mussel.

—

Excerpted from THE DOUBLE LIFE OF BENSON YU. Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Chong. Excerpted by permission of Simon and Schuster Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Clarion by Nina DUnic

Nina Dunic is a two-time winner of the Toronto Star Short Story Contest, has been longlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize four times, won third place in the Humber Literary Review Emerging Writers Fiction Contest, and was nominated for The Journey Prize. Nina lives in Scarborough.

The Clarion by Nina Dunic

She was amused in her vague, big-eyed way. I started to notice things about her. I saw her long face as a carved wooden mask, drawn, detached from the inside, but with eyes showing everything. I started to feel sure of things—I felt she knew everything about me. I had split open, exposed like the jagged interiors of crushed fruit. This is how it felt sometimes, one inch deep on a second joint. I could be known just by someone looking at me; it was a relief, this idea I could be known, without the work. I could be seen, without asking. And another thing—that her knowing was not as witness to my life and its billions of tiny points, but instead because we were the same. And we both saw it. Knowing as a twin, as siblings, as children, the same flesh of one big soul, the same.

“So hi, Peter,” she said.

“So who are you?” I asked.

Apparently she had not expected the question returned to her because her head tilted in genuine consideration. She paused on it, reflecting.

“I’m Zari, but that’s not how they named me when I was born.”

“Hi, Zari,” I said.

The exchange made, she sat back and followed her own thoughts. I looked down and the joint was fading out.

“So we’re the same then?” I asked, and after her eyes returned to me, I motioned for the lighter on the small table before her.

“What?” She handed the lighter over.

I wet my finger in my mouth and dampened the tip of the joint, running along the burned edge, then sparked it. It took the flame, reluctantly. “I mean, we’re the same people then.” I gave her the lighter back.

“How?” Her tone was rising, curious, and her friends were looking at us.

“I mean, we’re the same people. Only we had different parents, different timing, different experiences growing up.”

She winced slightly, and I could see in her tightened mouth that she was trying to determine if this made sense and she was too stoned to understand, or if I was stoned and not making sense. The truth is I had never thought it through very far or talked it out with myself. I had a feeling about it sometimes and normally I would think it out on my own—something real or a tunnel to nowhere?—but now, on this smoking patio behind the club, in the bitter black cold, I had just started talking. But her face told me it was a mistake.

“Well,” she started slowly, again checking herself to see if she had missed it somehow. “Yeah. But parents, experiences, that’s what makes you. That’s who you are. That’s genetics and, you know, childhood, so—” She stopped talking.

“Exactly,” I said.

This quick agreement blanked her because she thought she was disagreeing. I finished the joint. She was staring at me. I was trying to hold on to the part of my mind that could verbalize properly, but I was rapidly approaching the cliff.

“So—” she started, unsure.

“So—we’re the same people. We are the same except for parents, experiences.”

She was suspicious of me now, and I knew it was a mistake, made no sense, I should not have wandered around with my lazy words and tilted mind. I don’t even know why I pushed it again. I should break and run.

“Yeah,” her friend said, the one sitting next to her. “He’s right.”

The two women looked at each other. I know the first woman was bothered that a stranger would offer anything in common, let alone that we were the same—it was too personal, too intrusive, it was not possible. Somehow I sensed that going in; I didn’t know if I was picking an awkward fight, or why. The second woman, I couldn’t read. But she was confident and simple with a wide-open face, long straight hair.

My hands were suddenly seizing, and I realized they were painful with cold.

“We’re the same,” the second woman said, standing up and stretching her back and arms. She showed no notice of the cold. “All of us. Same thing, just variations.” The third woman, who hadn’t spoken yet, also stood, and then the first one as well. They were leaving. “Pretty simple, actually,” the second woman said as they filed around the small table. “Bye, Peter.”

“Bye,” I said, not looking at the first woman’s face. I had walked into it stupidly, stoned, and did not want to see her eyes or mouth twisted in annoyance. Maybe they weren’t, I didn’t know. I waited until they went inside, dropping the end of the joint and grinding it into the ground, then standing up and going inside to be absorbed into the heat and noise of the club—the last ten minutes obliterated by the shock of this second world.

I looked around and didn’t see Billy or Alex; it was late, I could just leave. The crowd was swaying, lights were arcing in a gentle half-spin across the ceiling and walls. I had an ending feeling in me. Everybody looked blurry, happy, and far away. I couldn’t quite place the music or how it sounded, only how my body caved inward as the sound came outward, the exchange of it. I wanted to talk to Billy maybe, I should have asked him first—were people the same? I felt he could go either way. But I felt they were. I felt that believing people were the same was important to me, like a small red stone I wore around my neck.

I remembered a story Billy told about some photography he had done after leaving his career. He had bought an expensive camera, took photos of the streets, thoughtful portraits of strangers, but then he put up a website and had a few requests—would he shoot people’s events for money? Sure, he tried a couple, they went okay. But the last one was some house party; a rich teen had several classes worth of kids over and wanted professional images of their epic night, a crowning jewel for extensive online personas, permanent records of greatness. Billy’s words. So he showed up and walked around and saw a bunch of kids getting drunk, and whenever he entered a room with the camera they all exploded in postures of adulthood, the boys loud and goading, the girls jutting their chins up, everyone thinking the camera was focused on them. Billy got depressed—a middle-aged man with a gut, and having just left the corporate world for somewhat related reasons. He brought the camera up to his eye and pretended to shoot, and after about barely an hour and a half, all the kids were too wasted to notice he had located a large bottle of expensive cognac from the father’s wood-panelled study and just fucked off home. Kids were allowed to be dumb, he reasoned, but he didn’t have to participate. He had taken no photos. Later, when the girl contacted him for her photos, Billy gathered up 250 images he had found online and sent them to her—250 pictures of squirrels. Jumping, hiding nuts, sitting on tree branches, clinging to tree trunks, staring at the camera with their blank black eyes, grey and brown and red ones. Fucking. Squirrels. She flipped out, threatened him, threatened to get her dad to do something legal to him. Billy reasoned the father would be uninterested at best—that type of parent seemed like the kind to produce this type of girl. And he was right. No rich dad ever came crashing into his life with lawsuits or anything else. Billy was done with paid gigs, though.

Would he think people were the same? Those kids, and whoever was sitting in the yellow chair in an empty field? I thought Billy would say no. But I could also see that he would say yes. The hippie in him. He would have noticed the shy kids who winced and turned away when he walked in with the camera. In the other kids, he must have seen vanity as the hard, thin shell that it was—protecting something vulnerable and unformed. And I knew how invigorated he was by strangers, new people, endless sources of new recognition and understanding—there had to be something beyond who your parents were, and the enormous but tiny personal cosmos of things that had happened to you. Maybe none of that mattered—the only things we knew about ourselves, they didn’t even matter.

I didn’t see Billy around. Or anybody else I knew. My body was tired and confused, both up and down, my mind mostly down.

I went for my coat and called a ride, standing near the front of the club, remembering so many rides home in a silent car through empty streets, lulled into another ending with smooth rights and lefts, street lamps and headlights blurred into lines. And then I would be home, familiar and alone, and into bed, alone and familiar. It was an important ritual for me, after this one. The ride home and the bed.

I got my coat back and, as the throbbing music receded behind me, stepped out into the night.

—

Excerpted from THE CLARION. Copyright © 2023 by Nina Dunic. Excerpted by permission of Invisible Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We Meant Well by Erum Shazia Hasan

Erum Shazia Hasan was born in Canada, raised in France, and is of Pakistani and Indian heritage. She designs initiatives to help communities improve their livelihoods, ensuring opportunities for women while protecting biodiversity. A Sustainable Development Consultant for various UN agencies, she lives in Toronto with her husband and their two children.

We Meant Well by Erum Shazia Hasan

There’s a rap on the windshield. It’s a couple of children. They raise their T-shirts, show me their ribs. They want something. Food, money, anything. I look straight ahead, my sunglasses on. We’re not allowed to give money to beggars. And I can’t look them in the eyes while ignoring their pleas. I’d have to be a sociopath to do that. Instead, I continue my conversation with Philippe, the driver, trying to evoke an intimacy between us that doesn’t quite exist.

These are children—like my Chloe—begging, showing their underfed bellies; I should be more appalled by this, but I’m not. If you see enough of anything, it becomes ignorable. Even hungry children.

I once used to hold scrawny children like these. I used to nuzzle their hair under my chin, feel their small palms slide in my underarms for warmth.

The 4×4 laces up the dusty broken road. It’s beautiful here. The sun sears through the window. I hear the staccato yells, the buoyant laughs of the market adjacent to the road. I smell the sea over the sweet scent of rotting garbage. Bougainvillea spills over every broken wall. There are bodies all around us, walking alongside, hips brushing my car door, people crisscrossing in front of our vehicle. Loud conversation, misshapen words from mouths of chipped teeth. It’s familiar—all these strangers holding us in. I’ve stopped feeling most things, but this feels good.

A woman carries twins in her arms and balances a ten-liter plastic container on her head. I wonder which she picked up first. Did someone else place the container on her head? These are miracles of the poor. How they carry so much and don’t break. How they walk in kilometers, while we walk in steps. They have a strength my body can never know. The strength of birthing nine children in a hut or plowing fields by hand. Even their breasts are more potent than mine, producing milk on cue, babies latching as they should. No pumps or lactation consultants here.

Seventy-two hours ago, my phone rang in the middle of the night. It was Burton telling me to fly out as soon as possible. Tickets had been reserved; I needed to confirm. I tried to focus on what he was saying, but was half-asleep, nervous that my daughter would wake up. I tried to sound professional, my mouth dry, annoyed that he hadn’t taken the time difference into account when calling. But then I heard his words and sat upright in bed: Marc is in the worst kind of trouble. The fallout could be dire, for all of us. So, I have to be here, one last time, to clean up his mess. Even though I’d secretly been planning my extrication from this job, from this place, from its people.

On sterile days back home, I miss this country’s noise. I miss how free I am here despite the mosquitos and violence. I even sound different here. An accent takes birth on my tongue. It’s inadvertent; languorous s’s, long o’s emerge. I long for them in a bizarre homesickness that spreads while I’m buttering toast or driving my daughter to Montessori in Los Angeles. A homesickness that doesn’t make sense. Why yearn for war and hardship when you have the Hollywood Hills—the holy gifts of the first world?

Besides, here can never be home. These people, they’re familiar but I don’t really know them. I’m driven among them. I have polite conversations. What am I really doing here? For years, I was convinced I was saving lives.

Philippe and I have a polite relationship. I see him a few times a year when I visit to check up on things. He drives me places; I ask about his family. I crack a few jokes to appear relatable. It’s forced, but he smiles. I can’t help it; the words teem, wanting attachment, even a temporary one. But Philippe will disappear, from my mind and vicinity, as soon as I step out of this Land Cruiser, like all the others.

Despite this, Philippe, in his crisp blue-collared shirt, with his shiny forehead, is the one I trust with my life. If hoodlums show up, tapping their guns on the windshield, he’ll intervene, standing tall between his countrymen and me, the foreigner. Perhaps even giving up his own life.

The locals, they know a first-worlder when they see one. They see me. Sunglasses on, in the tinted vehicle with my charity’s fancy blue logo painted on the door, ignoring emaciated children. They walk by without ever hurting me. That guy sauntering with the rooster, holding it by the neck, he peers through my car window, then walks away. That old man, sitting in the dirt, dusty laminated pictures of 1980s porn stars dangling from the ribs of the umbrella he holds over his head, barely looks up, as though I’m a landmark, a building he’s used to seeing.

If someone ever did attack me, I’d end up in the hospital the UN diplomats use. I’d be hooked to beeping machines charged by generators that will run to the end of time, bypassing power outages that plague the rest of the country. The media would be there in an instant. My smiling face blitzed across TV and phone screens, and magically I’d be repatriated to my land, where I’d appear on talk shows to recount how I survived brutality in a wartorn country.

But nothing like that ever happened, even though other things did. Things that did not warrant a talk show segment.

—

Excerpted from WE MEANT WELL. Copyright © 2023 by Erum Shazia Hasan. Excerpted by permission of ECW Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

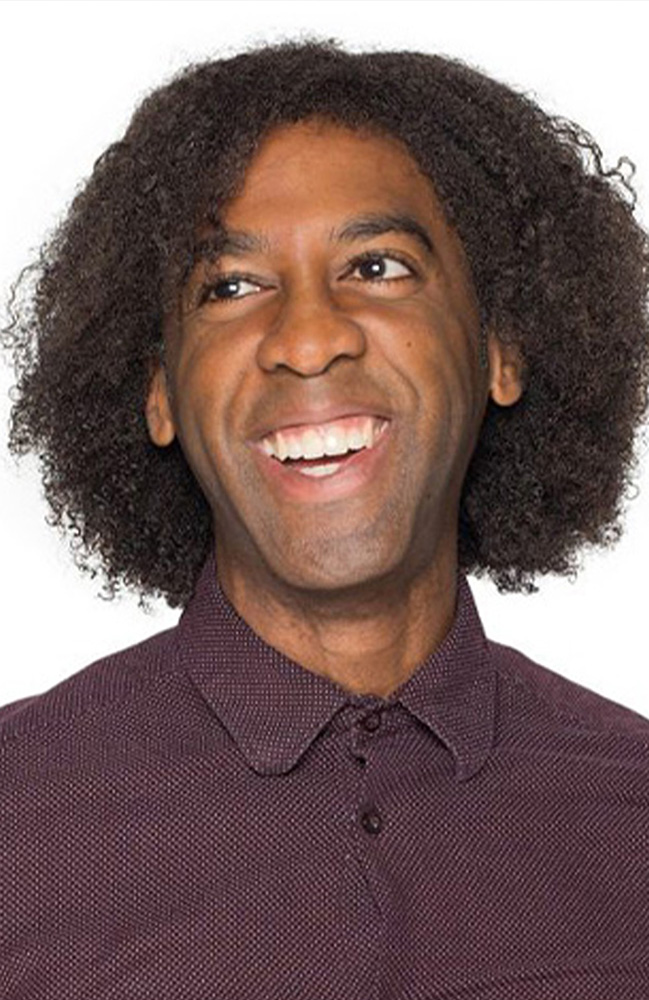

The Islands: Stories by Dionne Irving

Dionne Irving is originally from Toronto, Ontario. Her work has appeared in Story, Boulevard, LitHub, Missouri Review, and New Delta Review, among other journals and magazines. Her first novel Quint came out in the fall of 2021. She currently teaches in the Creative Writing Program and the Initiative on Race and Resilience at the University of Notre Dame, and lives in Indiana with her husband and son.

The Islands by Dionne Irving

You will spend your entire life selling—but this is the first time. So small, you barely reach the counter. You are given a stool. You are told if you work hard, there will be a reward. You are taught to make change. You are taught to make smiles at the customers. You are taught to cut yam, to chop pigs’ feet, to take hot patties from the hotter oven. The burns and scrapes and cuts will last through adulthood, will last beyond death. Injury will always remind you of what it means to work.

On Saturday morning, the shop is clotted with people from the Islands, all there to buy oxtail, and pigs’ feet, to take packages of tripe, leaking, wrapped in heavy butcher paper—and to argue and laugh, and laugh and argue. They lean toward bags of Otaheite apples, or chocho, or tins of Milo. If only you could inhale the coming future in which these foods will become fashionable, in which this education in butchery, in food and flavor, will twenty and more years later help you appear hip and cultured—exotic, even—to lighter-skinned friends in particular. You can’t now know, but you will be the lonely one who understands how blood thickens stew, how marrow complicates flavor, how the perfect pepper in the bin needs to be found.

Forget this work? No. Never. This work defines you, contains you. Allows you. But much later, your friends somehow think you spent your early years traveling—not, in fact, in the back room of a small shop inside a strip mall, listening to the high musical Bajans remind you that Coward dog keep whole bone. Listening to the Trinis insist, Better belly buss than good food waste. And the Jamaicans, the Jamaicans, measuring out mutton with their eyes, asking, Just a toops more fi make mi belly na cry fi hunga. Floors always need sweeping, candies kept clean, not to eat. You dust shelves stocked with things you cannot imagine your white friends at school eating: guava jelly, tamarind paste, cock soup. At the shop there’s always, always a cricket match on the small portable television, and everyone complaining about the gassed bananas and eating gizzada and bun and processed cheese that comes in a tin. How can you explain this, any of it? Your history with food, with work, the way they are fastened together? The way that you love and hate the shop equally?

Your parents don’t understand the shame of Monday morning. Don’t know what it means to have fish scales on your pink Keds, or what it means that your hair smells like brown stew chicken, or that your sandwich is corned beef and salad cream between two thick slices of hard dough bread, or that a boy tells you it looks like mashed brains so you look down and chew and chew and chew. You won’t know for years that it tasted like home and that gift of the British to both plant a flag and impose a culture.

On Saturday you will hear—over and over again— It’s so good to have the whole family here. Working. Over and over again—all day—you will hear it, thinking of other girls your age in ballet classes. Sleeping in. Shopping with their mothers. Settling into Saturday-morning cartoons. And bowls of Cap’n Crunch. You sweep floors, cut dasheen, and try to read when you can, waiting for the book to be snatched from your hands. This shop is your story, your inheritance. Over and over again—as you haul ten-pound bags of basmati, stack tins of coconut milk. I’m glad you are doing it. Just like the Chinese. We need to be more like them. You will remember Oliver Twist (which you read in snatches between tasks) and the workhouse and Fagin. And you can’t imagine why someone won’t come and save you, too. But you remember that these are your real parents, that these Saturdays are your real life. That this world of shop chat, bleaching cream, boxes of dasheen, copies of The Gleaner with newsprint so smeared that you can barely read the stories, and cartons of goat milk and everything beyond it is yours and also not yours. You will always associate work with the coppery smell of animal blood and sawdust and blades that cut fish.

If you could, you’d squint and look into the future. Tell the customers—so much in love with your work, with your working—that the Chinese and everyone but them will own their Island one day. Hurt them. If you could, you would look down, fold your arms, suck your teeth, and tell them that you won’t remember them fondly. You can’t know if they will remember you with fondness either—or perhaps at all. You—the

little girl, swinging with effortless precision, wielding that machete— the magic of it all. You close your eyes and the rest of you becomes the machete, too. Cutting through their dreams, as they lie in bed, their bellies full. Will they remember the sound of the blade cutting meat, cutting bone, before it thuds home on the butcher’s block? Will they remember who did the selling? Or will they only remember buying?

You will just remember the work.

—

Excerpted from THE ISLANDS: STORIES. Copyright © 2022 by Dionne Irving. Excerpted by permission of Catapult. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Wait Softly Brother by Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer

Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer is the bestselling author of the novels All the Broken Things, Perfecting and The Nettle Spinner. She is also the author of the story collection Way Up. Her work has appeared in Granta, The Walrus, Maclean’s, The Lifted Brow, Significant Objects, Storyville and others. Kathryn teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Toronto.

Wait Softly Brother by Katr

Day One

I PULL OFF IN TRENTON and text my therapist because I am sad and I need to hear her voice. Mandy is actually my best friend, but, you know, same difference. There are two Harrier jump jets hovering overhead. The military base is close by and I could have gone straight to Mum and Dad’s, so why do I stop here? The jets are quiet, stealthy, but I can feel anxiety rising, like I’m being watched. I send Mandy that emoji with the skull and crossbones and then the broken heart one. It’s pathetic. I’m pathetic. And when she calls, I answer with the Bluetooth and tell her there’s been a death in the family and I’m heading to my parents for a while.

“Who died?”

“Me,” I say. “I died.”

She laughs nervously. Then goes quiet. Then asks, “Are you okay?”

I say, “You think about leaving your marriage, you fantasize about it, try it on in your mind, but when you actually go ahead and do it, it’s not at all like you thought. You couldn’t really fathom the injury it causes to yourself and then you think maybe no pain, no gain. Then it turns out that it hurts other people, too, and the narcissism that led to you leaving, that self-protective ego thing – or so you told yourself when you did it – is actually serving no one. Or maybe it is serving some unconscious need.”

She really is an analyst. So I know to add that last.

And she bites the bait. “So, you’re on a healing journey.”

Of course, I hate that kind of sentimentality. I picture the font it comes in and it nauseates me. I take a long, slow breath. I stare at the road, at the rain as it starts up again, listening to her voice soften. “Kathryn?” she says. “Are you there?”

“Yes,” I whisper. I’m wondering if it is bad form to yell at her. I don’t because, even though I need to yell, she doesn’t deserve it. It’s me I need to yell at. So I say that “it feels like more of a terrible wound. I keep thinking about the mystic Margery Kempe and all of her weeping and wailing.”

“Tell me what happened. Go slow.” She’s such a good person. I’m so lucky. I say, “It started yesterday. I went out to the back patio to drink my tea. The first day warm enough to do so this spring. And, Mandy, there was a dead cardinal out there. The wind picked up its feathers and ruffled them prettily.” And I’m sobbing.

“Poor thing,” she says, about the bird or about me I am not sure.

“Such a sorry sight to see it robbed of flight. I suppose it hit a window.” Our house is replete with windows, looks out over the lake. It’s worth millions. Enough for all manner of freedoms, you’d think. “I put it in a shoebox and tossed it in the garbage can.”

“And that did it.”

“Yeah, it was the start of a very ugly argument. One of those arguments that dredges up the shit of generations. One there’s no coming back from. It started with me saying I was struggling with my manuscript. That I needed to know more about Wulf, and he said, ‘Your brother is never coming back no matter how much ink you spill,’ and I blew a fucking gasket.”

This morning in the doorway, it’s me and Matthew and the boys – Magnus, Ross and Harry. They are just old enough, teenagers all three of them, to repress why I might be leaving and so abruptly. It’s not them, I tell them. Which only leaves one person to blame. They turn and stare at their father, who shows us his palms as if their bloodlessness is evidence of innocence. He says, “What? I didn’t do anything.” At which I scoff because this is precisely the problem. These arguments go round and round. Twenty years of frustration, fights that give in

to incremental change, that end in lackadaisical, predictable backsliding. Fights that result in him continuing to do nothing, to not be there, to annex himself from us under the guise of work.

“I hope you’ll be happy now,” he says to me the night before I leave.

“It’s not happiness I’m after,” I say.

He says he thought we would be one of those marriages that survived because we lead such separate lives.

It’s like I’m a wayward character in a story I suddenly refuse. For the first two acts, I liked the drama, the rising action, while also waiting for the main players to lock into their respective arcs, to dare to engage, to risk change. But somewhere along the plot it’s clear that it’s me who is changing, me who has outgrown this story, me who finally walks.

“You’ve changed.” His tone is accusatory.

“Yes! Yes, I have.” For that is what I thought characters were supposed to do.

That is how narrative works and how could I not? How could I refuse the call to change? I say, “It’s never been happiness I wanted. Not really. I wanted a marriage.” I wanted the fairy tale is what I mean. Be careful what you want. “Are you sure?” he says. By which he means there will be no going back. By which he means I can’t turn the clocks back on this decision once I make it. Because, whatever happiness or unhappiness might mean to him, he will never reflect, never puzzle, never confront the piece of this story that belongs to him. He’s churlish standing in the doorway to the house like there’s something there he won’t ever let me have back. But the thing I wanted, that’s been a husk for years. He’s a minor character in this. The sort that doesn’t change at all. And the character he won’t change from is one I can no longer abide. You know the part of the Hollywood blockbuster where the hero blasts through fire and escapes? That’s me. Only the fire is a suburban home with a lonely housewife.

O, simpering cliché!

And when I am done telling Mandy all this, and apologizing for trotting out the same old, same old, she says, “I support you.” And for this I am grateful. I watch the aircraft accelerate and disappear. And then she says, “A novel about

Wulf?”

“Well, autofiction.”

“What’s that? Like memoir but not true? Kathryn, Wulf never lived.”

“I know. I know.” That in itself feels sad enough to occupy a story.

I get off the phone and drive on, up the 401, buzzing to the Batawa exit, an entire town built around a shoe factory. Then I head north, up through Frankford, across the Trent-Severn Waterway, and farther north, snaking through Stirling to that godforsaken plot. It’s still raining. The culvert under the laneway is conducting a tumult of water and there are pools and vernal ponds dotting the front field. The old cattle pond has burst at its seams. A couple of ducks airlift as I pull up. I’m driving backwards in time, back to the home where I grew up, where Mum and Dad still live, in a land so rocky even sheep can barely be sustained – a place where the oceans receded after the last ice age, leaving a landscape prone to bog and cedar copse, sweet air, mosquitoes and a history of depression. The land the Scots claimed because it reminded them of the home they’d left, not stopping to consider how their expansion might affect those currently occupying it. The stone croft house where I was raised was built five generations ago. A solid edifice to misery and my family’s devotion to it.

The front door swells shut in the spring and no one ever uses it anyway – too fancy for the likes of us. So, I’m at the old side door, the one through the kitchen. I should have called first.

“What’s going on?” Mum says. Dad’s head pokes out behind her.

“Invite her in, at least,” he says.

“Of course.” Mum shifts aside.

It’s all I can do to sputter out that we’ve argued again, Matthew and I, with the boys all throwing in their two cents, making it worse.

“I couldn’t stand it anymore,” I say.

Her eyes are bright with this information, as if leaving is a possibility she has never considered, as if I have opened up a portal into some grand venture. Then the brightness collapses into an accusatory twinge, her cheeks alive with fear. “So, you just left?” Mum says. A whole lifetime unfolds in an eyeblink. “It can’t be all that bad.”

“Mum,” I say, “it’s been years of not-all-that-bad.”

“And let me guess, you want to stay here.”

I nod, chastened, barely in the door, water now heaving out of the sky and glacier-cold tears, plenty of them, runnelling down my face. I’m calving some horrendous disaster. I can’t decide whether my anguish is about the story I can’t manufacture about Wulf or the one I can’t contain about my marriage. I keep thinking maybe I have picked my marriage apart in pursuing Wulf. It is true that if you start to scratch at the threads of any narrative, you discover it is just another enchantment. You discover there is no such thing as realism. All of it just made up. All of life, all of everything.

I’m sobbing by now, bent over on the couch. No one ever talks about how hard it is to start a story over again.

“Oh, honey,” says Mum, and Dad goes to put the kettle on since words fail him in the primordial way they seem to fail all men.

Mum tucks the Woolrich blanket around me, and Dad hands me a proper cup of tea. They stand there in a kind of tableau, assessing me, waiting for whatever comes next. Dad eventually says, “You poor bairn,” and Mum snickers. The Gaelic always sets her off, since it is not him but rather his own father speaking through him. He cocks his eyebrow at me with some expectation that I will give them reasons, calm their anxiety.

“I don’t really want to talk about it,” I say. And then I dare to say the thing I have been thinking about. I’m trying to make the big deal it is seem like no big deal, to minimize my desire. “I’m writing about Wulf.”

They fold their arms across their chests and nod, mouths arcing to the devil or hell, I do not know which. “There’s nothing to say,” Mum says. Dad just looks stern because, of course, she is right. “Maybe you should call Matthew and apologize. Twenty-five years is a long history to leave.”

“He took a mistress,” I say. Which is strictly speaking true, but it was some years ago and is only a loose thread in the larger yarn. Something I am not above using, though, since it is shorthand for “not my fault, really.” They soften a little but not enough to get me all that far.

“Poor bairn,” says Mum. She is sarcastic of course. There is nothing she has not already seen in her long life. She’s thinking, ‘What’s a mistress, in the long view?’ Mum’s eyes flit to Dad with the scrutiny of one who has stayed and conquered, and something, some energy of that or some secret past, concusses the room.

“You made a promise to Matthew,” says Dad.

Mum nods.

The edifice of marriage – those who’ve committed to it, who protect it to death do they part. To be buried side by side, I think, as the ultimate goal of life, the measure of a successful union. Dad clears his throat and says, “I’d like to call Matthew; I feel sorry for him.” He starts to shuffle toward the stairs, to make a private call.

“Sorry for him?”

He stops and stares me down. “Yes, sorry for him. Who will cook for those boys?”

—

Excerpted from WAIT SOFTLY BROTHER. Copyright © 2023 by Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer. Excerpted by permission of Wolsak & Wynn. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Rooftop Garden by Menaka Raman-Wilms

Menaka Raman-Wilms is a writer and journalist based in Toronto. She’s the host of The Decibel, the daily news podcast from The Globe and Mail. Previously, she was a parliamentary reporter for The Globe and Mail and an associate producer at CBC Radio One. She has a masters in creative writing from the University of Toronto and a masters in journalism from Carleton University. She’s also a classically trained singer. For several years, Menaka reviewed books for the Ottawa Review of Books, and has moderated panel discussions at Ottawa’s Prose in the Park literary festival. In 2019, Menaka’s story “Black Coffee” was shortlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize. She received the youth award at the Alice Munro Festival of the Short Story in 2016, and won Room Magazine’s 2012 fiction contest. Her work has also been published in Broken Pencil Magazine and Acta Victoriana.

The Rooftop Garden by Menaka Raman-Wilms

Matthew hasn’t heard about how cars are heating up the world, so Nabila tells him. She says it’s why the ice at the North Pole is melting, and the more that everyone drives, the hotter everything gets. Soon the ocean will rise and swallow up Vancouver.

She can only tell him things like that when Tara Lynn isn’t listening, because sometimes Matthew gets scared. Then Nabila gets in trouble. So she waits until Tara Lynn is reading baby books with Samir on the other side of the rooftop and then she and Matthew duck behind their hedges. It’s only when they are in their secret forest hideaway that Nabila tells him things like that.

“This is why our forest really is on top of a building,” Nabila says one day. “Water flooded the city and everybody had to leave and then trees just started growing over all the empty buildings. Their roots probably poked through the concrete and started breaking all the glass.”

Matthew is eating his after-school snack, a chocolate chip granola bar. He stops chewing and looks at her. A piece of granola sticks to his lip.

“Where did everyone go?” he asks.

“Maybe some of them didn’t make it. The rest went into the mountains.”

“Why didn’t we go with them?”

Nabila shrugs. “We got left behind.”

Matthew’s eyes get wide. “The forest is eating the city and we’re stuck on a building,” he says quietly, his mouth still full.

Nabila plants seeds so they can grow food. She digs six small holes in a row, drops in pretend seeds, then covers them back up with dirt. She realizes that pieces from the granola bar would make perfect seeds.

“Maybe we tried to go too,” she says as she reaches over and picks up a few bits that Matthew dropped on the ground. “But we got stuck. There was too much water.”

She digs new seed holes and places granola in each one. Matthew squeezes the last bit of the bar out of the wrapper and hands it to her, and she breaks it into little bits and lays them on the earth.

“Don’t waste the chocolate chips.”

He reaches over and picks them out and drops them on his tongue. Tara Lynn always remembers that chocolate is Matthew’s favourite. Every Friday she brings them an after-school treat, and Nabila notices that the treats always have chocolate.

Matthew has only been coming home with them for a few weeks. It started in mid-September; they were walking home one day and Tara Lynn noticed Matthew. He was walking up ahead of them, alone. Nabila wondered why he was allowed to go places on his own, and Tara Lynn said that they should invite him to join them.

So the next day, when Nabila came out of school to meet Tara Lynn and Samir at the edge of the teachers’ parking lot, Matthew stood there, too. Tara Lynn handed them both Tupperwares of apple slices, and they walked home together.

Tara Lynn said she had arranged for him to stay with them after school until his sisters arrived to pick him up. Nabila wanted to say no, but her brother could barely just walk so at least she’d have somebody her own age to play with.

Matthew isn’t in the regular grade three class like Nabila. He is in the two-three split, which everyone says is where they put the smart grade twos and the stupid grade threes. Nabila had never talked to him before. But she knows that some kids make fun of him because one time at recess he had picked up a frog and it had peed on his hand.

Matthew turned out to be okay. When Nabila talks, he mostly just listens. She figured out that if she plans a game, he’ll play it. If she makes up rules, he’ll follow them.

That’s why they always play the forest game. It’s Nabila’s favourite. Her mother is a scientist and teaches Nabila a lot about the environment, including all the ways the world is changing because it’s getting warmer. Humans cut down too many trees, and trees are the things that make the air pure. Then humans drive too many cars, and car pollution turns the air to poison. Glaciers melt and flood the ocean. Turtles swallow plastic bags because they look like jellyfish.

Matthew doesn’t seem to know any of that stuff, so while they play, Nabila tries to explain things to him.

He scares easily. He listens to her with his mouth hanging open, his eyes round and too-pale blue. When she tells him there is a big hole in the sky over the South Pole, he worries everyone will die when outer space rushes in.

They always go to the rooftop after school. Tara Lynn and Samir sit in the gazebo and Nabila takes Matthew to the garden to play. There is a small row of hedges, some rose bushes and a few plants that have big leaves and don’t grow very tall. There are also flowers. Then there are the two sandbar willows that tower over everything else. Nabila loves the trees: they have long, thin branches that stretch up toward the sky, and the leaves hide their forest from everyone else. That’s where she and Matthew play, in the dirt between the plants where nobody else can see them.

After an hour, they all go down to the apartment lobby where Matthew’s sisters wait to pick him up. The sisters both go to high school and one has blonde hair and the other has pink, and they never hug Matthew, just sometimes touch his shoulder.