Scotiabank Giller Prize Spotlight: Kasia Van Schaik

Scotiabank Giller Prize Spotlight: Kasia Van Schaik

September 26, 2023

Kasia Van Schaik’s short story collection We Have Never Lived on Earth has been longlisted for the 2023 Scotiabank Giller Prize.

Kasia Van Schaik is a South African-Canadian writer, teacher, and literary critic living in Montreal/Tiohtià:ke. She holds a PhD in Literature and teaches Creative Writing at McGill University.

We Have Never Lived On Earth, a linked story collection that explores what it means to come of age in the era of environmental collapse, is her first book of fiction. It was shortlisted for the Concordia University First Book Prize and the ReLit prize.

Kasia is the author of the poetry chapbook Sea Burial Laws According to Country. She received the Mona Adilman Prize for poetry related to ecological concerns, the Peterson Memorial Fiction Prize, the Quebec Federation’s Short Story Prize and has been shortlisted and longlisted for the CBC short story and nonfiction prize. Kasia’s writing has appeared in The Best Canadian Poetry Anthology, Electric Literature, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Rumpus, PRISM International and more.

What inspired you to write We Have Never Lived on Earth?

For me, another way of phrasing this question would be: What inspired you to be alive? I wrote We Have Never Lived On Earth because it was my way of interpreting the world—late capitalism, the climate crisis, the moments of testing that can structure a female life—into a shape that I could hold in my mind. And also my hand, now that the book is out! It’s a small story set against a big background, but that’s the only way I know how to write.

Some of the stories in the book are inspired by locations—cities I have traveled through and museums I have lingered in—or conversations I’ve had with strangers. Once while swimming in the harbour in Victoria, BC I met another swimmer on a rock who told me, unprompted, about the most harrowing moment of her life: almost losing her baby in a train station in a foreign city. That story, modified, went into the book.

What do you hope readers take away from We Have Never Lived on Earth?

Alice Munro once said that her work was “autobiographical in feeling” though not always in fact. As I was writing the book, I found that many women of my generation seemed to share a common autobiography of feeling even though the details of our lives differed. I wanted to write something that feels near, uncannily near, to the reader, like a mirror pressed up against the reader’s face, but still feels airy and gracefully incomplete, like memory, or poetry.

My narrator Charlotte has many doppelgangers—girlhood friends, strangers, a drowning victim—and I invite the reader to be one of these doubles, regardless of their background, gender, or biography. I want the reader to feel like they have been dropped into the life of someone close to them, into the distinctive moments of crisis, vulnerability, and decision that shape a life. I hope to elicit recognition, possibly discomfort, but definitely recognition.

Where is your favourite place to write? What is your process?

I love to write in quiet beautiful places, like libraries with elaborate architecture or empty city parks. I write well on trains or beside large bodies of water. But this is just for free-writing and experimentation—the initial acts of writing. When I get down to the business of sifting through notebooks, composing stories, and revising drafts, I work best in my living room at home. I read my work out loud as part of the editing process so it’s better if I’m alone at home. I like to work on still mornings and at midnight when no one else is up.

As much of my book was written in the interstitial moments between teaching and working on my academic dissertation, there has always been for me something illicit and exciting about writing fiction. Recently, I’ve tried to formalize my practice to allow myself more space and time—and permission—to write, but I still want to retain a whiff of that illicit feeling, because I think it invigorates the writing act.

This summer I started working in a studio with other writers and this has been wonderful: we’ve anchored into a collective solitude that also feels supportive and energizing. There is a huge rustling tree outside, a large bare table, no internet, and several different kinds of coffee makers: in other words, heaven.

Is there an activity you do to help inspire writing?

I like to go walking through Montreal’s ruelles vertes, the green pedestrian alleyways in my neighbourhood. The alleys are often filled with murals, little free libraries, kids’ chalk drawings, and cats who’ll brush up against your legs and deign to be petted.

Swimming also helps me think. The goggles, silicone earplugs, and swim cap give me a sense of anonymity and privacy. There is also something about being in another element, thicker than air, that removes you from your life and your work and allows for reflection. Sometimes I’ll edit a whole story in my head while swimming laps in the public pool and then I’ll have to run home to jot down the revisions.

I always write with a book of poetry beside me on the desk, so when I get bogged down in a complacent sentence, I can remind myself what fresh writing looks like. Ezra Pound said that poetry is news that stays new. I don’t see why prose can’t be the same.

What’s a book you recommend others read and why?

I recommend Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water. It changed the way I think about syntax. I once stayed in the asylum in the south of New Zealand where she was institutionalized. It has since been turned into a hotel, but we were the only guests. I also recommend Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy, and anything by Jean Rhys.

I recently picked up Molly Lynch’s debut novel, The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman, and it’s so good! I’ve been savouring it each night in the bath. A few nights ago my foster kitten pushed it into the tub, but I’ve managed to salvage the book on the drying rack. Luckily the ink didn’t run.

Share this article

Follow us

Important Dates

- Submission Deadline 1:

February 14, 2025 - Submission Deadline 2:

April 17, 2025 - Submission Deadline 3:

June 20, 2025 - Submission Deadline 4:

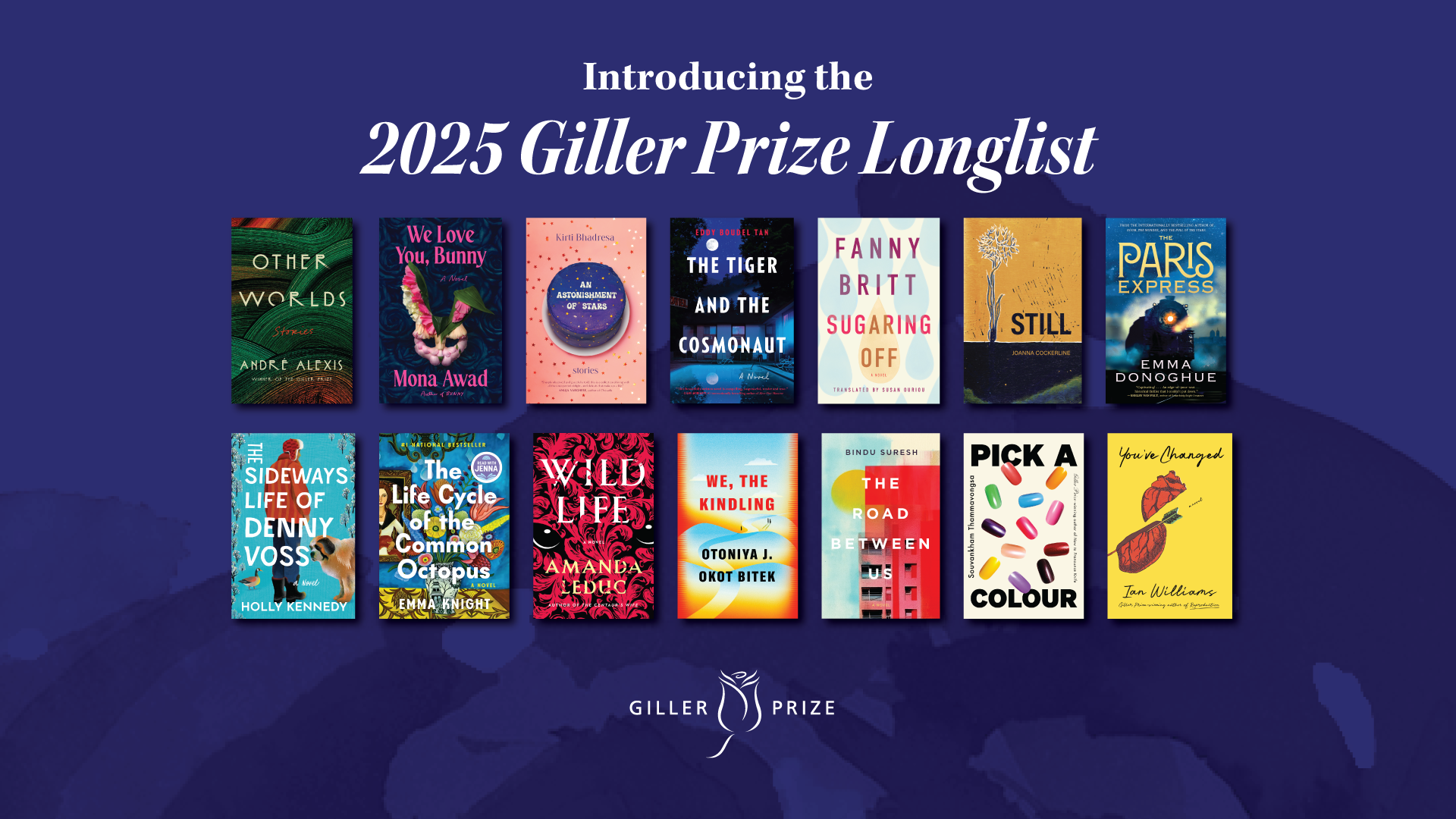

August 15, 2025 - Longlist Announcement:

September 15, 2025 - Shortlist Announcement:

October 6, 2025 - Winner Announcement:

November 17, 2025