Scotiabank Giller Prize Spotlight: André Narbonne

Scotiabank Giller Prize Spotlight: André Narbonne

September 18, 2022

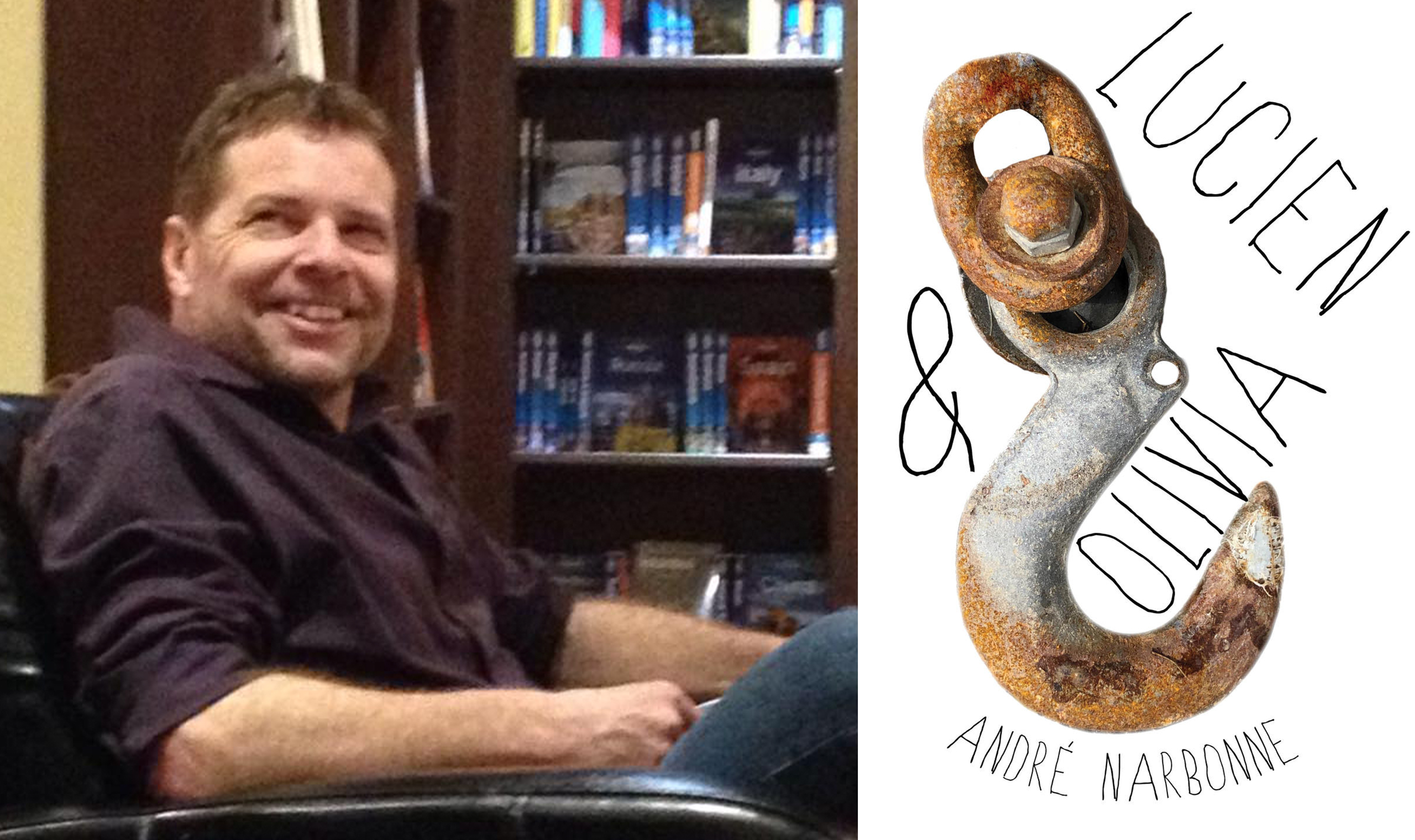

André Narbonne’s novel Lucien & Olivia has been longlisted for the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize.

André Narbonne is the father of four children and the author of three books. He teaches at the University of Windsor where he is the reviews editor of the Windsor Review. His critical and creative writing has seen publication in nearly one hundred North American journals, been anthologized in Best Canadian Stories, and won the Atlantic Writing Competition, the FreeFall Prose Contest, and the David Adams Richards Prize. A short story collection, Twelve Miles to Midnight, was a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Literary Award. A poetry collection, You Were Here, was published by Flat Singles Press in 2016, and his first novel, Lucien & Olivia, was published with Black Moss Press in 2022.

What/who inspires you to write?

My inspiration to write comes from other writers. It comes from a sense that writing is a way of entering into a conversation that’s been going on for a very, very long time.

My influences are many. A lot of names I can’t remember. I read their work in Fiddlehead or another journal. This one I know: in high school I read Wayman in Love and thought, “You can do that?” I remember the jolt. Much better than the poetry I listened to on the top 40. Many of my writers are not my contemporaries—they come from classical Greece, Victorian England, Canada before the Centennial. When I’m jogging or biking the stuff that comes to mind tends to be poetry.

Do you have a favourite passage/quote from a book?

I have Alan Sillitoe’s opening to The Lost Flying Boat tacked to the bulletin board in my office at the University of Windsor.

“A listener from birth should not be surprised if his first occupation turns out to be that of wireless operator. So with me. I listened through earphones to messages which came invisibly from the sky, and was able to write, though not always understand, any language which used Morse symbols … I listened with the greatest intensity of which two ears are capable. Such willingness opened a way to the inner voice, and twenty-five years later all details of what happened to the flying boat Aldebaran and its crew of eight became clear, so it is perhaps as well that I waited before writing my account. By paying attention to the faithful voice I leave out nothing which insists on being told.”

I find it soothing in its way.

Is there an activity you do to help inspire your writing?

I’m a plotter. I spend a long time thinking about what I’m writing before I commit anything to paper or computer. The imagining part usually takes place along the riverfront in Windsor when I’m jogging or biking, which I do pretty much daily. I believe Joyce Carol Oates has a similar process. I’ll sketch out an idea and jog it out. It’s not paint-by-numbers. At the computer, I give myself room for play. What I type necessarily trumps what I’ve thought about earlier, but the scenarios I’m typing into shape have already been visited.

Because I have three children at home, I write early in the morning. I set an alarm. First coffee is for writing.

Do you have a tradition for every time you finish a book?

When finished a book I don’t think I have a tradition in the sense of writing it on the calendar. There’s always a sense of loss.

What are you reading now?

At present, I have three books open that happen to be Canadian: The Imperialist by Sara Jeannette Duncan, The Blue Castle by Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Razor’s Edge by Karl Jirgens.

What is your favorite CanLit book?

When I was thirteen I took a very long bus ride from Wawa to Toronto. Before getting on the bus, I picked out a book from the store where the bus stopped: Three Cheers for Me by Donald Jack. That’s the CanLit book that gave me the most pleasure at the time that I read it. I laughed my way to Toronto. I think the first trilogy—Three Cheers for Me, That’s Me in the Middle, It’s Me Again—tells the greatest love story in CanLit. Probably the most controversial thing I’ll write here is that I’d pick Katherine and Bartholomew over Anne and Gilbert as Canada’s greatest sweethearts.

My favourite book as an adult is Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry. An argument could be made that that is CanLit.

What would your job be if you weren’t an author?

Someone once ran into me after several years on Spring Garden Road and asked if I was still writing, and I wondered how it was possible. How could anyone who writes ever stop being a writer? I don’t have a concept of what I’d be if I wasn’t a writer.

What is your favourite book from childhood?

From childhood, Le Petit Prince. My father died of Alzheimer’s this year. It was the first book he gave me and the last book I read to him.

Is there a book that you find yourself reading over and over again?

Too many books to name. I’m a voracious repeat reader. Two of the books I’m reading now I’m repeat-reading.

How did you know you wanted to be an author?

Recently, in a box of things from high school, I came across a copy of Writers Digest. The issue was addressed to me in a mining town in Northern Ontario, where I lived in a trailer. I was sixteen and had picked my profession.

What inspired you to write your Scotiabank Giller Prize-nominated book?

The impetus was the political landscape of 2015. I wanted to respond to the transactional worldview that was becoming normalized in the American election. I wanted to write a book in which the value people found in themselves was proportional to the value they found in others. James Baldwin says this in Nobody Knows My Name: “A man can only see in others what he can see in himself.” That was the argument. Not necessarily an indictment, although it could be.

I also wanted to write a sailing story for our/my time. I wanted to get it right. I spent ten years at sea as a cadet then a marine engineer. The eighties, when I sailed, was the last time the life was truly isolating. I don’t know what the culture of sailing is like now in an age of cell phones and computers. In the eighties, when at sea, you were at sea. For better or worse. It was like having one foot in a modern world and the other in the 19th Century. I wanted to write into the conversation I was having with Melville, Conrad, Monserrat, Mowat, thinking I could contribute something new.

And, I wanted to write a novel that would move people. To argue for the value of other people would require creating value in my characters. So I wrote a love story.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

I hope Lucien & Olivia stuns them, shakes the rigidity that comes to all of us, the defensive postures that make us unbendable. Olivia says this to Lucien:

“Do you know about comas? If you go into a coma for a week or even a few hours, your joints calcify. It can take months to rehabilitate and fully use your limbs again after even a brief coma. So it is with people. They go into spiritual comas and the pain of rehabilitation, if they have the imagination to attempt it, is too great. They stay emotionally calcified….Sleepers dream they’re awake.”

That’s the politics of the book.

Share this article

Follow us

Important Dates

- Submission Deadline 1:

February 14, 2025 - Submission Deadline 2:

April 17, 2025 - Submission Deadline 3:

June 20, 2025 - Submission Deadline 4:

August 15, 2025 - Longlist Announcement:

September 15, 2025 - Shortlist Announcement:

October 6, 2025 - Winner Announcement:

November 17, 2025