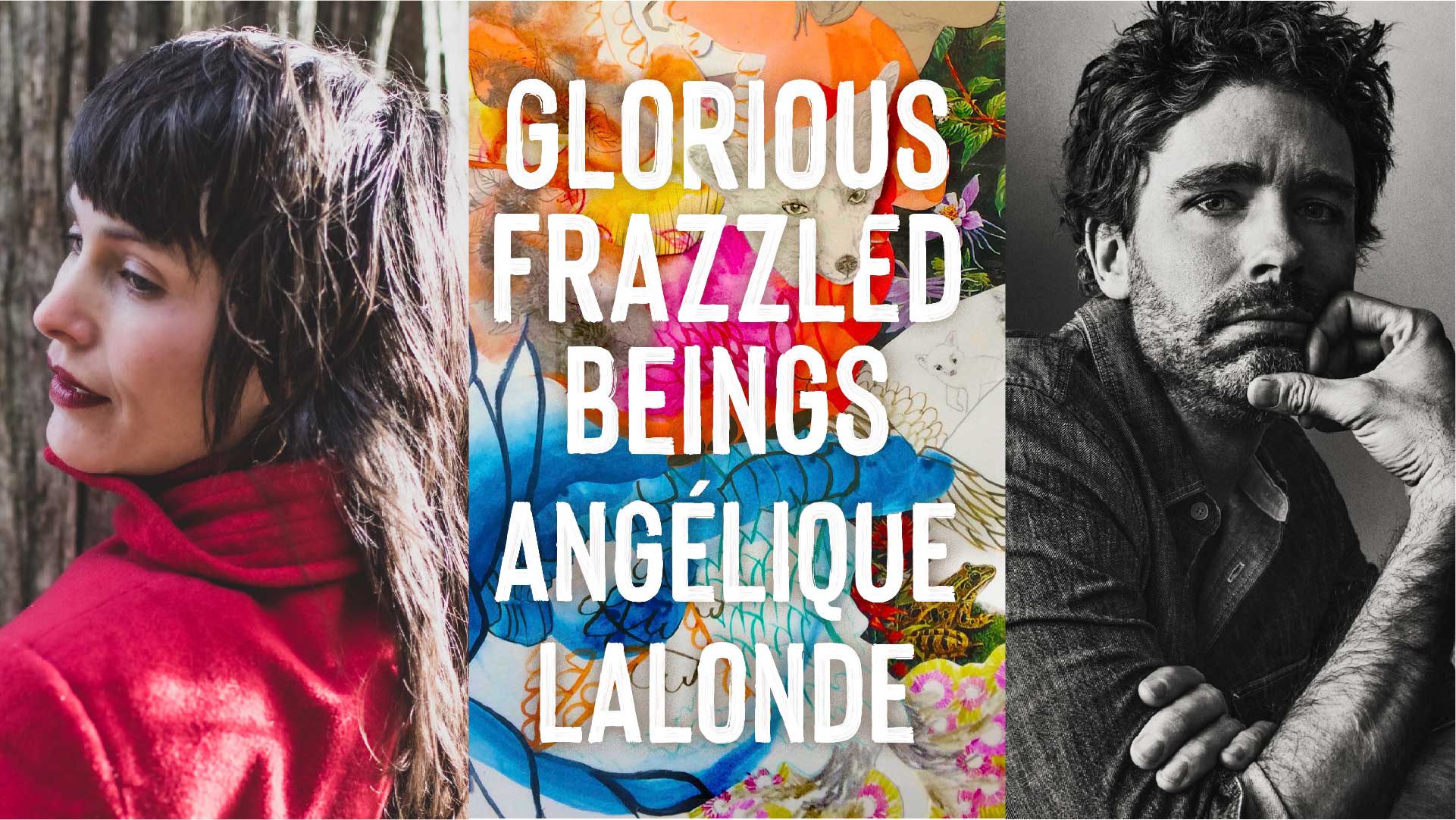

[Video] The Giller Book Club: Glorious Frazzled Beings

[Video] The Giller Book Club: Glorious Frazzled Beings

February 9, 2022

Daphna Rabinovitch 0:00

Good evening everyone. My name is Daphna Rabinovich, and I’m thrilled to welcome you to the second Giller Book Club of 2022. This year we will host 11 book clubs from now until the end of June. Please check our website for the complete list because you do not want to miss a single one. And please make sure tonight to have your Zoom on a side-by-side view for the best possible experience. It is my profound pleasure tonight to introduce you to our interviewer Joshua Ferris. Joshua was a member of our jury last year and as the author of three novels, Then We Came to the End, The Unnamed and To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, as well as the short story collection, The Dinner Party. His latest novel, A Calling for Charlie Barnes, was published in September 2021. He was a finalist for the National Book Award, winner of the Barnes and Noble Discover Award and the PEN/Hemingway Award. To Rise Again at a Decent Hour won the Dylan Thomas Prize and was shortlisted for The Booker Prize. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker Magazine, Branta and Best American Short Stories. And right now he lives in New York. Tonight, Josh will be interviewing Angélique Lalonde, a finalist for the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize for her wondrous short story collection, Glorious Frazzled Beings. There will be lots of fascinating questions and a reading. And if you’d like to join in the conversation, please submit a question using the q&a button at the bottom of your screen. So please join me in a hearty welcome for Josh and Angélique.

Joshua Ferris 1:55

Hello. Hi, Angélique.

Angélique Lalonde 2:02

Hi, Josh.

Joshua Ferris 2:02

There we are. How are you?

Angélique Lalonde 2:04

Here I am. I’m good. How are you doing?

Joshua Ferris 2:07

There is, I’m pretty good. There is a rumour that you’re having weather events where you are. Is that true?

Angélique Lalonde 2:15

Yeah. A little bit. A little bit. Yeah. So we have some bad weather.

Joshua Ferris 2:20

Though power went out or something? And that’s a fear for us.

Angélique Lalonde 2:24

Yeah, just a little bit. I think hopefully, it will be okay. But there was some fluctuations. So I might disappear on you.

Joshua Ferris 2:30

Okay, well, if if you do, I think I can handle it. Here’s what I’ll do. And I’ll let everybody know this, I will just sing your praises some more. I will maybe just sort of bore down into one particular story that I really loved. Maybe if you don’t go anywhere, we can talk about it directly.

Angélique Lalonde 2:49

Sounds good.

Joshua Ferris 2:50

All right. You know, I have to say that I got so excited to interview, to interview you to finally meet you and talk about this book that I so love that it blew right past me that I should come up with an introduction for you. I was like, well, nobody needs an introduction to Angélique Lalonde. Once, once they read these great books, you know that? The really fabulous thing actually, maybe this is why you so thoroughly disappear in these stories. I mean, I imagine there’s some autobiographical elements somewhere here or there. But there’s just so, there’s so much of the rest of the world is channeled through them that I thought, well, maybe this doesn’t even matter. A biography doesn’t even matter.

Angélique Lalonde 3:36

Maybe so.

Joshua Ferris 3:37

But I do have a biography here. It’s the, it’s the one that you printed. So I’m assuming you’ve approved of it. And I’m going to read it and then we’ll we’ll get down to chatting. Angélique Lalonde was the recipient of the 2019 Writers’ Trust McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize, has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and was awarded in an emerging writers intensive at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Her work has been published in numerous journals and magazines. Lalonde is the second eldest of four daughters. She dwells on Gitxsan Territory in Northern British Columbia with her partner, two small children, and many nonhuman beings. She holds a Ph.D in anthropology from the University of Victoria. And here is the book that, oops, oh yeah, it goes funky when you put up. Glorious Frazzled Beings that I just, I just loved. I mean, if you ask anyone on the Giller Prize, any of the other jurors on the subject of Ferris on Lalonde, they’ll just roll their eyes because they got, they had, they got sick of me afterwards. I was I was bowled over you don’t have to tell you how it how it comes about. Maybe you know this, but and maybe the folks who are dialing in know it too, but I’ll explain it anyway. The Giller, you get um, a set of books that are unique to you, and those books that you like you pass on to the other jurors. And I was, I was gifted with yours and, and at first it comes in a funny shape and and I thought, well, I don’t know I don’t like this book because that’s how you have to deal with the Giller. You have to be immediate to be really, really shrewd. And so I started reading it. And I thought this first story is, I’m confounded and amused in equal measure. And you know, to be confounded is a great thing during a Prizze because you get a lot of books that don’t confound you they, they quickly get assimilated. And you’re like, I know what’s going on here. But this was so mysterious and, and then the second story was even more miraculous. And then Malarkey, which is the third story, which I think you’re going to read from tonight. I was, I’d said, you’ve got to, I said to my wife, “You’ve got to stop what you’re doing. And read this story. It’s, it’s genius. It’s genius.” And I just admire them all like that. And I want to say congratulations to you for having written and thank you for writing it on my behalf.

Angélique Lalonde 6:08

Thanks. That’s lovely. And, yeah, it’s amazing to, for it to end up on the longlist and then the shortlist. And then just to hear about the, yeah, some of the things, the process behind that is, it’s lovely to, to learn about, and to know that my book could have had some kind of effect like that.

Joshua Ferris 6:32

Yeah, well, I did. And so let’s just, let’s just talk about it. Um, you know, maybe it would be helpful just for me to, for the folks listening and for you too, to just hear what my experience was like with them, because they’re, they’re really special, and they’re unique, and they’re and they’re, I don’t encounter. I really had a hard time arriving at what aesthetic framework, I should understand the stories through they seemed, they seemed really very original to me. And, you know, some of them are more traditional than others. And some of them are really, they work in a mysterious way that I, I really had to reach back like I think of a little bit I think of like Robert Walser and, but I really mostly thought about Kafka the extent to which Kafka’s mysterious, and, and not all, not really writing for an audience. In any event, at first, there’s this dimming awareness about like a private language being spoken in your stories, a language of mystery, and you know, private intentions that tap into secret realms or unknown realms. And at first, it kind of makes the fiction look either mystical or experimental. But quickly, then there comes into view evidence of this feracious mind synthesizing a lot of contemporary information into narratives like issues of gender, politics, family, the environment, and that’s just to name really just a few. And then that comes accompanied by this great specificity. I mean, I fell in love with the first story because it’s a abstract story about the Lady With the Big Head. But you have a kid out there filming him with the smartphone, and the one of his mother’s calls him a dickhead, like there’s a specific specificity to it, that sort of… Not only are these every day, of every, details of everyday life, but also the most subtle registers of psychology. And so those that like experimental label kind of can’t quite make its purchase. And then later I came to feel, I recognize, like this enormous spiritual element working throughout, that seems to suggest access to the spectral world or higher planes or just liminal, a liminal existence, and what is really what’s in the end, I suppose called, called wisdom, you know, so I really thought that the way that those things work, you know, it doesn’t always, those three elements, you know, the private language, the specificity and the mystical stuff that doesn’t appear, they don’t appear all the time in every story, but your best stories, bring them all together and work in this way that just really moved me. So I guess I’m just gonna really start with the most basic question that I could ask you, which is do you have an audience in mind when you write?

Angélique Lalonde 9:33

Yeah. So I thought about this one a little bit, because I’ve been asked it a couple of times, and I didn’t really know how to answer at first. And at first I thought, well, no, I mean, I’m just writing these stories for myself because I did write these stories just living up here in the Kispiox Valley in Northern British Columbia, where there’s not a lot of people around and, and I did it mostly at a really quiet time after I finished my Ph.D. I decided I needed to take a break from everything and I moved up here to just be like in a closer relationship with the land. And so that was really an opening time, like, I’d been in academia for so long. I just wanted to be in my body, and I wanted to be on the land, and I wanted to feel the world. And the stories started coming once I did that. And I, and then I just wrote them for myself. And, and then at some point, I thought I had, I had my first child and, and then I started to get a bit lonely. And I was like, oh, like I’m not having conversations with, I’m having really, really interesting conversations out there with myself and with the world that I’m interacting with. But I feel like maybe I need a little, a little bit more. Like my baby’s wonderful, but like, I don’t know, I just yeah, I wanted to reach out. So I did. And then I published Pooka, which was the first story that I published, and then ended up winning the Journey Prize, which was really encouraging and, and then I had all these other stories that just got written over the time that I was here, and then I decided to make a book out of them. So, so I had me in mind and the world and my relationship and all the things I was processing. But I read a an interview recently with Kurt Vonnegut, and he said in his interview that he realized at some point, he was writing for his sister. And then I thought, well, of course, I, my sisters, out of anyone in the world would read these stories and get pretty much everything. So I think in some way, especially a lot of the humour, they’re there with me as well, that sort of private world that we shared as children that, that I think has all these elements, the magical, the mystical, the language, the play between language, because my first language is French, my parents speak French, to us and at home, But I’m basically illiterate in French. I can’t really read or write in French, even though I still speak French to my parents. So language, and we grew up in an English speaking place. So from a really early age, there was a private language at home, and a public language all around us. And I had to learn the rules of the of the public language while having this private language at home. That, and my mom also is a very mystical person and has a really profound and deep relationship with the natural world and, and with place and with animate beings. And, and so that was, magic was always part of our life in every sort of aspects of being around her. So I think, I think that’s kind of the long answer to the question is that I think there’s they’re, they’re there. And they’re, there’s that that yeah, that that feeling of like the space and childhood that’s, that’s so fluid and has so many possibilities in it that we haven’t constrained yet.

Joshua Ferris 13:01

Yeah. That private, private languages. That’s cool about your parents. I mean, I had no idea, right. But that makes perfect sense. You, as a kid internalized two worlds, basically, through language, which is something that you’re, a move you frequently make. A move I love where you’re, you’re you have a heroine or protagonist of some sort, who, who needs that secret world. And she is usually, she needs to make some adjustment to protect her secrets and her, her created world from the profane one that’s invading, either through the form of partners or children or strangers or whatever the case may be. Yeah, you know, I mean, I think I think that that’s where some of the best writing comes from. I mean, Kafko is writing for his friends. Vladimir Volkoff was writing for his wife, Kurt Vonnegut was writing for his sister. You know, when you, yeah, one of the dangerous things is to think that you’re writing for the whole world. You know, you can just imagine how terrible that writing usually ends up being. Yeah. These stories, in my opinion, are fairly unconventional. Do they seem unconventional to you, or simply naturalistic accounts of like, the way that the world is?

Angélique Lalonde 14:26

Yeah, I think I think there’s both of those things happening. I think convention is a really interesting thing for me. I think, partially there was like, we grew up culturally different than the people around us. So I got interested in convention pretty early and trying to learn what the rules were. And so I spent a lot of time doing that. And then at some point, in my later like, early adult life, I kind of realized how boring it was. And once I kind of figured out the rules, I wasn’t all that interested in following that, that much anymore. I mean, I live a fairly unconventional life up here and that, you know, I mean, compared to the busy kind of modern world, there’s a lot of like time and energy spent on like growing our own food, and being in relationship with the land and what the land is doing. And then when I’m writing, I get this like, real, like, it is natural, like, I don’t know what I’m going to write ahead of time I get here and like, something sparks and I start writing it. But then as soon as I start writing it, then I have to start making decisions as I’m doing it. And I’m, and I’m asking myself questions, what’s it doing? Where’s it going? And sometimes it goes like down to like, somewhat conventional path. And then I think, Oh, well, what’s going to happen next, here’s what I think should happen, I’m going to do something else. And then, and then maybe other possibilities, sort of like arise multiple ones. And then I have to make a decision about where it’s going to go. And, and I mean, I want to surprise myself when I’m writing otherwise, it would be boring. So I like that aspect of it too. And and, and so I think that like sometimes where the humour parts of it comes in as well. Like, I want to bring things in that surprised me and or things show up that surprised me. And those are the ones and the paths I’m usually interested in following. So I would say there’s sort of like, I mean, and there’s like a real intention as well. I mean, I don’t particularly feel that, like conventional society is doing a lot of wonderful things for the world. So, there’s a push against that as well and a desire to like push at the margins of what’s there and what’s possible, because so many other things are, in fact possible than what we could possibly imagine. And going down just one path is insane and damaging. And so there’s a lot of, I think, some elements of, of just wanting to push at the edges of possibility, because I think it’s necessary for like, human and survival on the planet.

Joshua Ferris 16:52

Yeah. So narrative, your narrative choices are determined by what you see in the world. How the world is going.

Angélique Lalonde 17:03

Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 17:05

Do you do…

Angélique Lalonde 17:05

And how that feels.

Joshua Ferris 17:07

What’s that?

Angélique Lalonde 17:08

And how that feels. And how that feels like on a on a human level. Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 17:13

Yeah. So that the narrative, does the narrative, the narrative does surprise you. And when you decide to ford the conventional mode, it’s surprising.

Angélique Lalonde 17:22

I don’t know if I actually know what the conventional mode is. I mean, I’m coming from outside of literature, right? I’m training as an anthropologist. I, I’ve read a lot, but I’m not, I’m not trained in literature. I don’t have like a, my reading is, my parents are both avid readers. There were books always in our home. But it was always based on proximity to whatever was around. And in a way, I’m like that too like, book spark, and I connect. So I don’t have like a, yeah, I mean, I don’t have the references necessarily, that someone trained in literature would have to know what the conventions are. So in that way, it’s like, a little bit of that as well I think.

Joshua Ferris 18:00

It’s true that Pooka was your first, the first story you ever wrote?

Angélique Lalonde 18:02

Yeah, no, no, no. I’ve written lots of stories. I’ve been writing for a long time. It’s the first story I ever published, that I tried to, tried to publish. Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 18:11

That you sort of brought out of obscurity of the, of the, of the desk and gave to the wider world.

Angélique Lalonde 18:21

Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 18:21

And, it won a, won a big prize. Not bad. That’s pretty good. Did you, you must have been, you must have felt pretty good about that and think well, I’ll do some more of these.

Angélique Lalonde 18:32

Yeah. Yeah, it was mind blowing. But I mean, it was such a boost to say keep going. Because I mean, I know that the stories are strange. I just, I didn’t know if anyone would want to read them.

Joshua Ferris 18:41

Yeah.

Angélique Lalonde 18:41

Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 18:43

Let’s, can I ask a refinement of the convention slash whatever the alternative to that is? Do, so, do you resist it? Do you think by, it sounds like you resist it more by instinct than by design. Like, that’s where your instinct leads you. Is that fair to say?

Angélique Lalonde 19:03

Yes. Yes. Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 19:06

So do you ever scrutinize that instinct and think, well, you know, like, yeah, the world’s going to hell. And there’s a lot of bad people and bad things. And everybody makes the same mistake over and over again, but well, why don’t I just throw my hat in with the world and write something very conventional? No, that never happens.

Angélique Lalonde 19:26

Well, no, I would never do that because I’m actually in love with the world and I won’t believe that it’s going to hell, I’m going to keep believing that there’s possibility for it not to. Yeah. So that’s my imperative.

Joshua Ferris 19:38

Yeah, I think that’s a good one. So, you know, they resist these conventions, but they could they would be immediately familiar to any contemporary reader. I mean, you’ve got dirty dishes and you’ve got beleaguered parents and emotionally unavailable husbands. You have a lot of emotionally unavailable husbands. Disappointed wives and mothers, you have a few of those, you’ve got those dickheads. You’ve got the difficult children, you’ve got rapacious and greedy men. So and you know, there are, there are video games, and they’re designers and smartphones and dating profiles and pregnancy tests and all sorts of like, just stuff of the world. But you know, if you if you read your, your bio, like I did, and then you, I don’t know where you live, but I always picture like a water pump nearby and foxes running across the window and, you know, creeks or whatever, right? I mean, it seems like you really live out there in the void. And so I’m thinking, well, how much of these elements are drawn from like, your actual lived experience on a day-to-day basis? And how much, you know, are you getting from the culture through just cheer osmosis?

Angélique Lalonde 20:57

Yeah, I mean, I think it’s a bit of both. I mean, there is a water pump and there, there are foxes in the yard. So you’re not that far off. But um…

Joshua Ferris 21:07

Are they working the water pump?

Angélique Lalonde 21:09

They kill the chickens. I haven’t seen that. But it doesn’t mean it’s not going to happen. So, yeah. Yeah. I mean, it’s both right. I mean, I, I’m a sponge. I absorb things. I participate in the world as well as, like, resist it to some degree. I mean, the dishes and all that stuff, like, yeah, I mean, I do a lot of dishes, like, we don’t have a dishwasher. We cook a lot of our own food. I mean, the dishes are overwhelming, I would love to have less dishes, but at the same time, I have to, like have this relationship with dishes. So I mean, it’s, it’s hilarious. I think of all these things that like we struggle against all the time. I mean, there’re there’re so right for, like exploring with story. I mean, we’re all living through these, these tensions, these constant tensions. And we can either choose to like suffer, or choose to, like, play with them and have fun or get curious about what they’re doing. So, I mean, I think when I write like, yeah, I mean, they’re funny. I mean, the fact that we do this as humans all the time that we agitate around these things is hilarious. So, so why not like bringing them into story is just sort of a way of exploring, I don’t know, those relationships and what they’re doing and what we’re doing. And so I think part of it is a lived experience, for sure. You know, like the pregnancy, the pregnancy test for instance, I did see a pregnancy test in the bathroom at Skeena Mall. And that is, that was like kind of like, that’s kind of original for a story, some of my stories, because I don’t usually, it’s not something that particular usually, but that one it was and so the story spun out from there. And so, yeah, and then some of them is just like, I’m really curious also about how how our, like, urban, like, technological world interacts with our sort of, like, sensory experience of the world. I mean, sometimes they’re so at odds, I mean, we get sucked into. I mean going to the city, for me, it’s like people are like, taught. I mean, you I think you call it the meme machine in one of your, in one of your books. Like, people are like sucked in, it’s like, it’s a bodily feeling. And I mean, I resist that, like I resist it wholeheartedly. I don’t want to meld with my machine. I want to meld with the world. So, but it’s not easy. I mean, when I went to the city for, for a week in Toronto, for the Gillers. I mean, I got, I have a smartphone and I had, I had to interact with it a lot more than I do in my life here. And I, and I understood, and then my sister and I were like together on our phones and I was like, oh my god, it’s happening. So I can really understand, you know, I mean, I’m sort of blessed and choose to live in a place where, where those bonds are looser. And so in a way, it’s easier to sort of explore the effects that they have.

Joshua Ferris 23:41

Yeah, there’s a subtle gradation of diseases based upon the addiction to the phone that we have yet to even, you know, scratch the surface of. You know, I mean, a reliance on them that bores deep into the psyche, and changes the fundamental nature of time, and erodes so much of the character in the soul and, and we’re not even really, we’re so, we’re looking at our phones so much that we don’t even recognize it. But yeah, it can be if you don’t resist it, it can be very overwhelming. I mean, I have friends, I have a friend who was such a raconteur. An incredible raconteur, who will, you sit down he’s telling his stories. He’s entertaining you. It’s like, no one hears from anymore because he’s glued to his phone. And it just seems like it’s truly the death of conversation it’s the death of…

Angélique Lalonde 24:33

Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 24:35

…Vitality. So well, anyway I don’t want to rant. Now I’m ranting. Would you do us a favour and read from, you’re gonna read from Malarkey, right?

Angélique Lalonde 24:43

Yeah, I’ll do I’ll do a little reading from Malarkey.

Joshua Ferris 24:46

All right, I’m gonna step out.

Angélique Lalonde 24:49

So I won’t give too much context here. I’m gonna I’m gonna read. I’m assuming that most of the people here have read the book. So you might be familiar with the story. So I’m just going to read the introductory passage to Malarkey that introduces us to the two main characters.

Marianne Thickenson is exploring her spirituality. She’s thirty-eight years old and childless, focused until now on making something of herself. Remaining childless and (theoretically) independent has given Marianne a lot of playing room in her explorations. For the last few years, however, her carnal life has become frenziedly driven by hormonal impulses quite different from those that made her want to rub her body against all sorts of soft and rigid things when her breasts plumped out and hair forced itself under the hitherto hairless body parts as an adolescent girl.

Back then it was all made sense of through romantic ideas about love and destiny but lately, there’s been an aching pulse in her womb that feels like a spirit trying to rip through the fabric of the universe seeking insemination in order to be made flesh.

Marianne wants to live rightly in the world but was not raised with any kind of guiding morality to fall back on with certainty; therefore she looks for guidance everywhere. From Marianne chance encounters offer spiritual revelation. She picks up cues from random conversations between strangers that she happens to overhear. Particular hot spots include lineups at the grocery store, the movie theatre, the credit union, the tire shop, cafes and bus stops. She also jots down quotes from radio programs, Instagram, and podcasts about books and the people who write them. Marianne makes her own interpretations.

Once she heard a woman with black hair and long red nails wearing dream catcher earrings talking to a boy about kindness she wrote in her journal:

Be nice to your friends, let it mean something. Be kind and good-hearted. Give lovingly without longing for return. Be kind to your friends, do not pull it their hair and kick them, offer them snacks just to take them back, or give them snacks and complain afterwards that they’ve taken from you.

Marianne holds fast to this. It allows her to go on living with Dev LaRue. If you asked her she tell you that she loves him like a sheep loves clover: wrapped into its tongue and pushed sideways, mashed into sweet liquid green and fibre in the crushing grinding teeth. Marianne wants to suck every sweetness from him, excrete the indigestible and little pellets that feed the soil so it can keep growing the goodness of clover on which they can both feed. As his sweetness passes through her, tingling her from the inside, she feels a sense of closeness with the goodness of God’s creation.

Stop there.

Joshua Ferris 27:53

That’s a wonderful reading. Thank you. Um, you, that’s just a terrific. I mean, that’s a terrific story. It is such a good story. And you know, it’s it’s about monstrous male obsession, and male myopia, which seem to me to be the twin engines by which this world runs. And, I know I’ve written quite a lot about it myself, I have never encountered a better document on those subjects than this story. It is incredible. What you managed to do in 30 pages and this is my question. The guy is kind of, I mean he’s a monster. But you never really stand in judgment of him. It’s, the story works in much stranger ways. I mean, for instance, you read us an example where she compares her love to the sun, the clover, this clover sucking by, you know, a wild animal. Like it’s very odd. It takes these odd turns and so forth. How did you, how did you not want to judge this guy? And how did you then also go into his world and give us so much of this comic book that he’s writing. This massive seven volume thing?

Angélique Lalonde 29:15

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think the, I mean what comes to mind, first of all, first of all, is just like, I mean, women love these men or men love the men but I’m writing from a woman’s perspective. And, and so what does that mean when you love someone that doesn’t see you and doesn’t know that you’re there most of the time. And yet there’s still your own, the agency of your own love and the power of that and so that’s what Marianne is sort of living with is this sort of, I mean, the reality of her own of her own form of love and and how it hurts and how it and how it, how it expands. And, and Dev like I mean, he’s existing most of the time through Marianne’s point of view so we never really fully see Dev as like a full agent. We sort of see him through Marianne’s perspective and then a little bit through his creation which he’s sort of melded himself into, because he doesn’t know how to feel. He doesn’t know how to how to feel the world, he knows how to, he drives himself into this into this fantasy. At the same time, as there’s this, this woman there that’s living with him and wants him to be drawn into a shared world somehow, and he’s not capable of doing that. And I think that’s the huge sadness of like, heterosexual, white male masculinity in our culture. Is that divorcing men from their feelings, from a very young age makes it very difficult for them to know how to be an intimate relationship with those around them. And that’s a, it causes suffering to themselves, and it causes suffering to those around them and those that love them. And so I’m interested in that tension, but ultimately, Dev’s still, like a beautiful human in the world. So to judge him is, would also notm not serve the purpose which is to explore Marianne’s love, which has meaning even if the love like, isn’t, isn’t coming back and or it’s coming back in a way that is ultimately harmful to her. And so we’re all engaged in these relationships all the time. I mean, I know so many couples that, that where this dynamic is living out, and I mean, certainly I’ve been in relationships that have caused more struggle than others. And so sometimes it’s not tenable. But, but yeah, and there’s something to be said that Marianne knows she doesn’t like, there’s some, a world that Dev has, that she can’t quite make sense of. And I don’t know if there’s, there’s no resolution to that. I mean, it’s an ongoing dynamic, right?

Joshua Ferris 31:49

Yeah, he’s…

Angélique Lalonde 31:49

Yeah, I think about it, too. Like, you know, I’m raising a son. And, and, and, yeah, so there’s a there’s there’s some element of think, playing through that idea and thinking around how that happens and where it comes from. And, and so maybe there’s that sense of not wanting to judge for that reason as well. I don’t know.

Joshua Ferris 32:09

Yeah, you don’t want to give up on the younger generation. Dev himself is probably lost.

Angélique Lalonde 32:16

I mean, Dev’s a monster, but I mean, monsters are also in some ways, there’s a part of them, that’s also lovable. I don’t know, maybe. Or at least Dev’s kind a of monstrosity who wants someone to love them.

Joshua Ferris 32:26

Well, you do something incredibly generous, which I won’t give away, at the very end. And it’s also an example of where you, you swore to what might have been the conventional ending. And you go into a fantastical, and yet it feels very real to me. Like what happens to men who are, who are more, much more interested in controlling their worlds and inviting something in that they can’t control is that ultimately, they live in that world. I mean, there’s no other world for them to live in, because they’ve sealed themselves off. And somehow you’ve managed to make this very real fact of the world and I know it from I know, I mean, I would like like to say that I’ve been immune from these sort of gestures. But I’ve, I’ve had to learn from my own mistakes in that regard. But I’ve also seen it in, like, amped up in within relatives and in friends. And, you know, and they end up being so very, very alone, that they do come to inhabit the world that they have made for themselves. And in their loneliness, find the kind of fulfillment and that somehow you’ve, you did it, you brought it together and ended it in this really fantastical way. But at the same time, which is what I find so beautiful about your work. Realistically, they dovetail beautifully in that story, and it’s really fantastic.

Angélique Lalonde 32:29

Well thank you. I’m glad it worked out.

Joshua Ferris 34:00

Who, like what writers or thinkers or artists shaped you as a as a human being and as a writer?

Angélique Lalonde 34:10

Yeah, I mean, there’s so many, so I need to like, take a brief. So I’ll go back. I mean, my first, the first books I remember falling in love with were Calvin and Hobbes. I think I was probably like, I don’t know, maybe in grade grade three or something. And I got one at a book fair at my school. And then I had to get all of them. So that was, that was the first like rabbit hole I went down. And then embarrassingly enough it was then Sweet Valley High in high school. So that was a really, totally like, not in any way connected to my life growing up in a coal mining town. But for some reason, the formula worked and I got really into that. Yeah, and then yeah, and then I kind of moved away from the coal mining town and went to university and then people were reading other things and sharing those things. I mean, I love Kofka. That was like, that, like kind of blew my mind the first time I read one of his stories and I was like, whoa. Okay, so we can do this with a story. All right, let’s go with this. Um, I loved, and then I fell in love with the poet Marina Tsvetaeva, the Russian poet and went like down like a Russian romantic phase for a while. I tried to learn Russian, I studied it for a couple years, and then realized like that it was going to take a lot of work to get to a level of proficiency in reading Russian that I would actually be able to read her poetry, and then other things sort of, kind of happened in life and I and I didn’t continue. But I, so that was something of an influence. And yeah, I mean, I love Ursula Gwynn. I’m kind of like obsessed with Mary Ruefle right now. There’s, and then there’s so there’s so many things, but that’s sort I guess, where I’ll leave it. And I mean, I’ve read a lot of anthropology and anthropological theory. And I, and I’ve, I can’t like pick out anyone now cause it’s been a while, but I mean, that shaped me a lot. And shaped my thinking. But I’m kind of yeah, um, and Bell Hooks who just passed away was also pretty influential thinker for me.

Joshua Ferris 36:14

Those are good. Those, those will make for life I think. That’s good. Um, do you have a favourite story in this collection?

Angélique Lalonde 36:24

No, I don’t. Um, I mean, I think they’re all, yeah, they all come from different feelings and moments and, and curiosities. I mean, I think, two kind of stand out as like, like The Leopard in the Bathroom, which is a really short one. I feel like I did that, like that one to me, like, got done in such like, small amount of words. I felt happy and excited about how quickly I could write that story and feel like it could be contained. And it’s, in a few words, and then The Lady With the Big Head Chronicle, it was an interesting, like, took me on a big journey. And in fact, she’s reappeared. I thought she was like closing her story but she’s decided that I should keep writing about her. So, so she’s continuing to do things. But I have a relationship with all the stories. And I can’t say that I love one more than the other.

Joshua Ferris 37:16

I feel the way you’ve described The Leopard in the Bathroom, about um… Which story is it? Hold on. A home for secrets. Because that is also very, very concise. And seems to not have one extra unnecessary word, gets in and out very quickly. It’s probably what maybe three pages or something. That’s a really special story. Does one standout in retrospect, as harder to write or even maybe there was one that was super easy to write than the others?

Angélique Lalonde 38:00

Yeah, um… I mean, Pooka was hard to write because it explores some, you know, addiction, and some pretty like, devastating life circumstances. My eldest sister is an addict who lives, has lived a, I guess, is now estranged from the family and, and I wanted to write something for her children. And think about. Yeah. Think about, I was thinking about that in that story. So that story was hard for me to write.

Joshua Ferris 38:40

On a lighter note, did you think that once you put them into a collection that you would be nominated for a Giller?

Angélique Lalonde 38:45

No, of course not. No, I had no idea. I mean, I knew early on in the conversation with my publishers that they were going to, that it was going to be nominated so, I was, I knew that part of it. But I mean, that it that it appeared on on the list. Yeah, I mean, it was it’s all been a huge surprise.

Joshua Ferris 39:03

Yeah. Good one. I’m going to ask you one more than we’re going to ask some q&a questions. These stories, have, you know, these familiar enough settings that we talked about, and you touched upon it in Malarkey, right? She’s standing in the bank and shoe store or whatever. But often they take the reader into these liminal spaces as well. These divides are like these shimmers between the physical and spiritual realms, the animal and human. Into the imagined and the real. When I read the book, I thought this like this very numinous presence, in many of the stories as if they were on the brink of like genuine revelation, which is very rare. Maybe you want to take full credit for that maybe you don’t maybe want to think or that comes from somewhere else. But in any event, can you speculate on where these impulses originated? I mean maybe it’s, you’ve talked a little bit about being connected to the land and living very close to the land. Maybe that’s where the [inaudible]. Are these, I’m also interested to know how hard they are to try to capture in words because they they exist in another world that’s hard to articulate everything.

Angélique Lalonde 40:15

Mm hmm. Yeah. I mean, the stories come, I mean, I feel like they’re gifts that I show up for and that I opened myself to being in the space to write. I, I don’t, I mean, I often I don’t, I don’t have any idea at all what I’m going to write. I sit down, and then like a sentence comes, and then the story goes from there. And then everything emerges. So I’m, I’m learning by writing, I’m experiencing the world, in relationship as I’m writing. So there’s sort of like the the physical experience of being in the world, but then it would feel for me, not fully experienced if I wasn’t writing about it. And so the writing is a way to sort of, I guess, process or be in relationship to those experiences. So all the things that come in, and these stories are what emerged. And I mean, I think the world is magical. I mean, there’s so many things we don’t understand and can’t possibly comprehend. And, and human, like beings, throughout time have had so many ways of understanding and making meaning in the world and being in relationship with each other. I mean, there’s magic in all of it. And and we’re influenced by it constantly. You know, like, I mean, if you have spent any time with children, it’s, we spend all this time teaching these magical worlds to children and then like, as though we were supposed to grow up and then come out of those like, I guess I just haven’t, maybe I haven’t fully grown up? I don’t know. And I hope to keep it that way for a really long time.

Joshua Ferris 41:44

Yeah I do too. It’s hard, you know, especially when you have all those dirty dishes, and you want them to do it.

Angélique Lalonde 41:51

Yeah, right. But you got to just turn them into magic, too. I mean, I don’t always manage to but sometimes, sometimes.

Joshua Ferris 41:57

Yeah, my failure rate is probably pretty high. But in any event, it is a magical thing. You’re right, I mean, to watch a child that, at work, because it’s serious work. It’s play to us, but it’s real serious to them, and to see how serious they are. You can see the translation into adulthood, it has less to do with the, you know, less to do with the the object and the continuity of their mindset. Because it’s the same work that they’re, you know the same expression and the intensity, when they’re looking at these games that they’re inventing. And then, 30 years later, the P&L reports from Nabisco or whatever the hell that they’re, you know, been paid, the paid to scrutinize, or whatever their accounts do. And, you know, I mean, it’s like the same, the same person, but just different objects. But it hasn’t the magic of childhood is that they’re the same. I mean, I can think back on, you know, having that kind of intensity for Ernie and Bert and baseball cards and other things that now I think of when I, you know, read books and write books. Well, let me turn to the audience q&a And see if we have a question that’s not profane and make sense. Let’s see. “Are you also writing these..” this is from anonymous, they didn’t want to be known they wanted to leave themselves out of this conversation. “Are you also writing these stories to your children?”

Angélique Lalonde 43:28

Hmm. I don’t think so. Because I can’t conceptualize what my children will be like, as adults and, and they won’t be ready to read them for a long time. So I don’t, I think of, so I don’t really think of them when I’m writing, although I suppose I’m influenced by them constantly. So in some way, they’re there, but not in a way where I’m thinking about the stories for them. Mm hmm.

Joshua Ferris 44:00

Do you think they will read it one day?

Angélique Lalonde 44:04

Probably, I mean, I don’t know. They might be totally uninterested in what I’m up to. I mean, they think it’s interesting. My daughter pretends to write books, she sets herself up an office and, and she, she like, makes the book sometimes. And she says she’s going to Toronto and puts on my shoes. So, yeah.

Joshua Ferris 44:21

Well, that’s cool.

Angélique Lalonde 44:22

I expect they might at some point, become interested in their mom’s inner world but for the most part, children are not interested in their parents inner world, which which is okay. I don’t need that from them.

Joshua Ferris 44:34

This is another one from anonymous, maybe a different anonymous, maybe the same – we’ll never know. “Was it a deliberate choice to make all of your narrator’s women and the last one male?”

Angélique Lalonde 44:44

No, it wasn’t. And I don’t know that the narrator in like, Ropes of Entropy is is a woman. So I don’t think all of them are. I think a lot of them are. Um, I mean, it’s just my that’s my, you know, tends to be my experience of the world so it’s it makes sense to write from there. But no, it wasn’t deliberate to arrange it like that.

Joshua Ferris 45:09

Reva Nelson asks, “Your titles,” or states, “Your titles are hilarious, intriguing and weird. I bought your book because I loved the title. Do they pop into your head easily? Do you laugh at them also?”

Angélique Lalonde 45:23

Yeah, for sure. I mean the, the title for the book came at some point pretty early. And I knew that that’s what I wanted it to be. And some of the [inaudible] titles. Yeah, for most of the stories. I like to make myself laugh. So thank you. I’m glad you find them funny too.

Joshua Ferris 45:35

“I understand,” this is from Louise…. I can’t see with my glasses. Louise. Louise Kilby. Who says, “I understand you live on,” oh, I’m going to botch this. Americans can’t do this, Louise. Gitxsan Territoy.

Angélique Lalonde 45:54

Gitxsan. Gitxsan.

Joshua Ferris 45:58

In the Kispiox…

Angélique Lalonde 46:01

Kispiox.

Joshua Ferris 46:02

Kispiox Valley. Thank you. “Can you tell us about the community development that you’ve been involved in there?”

Angélique Lalonde 46:09

Ah, okay. Well, I have until recently been working for a non-profit organization called Storyteller’s Foundation in the community. I’m not going to talk about that too, too much, now. Because it’s kind of pretty separate from my writing. But the the living on Gitxsan Territoy is a big part of my experience. I mean, I’m here as a non Gitxsan person and always profoundly aware of like, the colonialism that has brought me here and the relationship that I have with the land, and how I’m uninvited on the Territory. And that there, the, the territory is storied and alive through a culture that I’ll never be a part of, and that a community that has suffered a lot from and from other people, folks like me being here. So that’s always something I’m aware of in my, my relationship with land and how to have that relationship. Knowing that these things are, are here and at play. So yeah, I, I guess that’s sort of where I’ll leave that. And if someone is more interested in finding out about the work of Storytellers, they can they can look that up and get in touch with some folks there, I’m not there anymore.

Joshua Ferris 47:23

You have a restless, like, an a kind of almost obsession to to like bringing out or at least discussing alternative stories, stories of worlds that have been lost, stories about worlds that have been foreclosed due to greed or mismanagement or whatever. Is that tied into the way you’ve just been saying about the land and, you know, being uninvited, searching for alternative ways of thinking about the world?

Angélique Lalonde 47:55

Sure, yeah. I mean, my mom is, my mom’s family, you know, we were, we were brought up being told we were Métis. It seems now, like, I’ve, now that have a much bigger understanding about who the Métis people are, and the Métis Nation, and folks from Quebec, identifying as Métis being a sort of a, not like sort of a damaging to Métis sovereignty. I don’t say that anymore. But my mom doesn’t know what her background is. She left home as a as a young person. And so I don’t know what my relationship to her indigeneity is or what her relationship is. So, it’s part of my own life experience to have these questions in my mind, and these displacements and the loss of culture, the loss of story, the loss of place, the loss of belonging. They’ve all been there from the get-go. So I think about them all the time. At the same time, yes, I guess, as an anthropologist, too, I spent a lot of time thinking about some of the some of these some of these things in a more academic way. And now I’m more interested in how they can come out as stories so that they can I guess, potentially be shared with a wider audience than, than what is possible in academia.

Joshua Ferris 49:13

Kelsey Lavoie says, “Thank you for your book. PS I love the shape size…

Angélique Lalonde 49:18

Kelsey, Kelsey’s my pal. Sorry, continue.

Joshua Ferris 49:21

She, she differs with my opinion on the… I like the shape now! I just didn’t at the beginning, Kelsey, so I’m with you, I came around to your point of view. Question about your process. “Really appreciate your connection with love, loving the world and finding ways to see the loveable parts of seemingly monstrous beings. Welcoming complexity and strangeness seems to be a way into love. Wondering if you have to work at being this welcoming. Or if that is something that just comes as the characters and stories emerge or come through you.”

Angélique Lalonde 49:51

Oh, I have to work at it. It isn’t easy. Yeah. Yeah. And the characters are easier to love than real people. So, yeah, I think it’s an ongoing task to set oneself to.

Joshua Ferris 50:07

It’s a worthy task. Yeah. It’s a hard one. I mean, I, you know, I just wrote a whole novel, about my father and only, like, I spent like four or five years doing it. It’s only like, in the last year that I had to realize that I hadn’t even imagined him. You know, sometimes the further you get into a story, the more you think about it. The more you get lost, to the very fact that there’s just some other consciousness you’re writing about when you write another character. It’s very, very hard to access that person unless you really try. I mean it’s, maybe it’s just me, I’m having inordinate limits to my imagination into my empathy. But I, I have to work so hard just to get somebody else’s perspective on the page. And I think, my god, if that’s what I do for a living, imagine somebody that that just does, never even thinks about that. Like, it’s so very, very impossible, so hard to do. So, it does take work, even for the likes of the story writer.

Angélique Lalonde 51:09

Mm hmm. Yeah, for sure. And I mean, some, some of the characters I can’t quite get to as deeply and so they stay minor characters, and, and maybe later, I’ll be able to more. And I think, yeah, but I do think about that. I mean, some, some characters are just easier to write because it’s more familiar to me and those that are, are less familiar, it’s harder for me to write them, which is also part of the reason why I think I can get more, go more deeply into, like, into female characters. And because that’s closer to my experience.

Joshua Ferris 51:43

Rebecca Evans asks, “Can you describe how your anthropological studies have influenced your writing?”

Angélique Lalonde 51:49

Yeah, I don’t think I can do it succinctly. I, I’ve kind of worked working on a sort of non, I’ve worked on a non-fiction book that sort of explores that a lot. I mean, I think the main thing about anthropology and maybe why I was drawn to it is just like, it makes you got to be curious about things beyond yourself and other possible realities. And, anthropology teaches you, I mean, it’s got if nothing else, that reality is, is all made up, that we make up reality in really different ways in different cultures. Which isn’t to say that there isn’t structures that determine what our realities are. Because there are and what are what’s possible with our realities, but I mean, we are actually, have made up so many, like, impossible things throughout time as humans, and will continue to do so. I mean, we can’t imagine a world beyond the one we know, but it will come. And maybe we can imagine it. That’s what we’re doing when we’re writing all the time. And, and so, maybe that’s why I like writing and because it allows me to play with the made up in a way. But yeah, I mean, there’s there’s such a diversity of, of experience, and even just the things that we essentially experience in the world, depending on what kind of culture you grew up in, and what kind of way you attune your body to the world. So, so I think, I think I explore some of those things and want to continue to explore them in my writing. And I think in that sense, it has has been influenced by a sort of like anthropological thinking about, about what humans are and what they’re in relationship to, and sort of what forces influence those relationships. Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 53:23

All right, you did that succinctly enough, I thought. I have, let’s do one more. And then we’ll get Daphna back and call the night. You’ve definitely worked for your dinner here. Margo Matwychuk says, I wasn’t, I’m sorry, if I’ve slaughtered your name, Margo. “I was impressed with your ability in the pregnancy test to tell the stories of women from such different places, and ways of being with such care and honesty. Did you have particular women in mind when you when you wrote those stories?”

Angélique Lalonde 53:56

Ah, hi, Margo. Um, ah, let me see some of them. Yes, yes. I did now that I think of it. Yeah, they’re coming up a little bit for sure. Yeah, I did have some different women in mind when, and I’m so fond of all of them, as well. Yeah.

Joshua Ferris 54:16

Well, there it is. Um, I just want to leave you with the strong exhortation that you must write more books. I just love your books. I just love it. And, and I can’t sing its praises high enough and hope there are many more to follow.

Angélique Lalonde 54:36

Thank you. I’ll, work at it.

Joshua Ferris 54:38

All right. Daphna, you want to come back and say good-night? There she is.

Daphna Rabinovitch 54:45

Sure. I’m right here. Hi, guys. Oh, my gosh. I can’t thank you enough for both, both of you for joining us tonight. I just have to thank you so much for dedicating your time and your insights and your thoughts for questions. Thank you so much. And thank you all as well for joining us this evening. I know you’ve probably enjoyed it as much as I did. Two remarkable people, two remarkable writers. This interview will be available on our YouTube channel during the next couple of days. So if you know anybody who missed it and wants to see it, it will be available there. And I want to invite you to join us on February 22, for our next book club, where Donna Bailey Nurse who’s an author and a literary critic, will interview Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia for her shortlisted Giller title, The Son of the House. So if you subscribed to our book club mailing list, you’ll get a notice to register if not, just visit our website. And I look forward to seeing you then. Thank you have a great week. Have a great evening or an afternoon if you’re on the West Coast. Bye!

Share this article

Follow us

Important Dates

- Submission Deadline 1:

February 14, 2025 - Submission Deadline 2:

April 17, 2025 - Submission Deadline 3:

June 20, 2025 - Submission Deadline 4:

August 15, 2025 - Longlist Announcement:

September 15, 2025 - Shortlist Announcement:

October 6, 2025 - Winner Announcement:

November 17, 2025