[Video] The Giller Book Club: The Listeners

[Video] The Giller Book Club: The Listeners

March 9, 2022

Daphna Rabinovitch 0:00

Good evening everyone. My name is Daphna Rabinovich, and I’m thrilled to welcome you to the 2022 Giller Book Club. This is the fourth book club this year and I want to ask you to please make sure to have your Zoom on a side-by-side review for the best possible experience. Tonight it’s my profound pleasure to introduce you to our interviewer, Jael Richardson. Jael is the Executive Director of the Festival of Literary Diversity. The book columnist on CBC Radio’s q, and an outspoken advocate on issues of diversity. She’s the author of The Stone Thrower, A Daughter’s Lesson, a Father’s Life, which is a memoir based on her relationship with her father, CFL quarterback, Chuck Ealy. The memoir, received a CBC Bookie Award, an Arts Acclaim Award and a My People Award and a children’s version was published by Groundwood Books. And, you know, we were talking earlier and she was told by Facebook this morning or something today that it’s the 10th anniversary of her signing her very first book deal. So, that’s, that’s quite an accomplishment. I also want to say that her essay Conception is part of Room Magazine’s first women of colour edition, and excerpts from her first play, My Upside Down Black Face appear in the anthology T-Dot Griots: An Anthology of Toronto’s Black Storytellers. And her debut novel, Gutter Child, was published in January 2021, by HarperCollins Canada. It’s a dystopian tale of courage and resilience. She also received her MFA in creative writing from the University of Guelph, and she now lives in Brampton. And tonight, Israel will be interviewing Jordan Tannahill, author of the novel The Listeners, which was shortlisted for the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize. He’s actually joining us from Senegal, where it’s about one o’clock tomorrow, in the morning. Anyway, over to you, Jael!

Jael Richardson 2:27

Thank you. Thank you. Hey, Jordan. So, Jordan is joining us from Senegal. I’m probably most disappointed, Jordan not being in person because Jordan is known for the most fabulous outfits and so, I’m disappointed in particular, that I don’t get to see the full thing, you know?

Jordan Tannahill 2:46

Pretty basic tonight, but it’s so lovely to see you nonetheless halfway across the world.

Jael Richardson 2:52

It’s so great to be here. For those of you who don’t know, Jordan who have, or who have only known him from his books, a little bit of background. He is a Canadian playwright as well as a novelist, two of his plays won the Governor General’s Literary Award for drama, his debut novel Liminal, which if you haven’t read, grab it, was named one of the Best Canadian Novels of the Year by CBC Books. He was born in Ottawa, lives in London, England, and as you heard, he’s joining us from Senegal. So, you know, I think he has more places in his bio than I’ve probably been life. So, this is great to talk to you, to be able to connect with you here. I know you’re outside. So I love that we can, we can chat with you and just imagine being somewhere else, for many of us. How are you? How is it there? How are you doing today? Tonight, this morning?

Jordan Tannahill 3:43

Yeah, it’s so lovely. It’s so lovely to have this hour together. And, I am well, I mean, we might hear some outdoor sounds and dogs, etc. So I apologize if it’s distracting at all, as we chat. But, but it’s lovely here. It’s warm. And and yeah, speaking of sounds, we’ll be hearing some, you know, speaking of hums and tones that, they’ll definitely be some, some, some SFX. I think as we talk.

Jael Richardson 4:10

I love that. I love that. It’s fitting for the book, right? You’ve got to listen, pay attention to what you’re hearing, maybe some people are going to hear dogs, some people are going to hear cats. It’ll be a controversy of its own. Okay, I want to get into the book that I’m, and I will say I’m assuming most people are tuning in have read the book. And so, later on there will be some spoilers. So, that’s just a heads up. But I want to start before the book, I want to start with a fact, you know, we’re both drama nerds. We both started sort of in that area. I know you’re a playwright and a theater geek. And so I’m curious what made you transition or what made you approach prose and longer works, novels in particular, given that you have this very live theater background and experience

Jordan Tannahill 5:01

Yeah, it’s a great question. I mean, I think when I began working on on Liminal, my first novel, I had been, first of all been reading a lot of sort of autotheory and a lot of autofiction. So a lot of like Mike Nelson and Ben Learner, and a lot of the great French, you know, like Jean Genet, and Margaret Duras, and just really loving the kind of intimate, long form relationship that you can develop with, with an author or with characters that prose allows. And, I never really sort of set out to write a novel, per se, I was sort of writing what felt like collection of sort of personal essays, or, or a sort of autotheory, I guess. And then began sort of finding ways to kind of link them through narrative. And it was really kind of late in the process of writing all this material that I was like, maybe this is a novel, like, you know, and then and then really began conceiving it as a book, as a big project. And so I kind of sort of backed into writing a novel a little bit with what, you know, sort of like with my eyes closed a bit or sort of stumbled into it. And in a similar way, I think with with The Listeners, I actually initially began conceiving as a play. I guess, as you know, being a playwright primarily, that’s kind of how a lot of new ideas initially sort of present themselves as possible plays. And I soon became, well, it didn’t seem become clear, actually, it was quite late in the project. I had to work on this thing, before it became clear that it wasn’t a play, I actually wrote this play. And it was like, four hours long, it was like this epic State of the Nation play. And when I say that, I mean, it was just like, you like 20 characters, and you know, and, you know, and it was actually written for the National Theatre in London. And we did a workshop of it, we actually kind of, like, there was actors in a room reading this material. And it was, it was amazing, but it like, you know, it was like, it doesn’t make sense for it to be this like, to park Angels in America, like it doesn’t like, the material doesn’t lend itself to, like, you know, now you have to come back tomorrow night and watch another two hours, you know, it just doesn’t, it doesn’t make any sense. But I know, in order to kind of cram it all into one night, it would have had to really, I think it would, a lot of material would have been stripped away from it. And so what I think is a kind of fairly sort of, you know, complex journey that we follow Claire on would have been, I think reduced to kind of like a, you know, downward spiral narrative, or just a cult narrative, or, you know, it kind of would have felt a bit pat. And so I think the novel, you know, affords a lot and one of them also, I think what’s so key to this book, is the kind of the deep interiority, of inner monologue that we can really get into, you know, get into clear psychology, through prose in a way that you really can’t, in the more kind of external form sort of the live form of theater, which, of course, has many other amazing things. But the kind of, that sort of protracted interiority was really, I think, what unlocked the storytelling for me and what allowed it to work in prose. And yet, all these character voices are also very present. And they were, you know, I think honed and refined in the room with with actual actors. So, in a way, I sort of have taken on some of the, you know, carried forward some of the skill sets or tools that I love about writing dialogue, and character voice and syntax, and applied it to the novel.

Jael Richardson 8:17

I cannot believe so we, I’ve talked to you numerous times about this book, because I was obsessed with it from the first time I finished it, I like wrote to you, like, I love it so much. I can’t believe we have not talked about the fact that it was made into an entire play with actors reading the lines, and then turned into a novel, especially because I’m like, as a theatre person, I know how much work goes into a play, to casting to those kinds of like, live readings to take all that. How hard was it to say, Guys, I’m out! This is a novel and you’re all done.

Jordan Tannahill 8:49

Yeah, well, that’s the thing. It’s, you know, it can be so hard sometimes to say, this is not right, or this is not ready yet. You know, and to say, you know, to kind of actually sort of kill a project and know that it has to be remade or reformed. And I think that comes with, you know, with knowing what, what works on stage and what doesn’t, and what works, maybe like, it takes some experience. It was really hard to kill it, that project because it had been something I had been working on for, like two or three years at that point. And it felt like, it felt like a bit of a failure, like, oh, I wasn’t able to manifest or realize this, you know, what would have been my first major, big major new production, you know, certainly in London, and I felt like I’d sort of wasn’t able to kind of, you know, it was a big opportunity with the National Theatre, I wasn’t able to kind of make it work. And yet, I knew that the story was still really special and something that I really wanted to tell and, you know, for, I know, we’re all Canadian, you know, CanLit geeks on this, on this call, on this lecture, or a talk rather. And so, you know, I think some of you will really appreciate this kind of like CanLit backstory. Some of you are probably aware of this already that Ann-Marie MacDonald, who of course, is another great playwright, turned novelist and you know, remains a great playwright as well. She initially wrote Fall on Your Knees actually as, or attempted to write a huge epic play version of Fall on Your Knees. And I think as she was beginning to work on this play, it became, you know, became so evident that it was just too big for, you know, the container of a live performance to hold, at least initially. And thenm she eventually made it into her acclaimed novel. And so what is so kind of fascinating now is that many years later, after the great success of the novel, Hannah Moskowitz who is a wonderful playwright, a Canadian playwright. She’s actually worked with Ann-Marie now to adapt the novel back into a theatrical form and is now actually going to be four, a four-part theatrical epic that is being staged by major theaters across Canada, including the National Art Centre. So, it’s yeah, it’s kind of funny how that great story, that great narrative that we all know and love, began sort of in its, was initially conceived for the stage didn’t work, became a novel worked exceptionally well and is now being reimagined back into its, into a theatrical form. So it’s funny how these things can kind of…

Jael Richardson 8:50

Yeah, they change and move. I think it’s such a great redemption story too, in a way, right? You think that it’s, it’s kind of failed, it’s kind of dead. And then it actually like rises from the ashes on the Giller shortlist, which is amazing. So, I want to take a minute before we get into questions, specific to The Listeners to just hear you read from it. I love the idea that we’re going to listen to The Listeners. And so I’m going to turn off my video, I’m going to listen along with everyone and then I’ll be back to asking questions.

Jordan Tannahill 11:39

Great.

Before this, I had never considered all of the unknowable sounds in the world. Sounds we could only see graphed or mea – sured. The deep sounds of the Earth that no one hears. The erup – tion of volcanic vents thousands of metres below the water. The scraping of icebergs along the ocean floor. The mysterious bursts and burbles of the Earth that even science couldn’t fully explain. The skyquakes that boom like cannons on calm summer days over the Bay of Fundy, or cause kitchen plates to rattle on Lough Neagh in Ireland. Or the gas escaping from vents, from vegetation rot – ting at the bottom of lakes or released from limestone decaying in underwater caves; the explosive and volatile digestive system of the Earth, bubbling, burping, expelling. The concussing of continental shelf fragments calving off into the Atlantic abyss. The roars from solar winds. From magnetic activity. From avalanches. From distant thunder that, through some anomaly in the upper atmosphere, managed to throw its voice across valleys, across mountain ranges to different cities and different states.

Before this, sound was something I took for granted. It was always there, providing pleasant texture and useful information to my day-to-day life. I liked music, but I have never been an aficio – nado like Paul. I could never tell the difference between the sound quality of a CD and a record. But once this all began, all I could think about was sound. And not just my sound—for I came to think of it as ‘my sound,’ as if I owned it, or it owned me—but the mysterious dimensions of sound more generally.

One night, after Paul had already gone upstairs to bed, I was sitting with my laptop in the dark of the living room. I googled ‘most beautiful sound in the world,’ and spent an hour listening to frogs singing in a Malaysian swamp, the cascades of the Neretva River, the chirruping of thrushes at dawn, the wind whipping itself against an ocean cliffside in Sonoma. But when I thought of it, the most beautiful sound I had probably ever heard was a lawn mower. When I was a girl, lying in the hot summer grass of my grandma’s bunga – low, listening to the sound of her neighbour cutting his lawn in the distance, I remember feeling like I would live forever. The purr of that lawn mower, three or four houses over, was like the sound of eternity itself. Sitting there in the living room, it occurred to me— the entire story of my life could be told through the sounds that have surrounded it. A continuous forty-year playback. A biography of room tones, bird calls, pop songs, voice messages, laughter, train whistles, dog barks, and wind moving through innumerable leaves.

Thank you.

Jael Richardson 13:50

I love it. Every time. I love it every time. I want to for those who may not know and well I definitely didn’t know until I geeked out and asked you so many times. But can you tell us a little bit, this is based on a true story. So can you give us a little bit about that original event that kind of inspired this and what you learned before you even started writing that’s kind of fascinated you about this early 1970s story.

Jordan Tannahill 15:08

Yes, yeah. So I’m just, yeah for some context, in case, for those haven’t read the book. But you know, in a nutshell, the book follows a woman named Claire who begins to hear this low frequency hum, that no one else can hear in her in her family or among her friends. And it begins to sort of shift her entire life and her sort of belief structure, as she falls in with a group of people who also can hear this hum. And the idea for the story, it was based on an actual sort of phenomena known as “the hum.” And the hum is a disparate series of 1000s of cases reported of a similar sort of unknown or untraceable, low frequency humming sound that people have been able to hear around the world in, in sort of localized clusters since roughly the early 1970s. And there were a number of, sort of, there’s, you know, quite sort of arresting cases of people hearing this, this noise, and it’s sort of localized, as if it’s sort of kind of localized instances. So for instance, in the 70s, in Bristol, in the UK, there was, you know, quite a, an outbreak of reports of this noise and two local suicides were actually ultimately attributed to people who were, you know, driven to have insomnia and sort of driven to sort of, you know, yeah, to take their own life because of the amount that weared on them. And so the book, sort of looks at the ways in which the sound does have this adverse effect on Claire, and how she, how she deals with it, and how she kind of ultimately finds this, you know, sort of finds the sense of community and also the sense of kind of, really kind of rapture with this, with this noise. And I think, when I first kind of heard about these, these cases, and this phenomena, I was, I guess, struck by the ways in which it kind of speaks to our desire to believe or inclination to believe in that which is not always supported by evidence or facts, and the ways in which this kind of seemed to touch upon a number of, I think trends that I think I feel like I’m quite curious about at the moment. Everything from conspiracy culture to, you know, faith, why we believe in what we do, and, and sort of the nature of community and ritual and how we kind of build narrative. And so, yeah, so I think that the piece is, in some ways, kind of looking at yeah, sort of faith, mania, conspiracy culture. With this, you know, this, this kind of this, yeah, this real life phenomenon.

Jael Richardson 18:01

I loved it. I mean, having grown up and still in, like a faith-based culture, where sometimes I’m like, whoa, y’all are, have lost it. And sometimes it’s been like a very, like, leading source for me. I found, I found it so fascinating. I mean, I find conspiracy theories fascinating in general, as well. And I was really interested in particular, because I think we’re going through a particular moment where conspiracy theories and sort of wild narratives have really taken a life of their own and and been a big part of the conversation. And like, a weighing part of the conversation, for lack of a better word. And I was I was wondering how much the conspiracy theories that the narratives that were maybe not rooted, in fact, over the last two to four, five years, how much that shaped the approach you took to looking at this conspiracy, whether, whether it changed from because I imagine, well I know, because you were working on for so long, right? You would have been working on it before it became, you know, there is a particular political figure that like drove many narratives of conspiracy.

Jordan Tannahill 19:13

Yeah.

Jael Richardson 19:13

And so I’m wondering how that that changed as you’re working on this, and as conspiracy theories are playing such a major role in major narratives, how that changed what you were writing?

Jordan Tannahill 19:23

Yeah, for sure. I mean, I think yeah, when I began working on the book, I was sort of really interested in this idea of the malleability of truth and how we sort of answer the nature of the citizens, question whether truth is objective or whether it’s objective. And then and then yes, I mean, the sort of political mainstreaming of conspiracy culture and particularly like QAnon and sort of use various kind of these theories that were sort of, you know, birth in the nether regions of 8chan and 4chan these sort of these online, you know, sort of posting sites, message boards, message board sites, how they began to really filter into the mainstream of political culture was so fascinating and certainly very scary. And, that that, I think that is, you know, the, is fused through the book for sure. And in fact, in the copy editing process, like, while we were sort of working on the on the copy edit over the UK, there was stories, you know, headlines talking about people bringing 5G towers because of their, their possible link to COVID and you know the spread of COVID. And it’s so funny, because actually, in the book at one point, Claire does vandalize a sort of cell tower, a 5G tower in her neighborhood, thinking that is part, you know some kind of possible link to the hum. And so I think, yeah, I think this sort of this, this, you know, we are in a very sort of this low trust moment, at least America has a very low trust moment with its, with its kind of civil society and the sphere of the deep state, which I think is both sort of found in some ways, but, you know, but also, not in the ways that often that the conspiracy culture tends to constructed as. You know, I think this, I mean, we do live in it, you know, we do live in a moment of deep surveillance, and I think there is sort of value in being, and being sort of cautious and wary about, you know, about about that but I also think it’s, we’ve, we’ve, we’ve really lost a kind of sense of trust of expertise, of science, you know, and I think that’s a very dangerous thing. And I think the malleability of truth is something that really Trump kind of learned from the Putin playbook. And, you know, we’re of course, see how that’s unfolding at the moment. And so, you know, I mean, I think, when truth begins to become eroded. Many democratic institutions do as well. And so, you know, the stakes are very high. And obviously, this book doesn’t take on all these great themes. But it does sort of look at it, how it plays out within it. So the microcosm of a family and a community, and how it erodes the foundations of kind of a marriage and, and in this case, Claire’s life, really, but she also, as you said, you know, while there can be sort of, you know, kind of these, I suppose, dangerous aspects to the nature of fervor belief that maybe it’s not even sort of often supported by backed or, you know, or what we would consider logic, there’s also this very deep human impulse that needs to be sort of satisfied for Claire, which is the sense of like, you know, what, there is something that is also beyond her, beyond reason, beyond logic, that is a very powerful force for us that, you know, that we that we seek to kind of be in communion with. You know, and that and that is, for some people is kind of spirituality or it is the ecstatic or it is the sublime, and within the hum, Claire locates, that she locates the sense of, you know, of actually, if I transform my relationship with his hum, it’s not actually something that oppresses me, and wears me out and, and prevents me from sleeping and causes me to have migraines and nosebleeds but actually, it’s something that if I tune myself to, this is, this for her becomes as the others in the group who believe this, the vibration, the resonant frequency of the Earth itself, and it actually becomes this very powerful source of, of communion of, of ritual for them. And, and for me, that’s based, I mean, I grew up in two different religious households. My father and his family is very Lutheran. I was really raised within the within the Christian faith. My mother is a devout Buddhist, and she practices Nichiren Buddhism. They are separated. But they’re both very devoted in their own, you know, in their own households. And, and, you know, growing up with my mom, you know, I would hear her chant every morning and every night, the Nichiren Buddhist chant as a means of communing with the universal life force and through sound, communing with you know, connecting themselves with that, with that, lifeforce. And, and, and so that and then, you know, would kind of oftentimes, once or twice a week would gather at my mom’s house, a group of six, seven, eight people, nine people, not dissimilar from the groups, the group in Howard and Jo’s house. And actually I realized this after I’d finished writing the book, like oh my god this is actually, I kind of grew up this group, like, in a way people and people, you know, like chanting together for an hour and then talking about their lives and, you know, in a kind of, sort of, you know, sort of like a, it’s almost like a therapy circle, but in a way that was, you know, I could really see true benefit in you know, I see how my mom’s practice has really shaped her life and strengthened it and viewed with immense meaning, and the community, as well as she’s found is, has been, you know, a credible life source. But it is interesting that I, you know, I’m, like, like it’s not my faith but it’s interesting seeing how that’s been reflected actually, or you know, refracted in some way within the book, the idea of sound and sort of nature of belief and how people are yeah, accessing this real meaning through sound in this case.

Jael Richardson 25:29

It’s so fascinating to me to hear you talk about those things, some of which are very familiar to me in terms of, you know, different faith, but same kind of like gathering together talking, singing praise and the ways in which that shaped a sense of community, a sense of belonging, and you see that happening for Claire, initially, kind of on her own, and then finding this, this community. And it was, I mean, I was really struck by a number of things in that regard. And one of the things I wanted to ask about on a craft level, as it relates to Claire, is that you’ve chosen to tell this story as a memoir, and I find it fascinating. It started as a play, it became a novel but not just a novel, a novel that’s written as nonfiction, as written as a memoir, a woman sort of giving an account of her life in this particular moment in her life. And was that, did that come naturally? Was that like the voice and the way the story just came out to you? Did you have to find your way into the way she was telling the story? Because memoir affords itself a particular, either you’re talking about the nature of truth, you’re talking about conspiracy, and then she’s telling it as though it is a true, true story, right? Like, did that come right away? Did that seem like the organic way to tell the story? Or did you, did you have to find your way into that style and structure?

Jordan Tannahill 26:45

Hmm, it’s yeah. It’s a great question. I became pretty quickly, and I think part of it was intuitive. Impart I think it’s relates to, you know, in theater, in playwriting I love a great monologue. I love a good monologue. You know, it’s so interesting to you know, have a character kind of, you know, hold that space, hold court and, and just give it. But the, monologue has to be powered by somebody. It has to have an engine and I think the question that a playwright always has to answer is, why does this character keep speaking? Like, what do they need from either the person they’re speaking to, which is another character or the audience? And in that question of why does this character keep speaking is like, so central to how a monologue functions. And I think in a sense, that The Listeners is a kind of a protracted monologue. It’s kind of a long, extended inner monologue of Claire’s, and which gives a great sort of intimacy to her and, you know, we get to really sort of, you know, we really get to feel her. The sort of inner machinations of her own kind of thought process and her own sort of, the ways in which, you know, reasons and logics are sort of, you know, reasons with herself, the logic of the hum and her relationship with it. But, and for me, the memoir as a form is kind of, felt like the most kind of candid way of kind of allowing her to have this extended monologue, to have this inner monologue. And for her to kind of speak in the first person, really. And I think that form, that structure was really, her voice was the clearest thing for me at the very beginning of this process. I think character voice is my way in, often to prose, I guess, again, as a playwright, so yeah, for me, it felt like the way to kind of have her tell her story in first person.

Jael Richardson 28:47

It’s funny when you say that you thought about it as monologue, I, one of the things that I love, I’ve always wanted to start a novel with like, the way the story ends. I’ve always wanted to be like, well, the story ends here but let me start back at the beginning. And I can never like, I have not yet been able to do it. It takes a particular kind of strength in a story and in a character to be able to start with the ending and keep the reader all the way through until they’re very satisfied with the ending. And, I mean, one of the things that I love about this book is that it does that. Starts at the beginning, starts at the ending, right with like, you’re gonna find me on the street like, well, you know, this story happens, it goes public, it goes viral, and then she’s gonna explain how we got there. And it’s so captivating to think about it now. I want to listen to it again, and read it again as thinking about a monologue because I think it’s really powerful in the way that Claire’s able to convey this particular story. Did you find any of, because I keep thinking back to this play that you’ve written and these 20 characters that were there and we’re giving voice. Were there any characters that were more difficult for you to write and create and did the play, or hearing the the play read out loud, performed out loud? help you navigate that character in the novel?

Jordan Tannahill 30:03

Hmm. I mean, this is maybe a cop out answer but I do think Claire, in a way is the hardest character to write in this book. I mean, I think it’s, it’s, you know, people always ask, well, you know, you’re a 30-year-old gay man, you know, like, what are you doing? Right? You know that this whole story, this whole novel in the voice of this, you know, 40 something year old woman. And in a way, I feel like Claire is certainly made in some ways, and also, she’s like, my best friend, Jennifer, she’s also you know, a lot of the close women in my life. And, yeah, it’s strange. I feel like, in a way, I feel like writing the voice of like, a heterosexual woman is, like, easier for me to get my head around than writing the voice of like a heterosexual man. Like, I actually literally, in a way where, I just think there’s way more of them in my life. And I just like, I associate with them in some of the other kind of profound ways. And I feel like, her sense of humor is my sense of humor, and also, that of, you know, my friend Jennifer’s. And I think, I don’t know, so I think that, and yet, and yet, you know, within a piece of writing as long as a novel, any sort of, you know, sort of moments that feel untrue, will really bring out you know, and like it could be just a line, it could just be a sentiment, can so easily ring false. And so I think that, that sort of requires immense amount of rigor, and, you know, rereading it and reading it aloud and saying, you know, can we, do we buy this as a real person, as you know, as a real mother, as a teacher, as a friend. Like, you know, does she feel like a three dimensional character, and so perfecting Claire’s voice and finding it was really the hardest thing.

Jael Richardson 31:45

One of the things, so we are going to open it up to questions in a little bit. So if you have questions, this is the moment to start crafting them in your mind and popping them in the q&a box so that when I get to that point, you don’t leave me hanging here. Like, what is next. So make sure you drop them in the q&a box. I have a few more questions before we get to them. But we are going to get to them. And I love to spend lots of time on audience questions. So make sure you do that. I want to talk about, I want to get to the ending. I may have skipped a lot of places in the middle but I want to talk about the ending. The first one of my questions is because I loved Claire so much, and because I loved the story so much and the character so much. I wonder, as someone who has cheated on my first novel, and then I’m writing a sequel so that I don’t have to like imagine, do you think about what happened to these characters after this story that you’ve written? So that’s sort of a question. And the other question I want to ask about that is, was this ending always the ending that you were going to land on? Was this sort of like you had that in mind? This is where it was gonna wrap up? This was like, what you were going to leave us with? And then do you think about the after?

Jordan Tannahill 32:57

Right. Yeah, yeah. And for those who maybe haven’t read it, I’m just gonna totally spoil it for you.

Jael Richardson 33:04

This is a spoiler. If you’re watching this and you haven’t read it, press pause. Well if you are watching it live, it’s too bad. If you’re, if you’re watching on demand, just pause it, read the book and come back. Okay, go.

Jordan Tannahill 33:14

Yeah, exactly, exactly, exactly. Um, you know, basically, after any, I’m not sure how much to give. I mean, at the very end, Claire, Claire, so after this, this kind of climactic, after the climax of the story, say, it’s quite a kind of tragic climax. There’s deaths, and we’re kind of led to, the source of the hum is found. It is attributed to a very kind of mundane, local white noise issue. It’s an industrial white noise issue, which is often the case with a lot of these localized clusters of, of the hum. Oftentimes, they are traced to a localized, you know, white noise problem. Like a blast furnace at a factory, you know, that’s causing vibrations or, you know, an electric substation that’s, you know, causing, you know, sort of charge in the line, that kind of stuff. So it, it can often be something very mundane. And likewise, a sort of mundane reasons is found for the source of the hum. And yeah, and so Claire does at some point, say, okay, maybe I don’t hear it anymore. And she kind of convinces herself really that she doesn’t hear it. And she tells her family that she doesn’t hear it and we begin to kind of get the sense that maybe she is going to kind of get over this and the family is going to reconstitute itself and, you know, build back a sense of love and trust. And then in the very sort of final pages of the book, Claire begins to hear the noise again, she gets into the home again. And the return of the hum for her, despite the fact that this local white noise issue has been addressed. You know, the return of the hum for her is both this kind of moment of terror, but also this moment of, of kind of ecstasy, because she realized that she still has this thing in her life which, which has actually imbued with immense meaning. You know, it has been a hugely destructive force. It has lost her her job, it has destroyed her marriage and basically caused you know, caused her to become kind of an outcast in her community. And yet, she’s also found a deep sense of connection with these individuals a sense of spirituality. And, yeah, so we’re kind of left with this kind of, sort of image of her on her staircases she’s walking up to, to go back to a room and change, where she’s kind of stopped and kind of realized that she can hear it once again, and she’s kind of just sort of laughing and crying and sort of just in this moment of suspension. And I knew that that moment, that’s that I guess, that kind of final tableau, I suppose, of Claire on the staircase, hearing that noise was how I wanted to end the story. And that sense of, of us questioning whether she has in fact, you know, invented this, not invented this, but has, whether this is a kind of localized mania, a kleptomania, that these people are kind of, you know, like, had kind of manifested for themselves. Whether it was just a kind of pedestrian white noise issue that she has been kind of, you know, fixated on and built into this whole thing. Or maybe it is a kind of supernatural or sort of geoscientific kind of wonder that she is able to tune into uniquely, that maybe a handful of people can, you know, we’re really left questioning whether any of these possibilities are true. And I think that’s really where we are with faith more generally. But also with this question of the hum. It remains an unsolved mystery. And so I think it’s something you know, I wanted to kind of leave the reader with that sense of both wondering and not knowing.

Jael Richardson 36:52

I love that. You know, as a theatre person, I like, I can picture, like the stage, the light that, you know, she’s pausing, and then we all hear the sound, and then it all goes black. You’re like, what?! I love that visual. The last thing I want to ask before I get to the audience questions is about what’s next. And in particular, what I, what I’m interested in is, in your first novel, you you started out kind of as a memoir, and then it became a novel, in the second one, it started out as theater, and then it became a novel. And so I’m interested in whether you are, well, how theater, like what’s happening in your theater plans as well. But on a novel level, are there more novels coming that you know of? Or do you think you’ll always kind of like, accidentally end up in novel territory? Do you know? Are you setting out intentionally to write novels now?

Jordan Tannahill 37:47

I am, yeah, I’m writing my third novel at the moment. And, and I’m, and it’s definitely kind of a larger kind of multi character, sort of, piece that kind of spans a sort of larger period of time, I’m, I’m really interested, I’m not sure if this is what it’ll ultimately be, I’m really interested in exploring the kind of the advent of AIDS within in Toronto and sort of the early 80s A whole period really from the the bathhouse raids in Toronto and the sort of the, the, the kind of birth of a kind of contemporary queer liberation movement. And yeah, the ensuing riots and, and how that kind of coincided with AIDS. And, I really feel like there’s such a kind of extraordinary kind of multi-character, multi-generational story to tell about that time. In, not just in Toronto, but you know, generally across our country, and, but following in kind of a cast of, you know, a kind of ensemble, it like a sort of, you know, a cast of characters who are kind of a chosen family over three generations. And so, I’m thinking about the moment. But I think, but it kind of links these these stories together. A kind of question around, faith and community and also the body, you know, the sort of, the body as a kind of, as a political side of questioning and of pleasure and also of atrophy and kind of terror. And but, but yeah, the body is a political subject. I’m really interested in a lot.

Jael Richardson 39:16

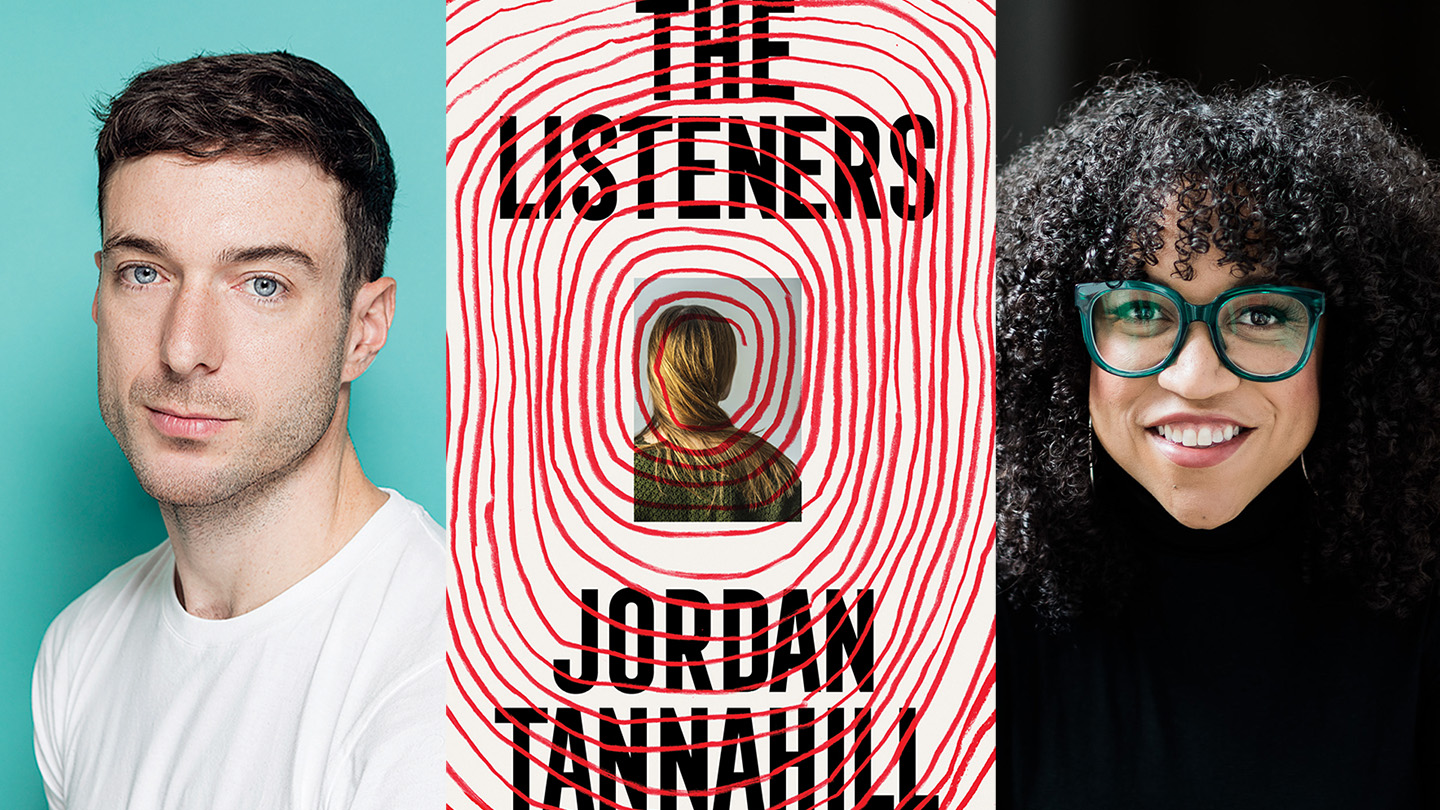

I love it. Big fan. Okay, so we have lots of questions so far in the question/answer box, that doesn’t preclude you from asking more. So, make sure, this is sort of like your final call for popping them in. I love this question from Kathy, which is the one right off the top because it’s something I always want to ask about. I’m just worried I already asked it in one of our other interviews and conversations. So here we go. I love book covers. I love talking about them. I love examining them. Can you tell us, so Kathy asked, can you tell us about the book cover. In particular the photo of the woman, but I’m saying like, tell us about it all. Like, how much did you weigh in on it? What did you think of it? What does it mean? All of it.

Jordan Tannahill 40:04

So this was an amazing cover by Jack Smyth who’s a UK designer. And it’s so rare that a book cover is offered on the very first outing to you and you’re like, yeah, that’s it. Like, this was the first draft, the first book cover. I like, I like, yeah, I’m like impossible to please when it comes to covers. And yet I was like the first, yeah, he sent that in. It was like the same, it’s the same cover on both sides of the Atlantic which is amazing.

Jael Richardson 40:39

That’s that’s rare to.

Jordan Tannahill 40:40

So rare I know. I feel like Sally Rooney or something. It’s so lovely. Because it’s like, it’s all HarperCollins which is so nice. And I was like, this has to be the cover, this has to be the one cover. And I think this kind of like thumbprint, spiral sound wave, kind of, this sort of multi-vaillant kind of, sort of hand drawn line design that he’s done is really beautiful, and kind of just yeah, it just works so well. It also can be kind of like, you know, a madness spiral like vertigo. So it’s sort of, yeah, it’s great. And the photograph, to be honest, I don’t know anything about who this person is or even the photographer. I think the photographer is probably in the in the inset, but Jack found that photograph. We looked at a few different other possibilities of other women. And, you know, they’re either kind of not quite the right age, or quite, you know, but yeah, I just found her. It was the first one that he suggested and I mean it just felt right. So, yeah.

Jael Richardson 41:34

I love that you can’t see your face. That’s like my big part. I love it. Like, all you get is his hair, which says a lot, but not a lot at the same time. It’s really, it’s really, it’s a great cover. It’s a great one. It’s one of the ones you keep, you can keep looking at. So this is kind of, you know, philosophical question. We’ve gotten philosophical. And so here’s another one. So in looking at this story, in looking at the world that we’ve lived in, there’s a lot that’s been happening, and it’s a it’s a lot right now. And the question that Riva has posted is whether you consider yourself optimistic or pessimistic about the world. And I want to I want to look specifically, as you’re talking about this book, were you approaching it from a place of optimism or pessimism or neither? Did it change as you’re working on the book?

Jordan Tannahill 42:29

Mm hmm.

Jael Richardson 42:31

Like, are you, do you normally consider yourself optimistic or pessimistic?

Jordan Tannahill 42:34

That’s so hard. I feel like I’m, I don’t know, this is such a kind of invasive answer, but I feel like, I guess like, terrible shit will always keep happening. You know, it’s like, I’ve kind of neither I’m kind of just like, you know, it’s like, we’re just always going to be in the cycle of, you know, there will always be kind of glimmers of beauty and hope and poetry and human kindness and there will also always be, you know, morally degraded creatures as well. You know, I think it’s sort of, you know, it serves for me, it serves most to be prepared. I think there’s this great Audrey Lorde quote, where it says, you know, the, something to the effect of issuing warnings about the future isn’t ultimately an act of hope. You know, I think like or, like trying to predict an issue warnings to future generations is ultimately an act of hope, even if those predictions and warnings are deeply pessimistic in nature. Even if you know, even if it’s to say, look, you’re going to encounter the absolute utmost horrors at the hands of other humans. Be prepared. The fact that we’re still taking the time and energy to warn others or write, you know, beautiful dystopian novels like Gutter Child, you know, that is an act of hope to say that we still believe it. You know, stories of retelling the warnings are worth issuing that children, you know, generations will still be alive to receive them, even if those warnings, even if those messages are deeply troubling. I think messages will always be deeply troubling, I think that’s sort of the nature of what it is to live with feelings, people on earth, in some kind of form of conflict, but I do find hope and I guess I do find sort of optimism, I suppose within acts of art making and community.

Jael Richardson 44:19

And I think in some ways The Listeners tends to me to be optimistic in that it gives multiple people voice. And I think when you give multiple people voice from different perspectives, people who might normally like disagree with heavily in real life or not, you know, there’s this sense of optimism I think in that because it allows us to see the humanity where we’re normally prone to see the kind of problems or troubles or faults in a person. I found it optimistic on that level. And I found that optimistic for Claire too. I think there’s this sense for me at the end that she, yeah, that the hum is a part of her and that hearing it again is actually, you know, an act of hope as well that like, this part of her, that she values is still there. You know? I may have killed that, but you know.

Jordan Tannahill 45:12

That’s it. I think, I think for me, I think that part of this book was reckoning with with how is the people are, you know, like, why do you… Why are people drawn to faith? Why are people drawn even to conspiracy culture, you know, or conspiracy theories. Things that I feel like can be very toxic or corrosive. You know, sort of forces in our, in our political or social sphere that also can be especially, particularly faith can also have deep beauty and meaning and….

Jael Richardson 45:54

Hopefully, we haven’t lost Jordan. Jordan, if you can hear me, you’re a bit frozen. So I will, there’s a couple of really great questions in here. So while we’re finding our way back to you, um, one of the things that I thought was really interesting, and Elizabeth, you freaked me out with this question a little bit. But there’s a question about whether Jordan heard the hum while, or did a hum like sound sort of haunt him while he was reading. And, while he was writing it, and I wondered for many of you, maybe you sort of felt like that. I feel like sometimes when I read conspiracy theory books, I’m like, am I hearing something? Ss that, even as he was talking about it today, I was like, do I hear a hum, consistently? Is that my fridge? So I thought that was really interesting that he brought that up. One of the things I’m going to ask him about if he’s able to log back in, there’s a great question about Kyle, we’ve talked a lot about Claire, and Claire’s role in the story, because obviously, she’s this main character. But I do want to ask this question about Kyle, when he comes back. And there’s a couple questions about Kyle. So keep putting the questions in, we’ll see if Jordan is able to join us for the last five to 10 minutes. If not, I will find a way to just casually wrap this conversation up. You can also ask me questions about the Giller or about interviewing the Gill authors, and I’ll be happy to answer them. I’ll tell you a little bit about some of my favourite Giller moments such as this year, but also the things that I’ve learned about the Giller. This year was pretty cool, because we got to meet in person for the first time. But usually, we actually, the author’s go on tour across the country, and I get to interview them in one or two cities. And then they’re in Toronto with somebody else. And so this is my first time actually doing the Giller conversation in Toronto, with all five of the authors and that was really fun. And then we also got to go to, of course, the awards night was was in person again this year. And that was really great. And so some of the things that we do, I think Jordan is back. Yay! Jordan, welcome back. I was just telling them about interviewing you in Toronto. So I was just filling in some time, because we do have some really great questions. One of the questions is about whether, did you hear a hum? Or did you like, find yourself getting a little bit like in the zone so much that you started to hear something? Like did you ever worry about that?

Jordan Tannahill 48:25

Well, I when I was writing the book, initially, I was living in this basement apartment right by the City Airport in London. And I could hear this like, kind of like low grade roar all day long from planes taking off and landing. It was just this kind of like, yeah, this is kind of atmospheric din and that, that definitely informed my writing. Like, it was a sound that I could almost kind of feel physically at times and it was like, a pretty shitty apartment. And so I think I really tuned into what it was to live with, yeah, to live with a sound that you couldn’t really escape day in, day out. And then I really did kind of empathize with Claire’s. I only lived there for about a year. But that was the very first year I was working on that novel. And it was really informing. Yeah, how I kind of approached writing Claire. I don’t actually hear the hum. Which is you know, like this this specific kind of low frequency hum that people do report hearing. Although it’s amazing that since writing the book, I’ve had so many different messages, emails, basic messages, people who do hear the hum. And it’s yeah, it’s quite, it’s quite sobering, some of the stories people have been living with it for sometimes years.

Jael Richardson 49:53

So one of the questions that was asked in a couple of different ways is about Kyle, and I’m gonna roll back to the first one because it had a couple of layers. And one of the questions was about how rich Kyle is as a character in and of himself. And so the question is, how did you decide he should enter the narrative? And when did you decide about his conclusion in the story?

Jordan Tannahill 50:21

Yeah, yeah, thank you. It’s the very, so when the seed of the idea initially presented itself it was at, it was a relationship between a teacher and a student. But from really, from the very kind of first inception of the idea, I just thought about this fairly new teacher, maybe in her early 40s, who starts to hear this noise, it begins to kind of distance her from her husband and create this kind of strain in her marriage. And she finds solace and the sort of unlikely friendship, unlikely intimacy with a student of hers, who is perhaps a little bit of, you know, sort of precocious little bit wise, beyond his years. And there should be this kind of sweet genre’s nature to this relationship, but it’s a bit, you know, it’s not sexual. It’s never it’s never consummated relationship. But there is this kind of attraction that is perhaps inappropriate, but is founded in the sense of her being listened to, her being heard, when she’s not being listened to, or heard, really, in that kind of profound way by anyone else in her life. And so yeah, from the very, very beginning, I really kind of, Kyle was kind of one of the key factors in this whole kind of narrative. And actually, initially, in the play when I wrote it, he didn’t die. For those who haven’t read it sorry, Kylel does die in this relationship, this person, this person, she has this relationship with, her student. Kyle does die in sort of the climax of the novel. Initially, he didn’t actually. Initially in the in the play version, it was, it was actually Joe, and this character, Damien, who die and that was dramatic in its own way, but actually, when I kind of began working on the novel, and kind of reimagining everything and kind of starting from scratch, by the time I got to the end, I thought, of course, of course, it has to be Kyle. Of course, you know, she has to in a sense lose everything. And still, even, even though the hum has taken everything from her, including Kyle, including this person who she kind of really loves. She still chooses or chooses or allows herself to hear it at the end. She still hears the hum even after Kyle is taken from her. And in a way actually, her hearing the hum is the way that she kind of keeps him in his. in her life. Like Kyle becomes kind of present for her or remains present for her through her hearing the hum. And so yeah, it just kind of, for me, it just felt like it really kind of brought, it was the it was the emotional linchpin at the end that needed to happen to kind of just kind of tie it together I guess.

Jael Richardson 52:53

One of the questions we had talked about was about how difficult writing Claire was, and how the kind of challenge of like getting in there. And I guess this is more of like a tactical slash practical writing question is, how did you overcome that? Did you have like, different strategies you use to navigate the challenge of writing Claire? And what was it along the way that helped you, you know, feel, not just write it well, but to feel confident that what you’ve written was was full?

Jordan Tannahill 53:20

Hmm. I think I’m just having like lots of conversations, or conversations with, you know the couple of friends who I feel like I was really inspired, you know who Claire felt really inspired by and just really pay attention to how we speak, how they express themselves, how I express my thoughts, and kind of, in a way, sort of allowing myself to also be a foil for Claire.

Jael Richardson 53:44

Can I ask you about that?

Jordan Tannahill 53:45

You know, really allowed what she’s saying so that, you know, it just you know, how…

Jael Richardson 53:50

Yeah, no, no, no, sorry. Sorry to interrupt, because I know there’s a bit of a delay. I was going to ask when you were talking to those friends who kind of inspired her, did you, did you talk to them about conspiracies as well? Like, was it, did you get on kind of topic to hear how they would talk about those things?

Jordan Tannahill 54:06

That’s interesting. No, I didn’t so much get into that. But that’s a great point, though. I mean, I did read a lot about conspiracy and not just about conspiracies. I read people expressing themselves about conspiracy theories. So reading, you know, reading threads, you know, in chat forums, you know, you know, going into like the 4chan, 8chan, Reddit, understanding how people this, you know, not just talking about, you know, conspiracy theories. Talking about faith, how they talk about, yeah, how they talk about belief, you know, and the formulation of kind of confirmed bias too, you know. The ways in which a kind of echo chamber can be kind of established within a kind of episteme or, you know, a kind of small community of people who believe the same thing. So really interested in the ways in which also kind of new age language has been kind of adopted to kind of talk about the hum and sort of the frequencies. You know that this idea of the earth, the earth frequency, the Mother Earth frequency, and the ways in which like language or vocabularies of care, and, you know, self care can sometimes be also kind of co-opted and used within, within, you know, conspiracy culture and stuff or faith. So I’m just interested in the ways in which we kind of, yeah, you, the ways in which people talk about faith and idea. And yeah, anyway, so I just read a lot about, or read a lot of people’s kind of threads and posts about that and that felt really, you know, kind of facinating, endlessly fascinating. I’m really interested in kind of those like nether regions of internet. Yeah.

Jael Richardson 55:43

I am not. Just so you know, and I find it fascinating. I’ve probably listened to what I believe to be more conspiracy theories or wild ideas in the last two years than I ever felt I listened to before. Yeah, and I have felt overwhelmed by like, people really think this way? l found myself multiple times. So I find it fascinating that you were able to like delve in there and sit in those spaces. But I also see like that, I also recognize that the value of that first person. Right? Hearing people deliver it in their own voice is so helpful to a playwright, and to a novelist, I think. To hear that, the actual sound of people’s words in order, in the way that they’re expressing something. The last question I want to ask is, like a true, you know, craft process type question. And, I think it’s a great way to kind of wrap up as we’re thinking about you working on this next project. What are kind of your habits or the way that you practically approach writing a novel? Is there something you’ve done? Does it change with each book, depending on what it is? Or do you have sort of like a methodology or rhythm about how the novel evolves from idea to the finished product?

Jordan Tannahill 57:02

Yeah, um, I, I sort of, you know, I mean, this, I’m not sure you know, who coined this idea, or where it comes from. The idea of kind of start in the middle, just like kind of start writing the juiciest stuff first, I guess. And I think that’s kind of it for me. Like I think, initially when, I think the idea of sitting down and writing a novel is like, such a kind of overwhelming task, or kind of, I think we can kind of psych ourselves out and kind of like, begin writing the first chapter over and over and over again, and we will never kind of get beyond the first chapter if we’re, if we’re trying to kind of trying to write a kind of masterpiece from beginning to end and imagining this kind of, you know, sequential process of, you know, just putting that one paragraph after the next. I think, for me, I just kind of need to dive in and begin kind of, it’s like, just wrestling with it, like it’s sort of just jump into the fray. And so yeah, begin working on a, you know, on a love scene or on, you know, someone’s deathbed. Or just like, the stuff that you can already see in your mind that feels vivid and clear and dramatic, write that first and then begin to build out from there. And that’s kind of how I’ve been working mostly is just kind of, even with plays as well I kind of sometimes write the climax first or write you know, write this kind of, you know, ultimate ending scene and then kind of work from there and kind of piece it together from that. So I, yeah, I don’t write chronologically, and I find it seems challenging to a little bit more with The Listeners I did but I did kind of begin with some of these kind of more, I guess showpiece scenes and kind of built up from there, I guess.

Jael Richardson 58:51

I have never, I’ve asked that question a number of times. I’ve never heard that answer. And I now, I’m like, troubled if I’m doing it all wrong. No, I’m just kidding. But no, I think it’s really great to think about well, I think I do something similar in that my first draft is always beginning to end so it does work chronologically but it’s all the big parts all the good stuff like, the first scene that I can imagine the next scene the next scene and I skip all the like, how they got there or all like logistics of how it happened, which gets me into trouble. But yeah, I think it’s it’s similar, but I love the idea. I can’t imagine starting at the middle or starting at the end. Like, I feel like that’s, that’s just my a type personality cannot handle that. But I like the idea. I’m going to leave it with you for that.

Jordan Tannahill 59:36

I’m like yeah, like I see sometimes people with you know, like 200 sticky notes across their whole, you know, bedroom wall or their office wall and it’s all charted out and I think wow, that’s so fascinating. Your mind works that way. But it’s like not how my mind works at all. Like I’m just way more sloppy. Like I don’t, I also don’t, I chart nothing out. It’s just, it’s just kind of, it’s in here until it’s on the page. And I don’t know and I kind of just work from there. It’s a very it’s a very kind of just, yeah.

Jael Richardson 1:00:03

I mean, we’re not throwing any shade at Omar El Akkad. Not at all. I mean, none.

Jordan Tannahill 1:00:07

Oh yeah, that’s true. Wow, that is completely facinating.

Jael Richardson 1:00:11

When they showed that video at the Giller I was like, oh my gosh. That is impressive. We love Omar, I love Omar and I say that quite openly so it’s fine.

Jordan Tannahill 1:00:22

Incredible. Yeah. No, it’s amazing.

Jael Richardson 1:00:24<

Alright, well, I think Daphna is going to come in and give it a wrap. But Jordan, I, again, I miss your outfit. I miss your face in person. But it’s really great to be able to talk with you and to be able to chat with you.

Jordan Tannahill 1:00:38

I always love chatting with you. It’s so fun, Jael. Thank you so much. And thank you for those great questions, everyone. I’m sorry for the terrible bandwidth. But thank you for sticking with it. I really do appreciate it.

Daphna Rabinovitch 1:00:48

Well, thank you both so much for joining us this evening. It was just wonderful despite we missed your face for just a few seconds. But thank you Jael for asking such probing questions, and Jordan for giving us such definitive and sensitive and generous answers. And thank you all for joining us tonight. And for also all of your questions it was sort of like a banner night for for audience questions. This interview will be available on our YouTube channel during the next few days. And please don’t forget to join us on March 21, when Catherine Hernandez will be interviewing Katherena Vermette, author of The strangers which was longlisted for the 2021 Scotiabank Giller Prize. I look forward to seeing you then. Thanks so much. Goodnight.

Share this article

Follow us

Important Dates

- Submission Deadline 1:

February 14, 2025 - Submission Deadline 2:

April 17, 2025 - Submission Deadline 3:

June 20, 2025 - Submission Deadline 4:

August 15, 2025 - Longlist Announcement:

September 15, 2025 - Shortlist Announcement:

October 6, 2025 - Winner Announcement:

November 17, 2025